It is hard to get ducks in a row. My sister and I learned that when we were young. When my great-aunt and uncle wanted us out of their hair, they would give us a loaf of frozen bread and make loud noises about how hungry the ducks in the nearby river doubtless were.

Oaklyn New Jersey wasn't a difficult place to find your way around in: all spreading canopies of deciduous trees and uneven sidewalks set in geometric patterns.

Still, when my sister and I fed the ducks that would quack and clamber from the river a few blocks away, they never got straight in a row. That sort of grace and elegance was reserved for their in-water maneuverings or aerial displays. On dry land, there was bread to be had, and children's shins to nibble at, so composure could go hang.The ducks would go from a straight line to a gaggle, then to a cacophony.

To this day, I have yet to understand the phrase "Get your ducks in a row."

I mean, I get the meaning, but things, even when perfectly arranged, seldom come out easily. This is especially true with family associations and history.

It is natural that we tell the stories and histories that touch us, even in a glancing matter. History is by its nature, an associative, even emotional discipline. Often we tell stories that people we know lived through, or had a hand in, or were in the blast-radius of. They can feel more real.

My great aunt was a witness and tangentially involved with the underworld figure and rejected Monty-Python sketch character, Felix Bocchicchio.

This was a man with a long and, um, enterprising view of crime that would go more or less his whole life. From his un-redacted FBI file:

CRIMINAL HISTORY: FBI #3599540, Camden PD # 5577; arrests since 1925 including larceny, murder suspect, holdup, white slave traffic act, escape and breaking prison, assault and battery, state liquor violations.

