Here is my video and discussion of sources regarding Temilotzin of Tlatelolco. If you're the type that gets excited about bibliographies, the scroll down below the video to see what sources I used to make it. If you're the type that isn't excited about bibliographies, I pity you. Now, onward!

Temilotzin of Tlatelolco was one of the first historical figures I tried to make a fifteen-minute show on. I was working at a job where the most difficult activity each day was emptying out the mailbags, and so I had a lot of free-time on my hands. I had a copy of Miguel Leon-Portilla's Fifteen Poets of the Aztec World and all the incentive in the world to read it.

But it was another thing to try to distill what I'd read from that source into a quarter of an hour. I retyped Temilotzin's poem in English, and tried to fit it into about a 1500 word essay on the end of the world and trauma.

It was my first go at historical storytelling, now that I think about it. I took this essay on Temilotzin to the open mics I frequented and tried to do what I had always done at open mics: read words I'd written before, and hope to the various gods I'd structured it properly and that the audience could follow my meanderings.

I choked up when I had to read quotations from Temilotzin's work. The words, even translated into my native language, to me, still have enormous weight when spoken aloud and contrasted with Temilotzin's ugly fate.

The open mic audience was polite, I stared at the page and didn't make eye-contact with the people I was meant to be entertaining, and rushed through my reading.

Rookie mistakes.

But while my performance was shaky, Temilotzin hasn't left my mind in the three years since then. Part of the horror I feel when storytelling is all the things that one is forced to leave out for the sake of structure, and so as not to distract the audience with too many names or dates. There is always that temptation to dig too far back in time and lose sight of your original goal.

Temilotzin of Tlatelolco has a special place in my heart. I've learned a lot since I first began performing (like ditching papers when presenting, learning how to tie hand gestures to memory etc.), but I've always wanted to try and tell Temilotzin's story again. One of the troubles with history is that providing context can eat up all your time, before you even get to the person you want to discuss.

But I'd never get anywhere if I didn't try, so after about three years, I looked over my notes, wrote up an outline, and then decided to try again. I had more sources, more context, and the same amount of time.

So let us begin. The sources for this story.

1. The Anales de Tlatelolco (date of publication unclear, some say 1527, more likely 1540s).

The Anales de Tlatelolco is a fascinating work. It is possibly one of the oldest accounts of the Conquest of Mexico, though it's scope goes far beyond that.

Unlike the Florentine Codex--which also used the European style-text--the Anales remained in native hands and wasn't subject to Spanish scrutiny. This lends it several advantages over other sources, as well as making it a bit of a rarity, historiographically. As Camilla Townsend remarked in her book, Fifth Sun:

"[The Anales de Tlatelolco was probably the first set of Nahuatl annals to be recorded in the Roman alphabet...a great deal of circumstantial evidence puts the creation of the text in the 1540s. It was clearly authored by students at the Franciscan school in Tlatelolco, or perhaps by other Tlatelolcan who were taught to write by them...it contains highly traditional language and material and also reveals close knowledge of Spanish concepts and objects (the Spanish term "espada" is used to refer to a sword, for instance)".

Temilotzin, the warrior-poet hailed from this famous merchant-city, and it is from this source that we have the majority of direct references to him, including his dramatic death. It has been translated by multiple authors into other languages, most notably Miguel Leon Portilla as part of his work, The Broken Spears. It is an incredibly valuable document as close to a primary source as we have from the Mexica perspective regarding the conquest of Mexico and their history prior to that that remained out of European hands.

2. Bernadino de Sahagun (and a metric ton of native scribes), The Florentine Codex.

This remarkable work was written relatively shortly after the Conquest, in the 1560s and is widely considered the first foray into the field of anthropology. Written in Spanish and Nahuatl, the work is divided up into 12 sections, starting the origins of the Mexica pantheon and ending with the Conquest of Mexico. In between these are such subjects as the plants and animals of the new worlds,

Of course, Sahagun tried to gain a deeper understanding of the Mexica culture, language and thought process than many of his peers with the hope of both (in his mind) improving their lives and converting them to Christianity. This was in stark contrast to some other clergy and people of power in the New World, who participated and encouraged the burning of native people, holy books, sacred objects and temples.

Sahagun may have been enlightened for his time, but that didn't stop him from interfering in the history of the Conquest of Mexico to fit political expediencies. He inserted several laudatory passages regarding Cortes and the Europeans into the history, preventing it from being a purely Mexica text. It is a vitally important work--but don't expect to speed through it, it's a long and detailed read that demands your full attention.

3. Miguel Leon-Portilla, Fifteen Poets of the Aztec World, The Broken Spears, Aztec Thought and Culture.

You're going to be seeing the name Miguel Leon-Portilla a lot in this document. There is a reason for that. The man is a tireless translator of Nahuatl and helped open up a lot of documents for study that would have remained locked behind a language barrier beginning in the 1960s.

Fifteen Poets of the Aztec World in particular goes into some depth on Temilotzin's life and reputation as a poet and warrior, and is an invaluable source on his poetic style and shape of his life. The work contains true translations of the song-poems, first in Nahuatl, then in English.

Portilla's The Broken Spears paints a graphic picture of the sack and razing of Tenochtitlan using Mexica poetry and quotations from the Anales de Tlatelolco. It is a hauntingly beautiful work that underscores how much was lost with the Mexica empire--to the Spanish destruction of the aqueducts that kept the city supplied with fresh water (and were never repaired) and the cannibalizing of Tenochtitlan into Mexico City. The poem quoted in the title reads:

"Broken spears lie in the roads

we have torn our hair in our grief.

The houses are roofless now,

and their walls are red with blood.

Worms are swarming in the streets and plazas

and the walls are splattered with gore

the water has turned red, as if it were dyed,

and when we drink it,

it has the taste of brine

We have pounded our hands in despair

against the adobe walls

for our inheritance, our city, is lost and dead.

The shields of our warriors were its defense,

but they could not save it.

We have chewed dry twigs and salt grasses

we have filled our mouths with dust and bits of adobe;

we have eaten lizards, rats and worms..."

Lastly, Portilla's Aztec Thought and Culture is a deep dive into the Mexica Imperial-era culture. He covers how the nobility would have considered themselves, the structure of home-life, and philosophy, to name but a few things. He mentions, in particular, the free public education that the Mexica Empire mandated, even the children of slaves, something unknown in Europe at this time, in calpulli.

4.Inga Clendinnen, The Cost of Courage in Aztec Society and Other Essays

Clendinnen is one of my favorite authors on the subject of Mesoamerica. She writes with verve and style. On the difficulties of a Mexica warrior finding a well matched opponent in combat, she writes:

"Given the preferred form of combat was the duel with a matched opponent, locating an appropriate antagonist in an ordinary battle could be a vexing affair, especially for the more elevated ranks, which suggests the utility of the banners and head-dresses floating above the swirl of battle. The great warrior's best protection against being molested by trivial and over-ambitious opponents was the terror inspired by the ferocity of his glance, the grandeur of his reputation, and the fact that every warrior wore his war record inscribed in his regalia."

In her title essay, 'The Cost Of Courage in Aztec Society', Clendinnen examines the social aspects of Mexica warrior culture. Combat was a deeply personal affair, and one of the few ways someone could advance from the bottom of the rigid Mexica social hierarchy to the top, though even this was rare. Combat was largely melee, though the Mexica could and did use spear-throwers (atatl), bows and slings as projectile weapons to thin out enemy ranks.

For the average imperial Mexica warrior military service was compulsory, but only when war was in season--the rest of the time he was a farmer or merchant or what have you. Combat was not viewed as a team-effort, more as a loose gathering of one-on-one fights, with the goal to cripple or restrain your foe (optimally) with the goal of taking him hostage for sacrifice in Tenochtitlan. Naturally this was not always possible, and the Mexica had no qualms about killing on the battlefield.

Clendinnen writes that the Mexica warriors had a particular love of ambushes and shock tactics that worked very well in broken terrain against the Spanish in the ugly street-to-street fighting of Tenochtitlan, but less well on an open plain where the Spanish could deploy their cavalry.

An interesting thing to consider as I read this book was how Temilotzin's poem praised the power of friendship and conciliation with his peers, which is all the more remarkable given how on the traditional Mexica battlefield, fellow warriors weren't looked at necessarily as allies, but as competitors for captives.

5.Camilla Townsend, Fifth Sun

Townsend is also the author of Malintzin's Choice an excellent biography of Cortes's translator during the Conquest and after. She brings all her powers of study to bear in a marvelously researched history of the Mexica, from their perspective. Includes a handy in-text pronunciation guide for Nahuatl names and vocabulary, an excellent use of source material including the Anales de Tlatelolco, and further insights into incidents described by Miguel Leon-Portilla, such as the volcanic temperament of Tlatoani Axayacatl (Nahuatl: 'Water-Mask' or 'Face of Water') who outright conquered the trading city of Tlatelolco (Temilotzin's hometown a generation later) and brought it into the empire proper.

6. Ross Hassig, Mesoamerican Warfare and The Immolation of Hernan Cortes 1521, Tenochtitlan ( from What If: History as It Might Have Been Anthology)

Hassig literally wrote the book on understanding the logistics, tactics and realities of Mesoamerican warfare before and during the Conquest. While Hassig spends a considerable amount of time analyzing Mexica weaponry and tactics, this is as much a history of the evolution of Mexica warfare as anything. He takes the broader view of warfare, rather than Clendinnen's granular and personal one.

Hassig also wrote an excellent alternate history essay on what would have happened if Cortes had been captured (as he nearly was, suffering bad injuries in the process) during the siege of Tenochtitlan. Long story short, the Conquest would not have happened, the Tlaxcalans would likely have abandoned the siege with what they could carry, and the Mexica recovered and re-unified. The Spanish would be unlikely to get such a good chance to disrupt the Mexica again in the near future--they had other problems. End result, according to Hassig: a consolidated Mexica empire (or successor state made up of unified atlpetls) that would be able to resist Spanish incursion for the next fifty years and wildly change the balance of power in the New World.

7. Bernal Diaz de Castillo, True History of the Conquest of Mexico

Written by a former conquistador decades after the Conquest of Mexico, this is a valuable source and as close to an honest account as we're likely to get of the Conquest from the European POV. We do have Cortes's letters back to Spain to convince the king that he definitely is acting in Spain's best interest, yessir, no way was he defying orders, but those are self-justifying political documents (and leave out vast amounts of the narrative, like the presence of his native translator, Malintzin). They are a LONG way from unhelpful, but they don't provide the whole story.

Bernal Diaz is an invaluable resource because while he absolutely has an agenda by writing this when he did (an old man in his dotage desperately trying not to leave his family destitute, so he penned his recollections of the Conquest), he also didn't hesitate to deflate the legends from that era that glorified Cortes and minimized native involvement in the process of defeating the Mexica. He particularly had a loathing for historians who were willing to take Cortes's word at face-value, or wildly inflate the numbers of Mexica warriors who opposed the Conquest, like Gomara, writing in the introduction to his work:

Or, to put it in the words of Arthur Howden Smith:

"Gomara's history evidently was the last straw to Bernal Diaz who had nursed a very human resentment against the prevailing idea that the Conquest was the work of Cortes alone, the product of a superman's genius, although, apart from this, he retained for his old general an unblemished affection and admiration."

Never let it be said that spite never yielded positive results, scholarship-wise. Gomara's toadying directly inspired one of our best first-hand sources for the Conquest to write a refutation of his inflated and mythologized history.

Long story short, Bernal Diaz de Castillo will tell you the events of the Conquest as best he can remember them, and generally being brutally honest about what the conquistadors priorities were motivated by: lust for gold, for women, and for empire. Bernal Diaz doesn't sugar-coat it or try to justify his actions, save for in religious language, relaying the bloody history of the Conquest with a reporter's eye.

Another thing he is absolutely steadfast in reiterating over and over in the text is the crucial nature of native support for the Spanish enterprise, specifically the Tlaxcalteca (people of the city-state of Tlaxcala, the Mexica's traditional enemies). He says (pointedly) that without the Tlaxcalans and Malintzin, their translator, the expedition would have failed at multiple points, and points a finger at historians who neglect these facts. Speaking of the Tlaxcalans...

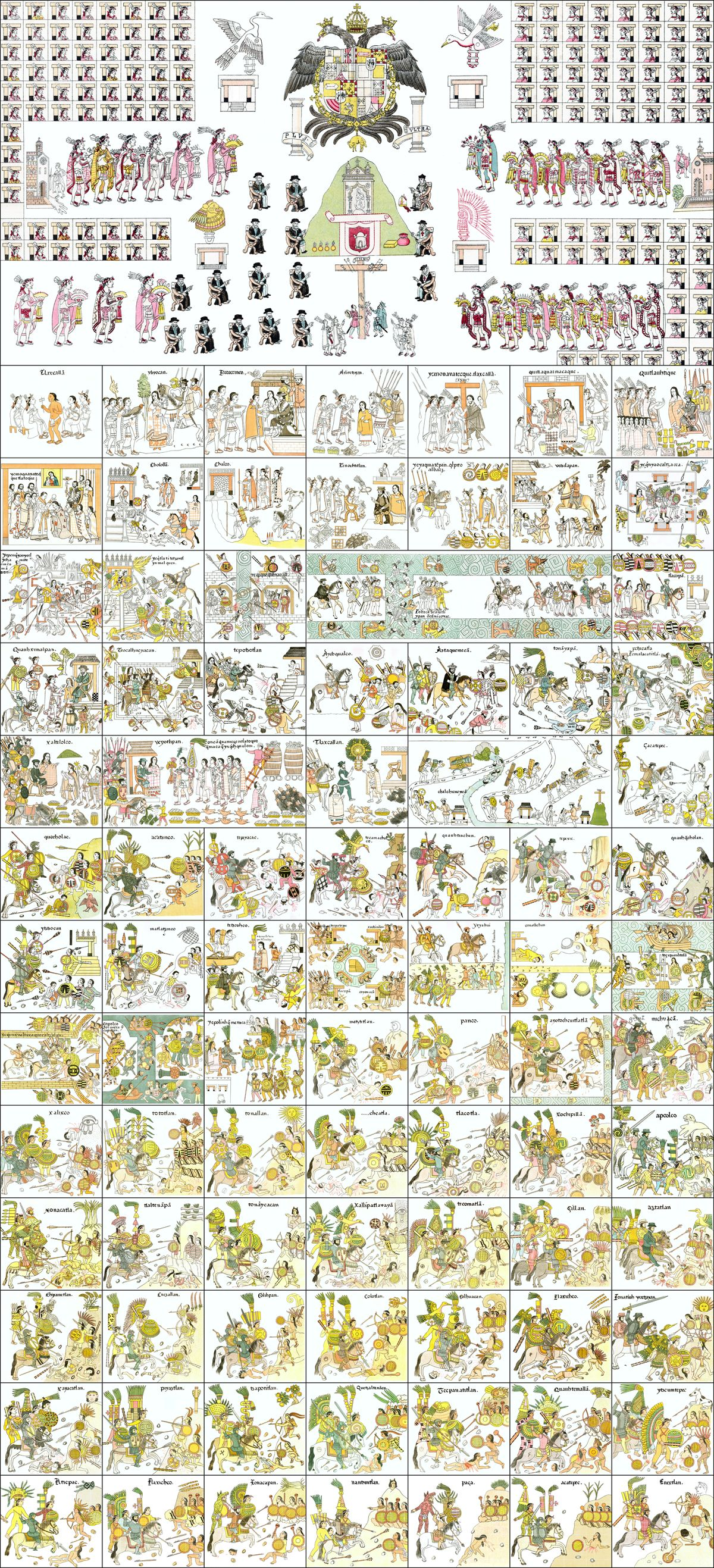

9. Lienza de Tlaxcala (various authors)

The Lienza de Tlaxcala is a hybrid of native and European art-styles. It is a history of the Conquest from the Tlaxcalan point of view, done in the native style of pictograms, but labelled with European alphabetics. This emphasizes the importance of native allies in bringing down first the Mexica empire, then the only other unified empire in Mesoamerica, the Purepecha of what is now Michoacan, Mexico and countless other atlpetl (Nahuatl: literally, 'water-hill', used to mean 'city') on the way. It is a reminder that the Conquest didn't end after Tenochtitlan fell: the deaths of the people of Mexico under the encomienda system, the plagues and the brutal crushing of dissent even among old allies.

These are some of the sources I used to inform my understanding of Temilotzin of Tlatelolco in the video above.

Still have more questions? Maybe someone asked a similar one at my live Q&A with Sewer-Rats Productions!

World History With Charlie Q & AWorld History With Charlie Q & A!

Posted by Sewer Rats Productions on Thursday, June 25, 2020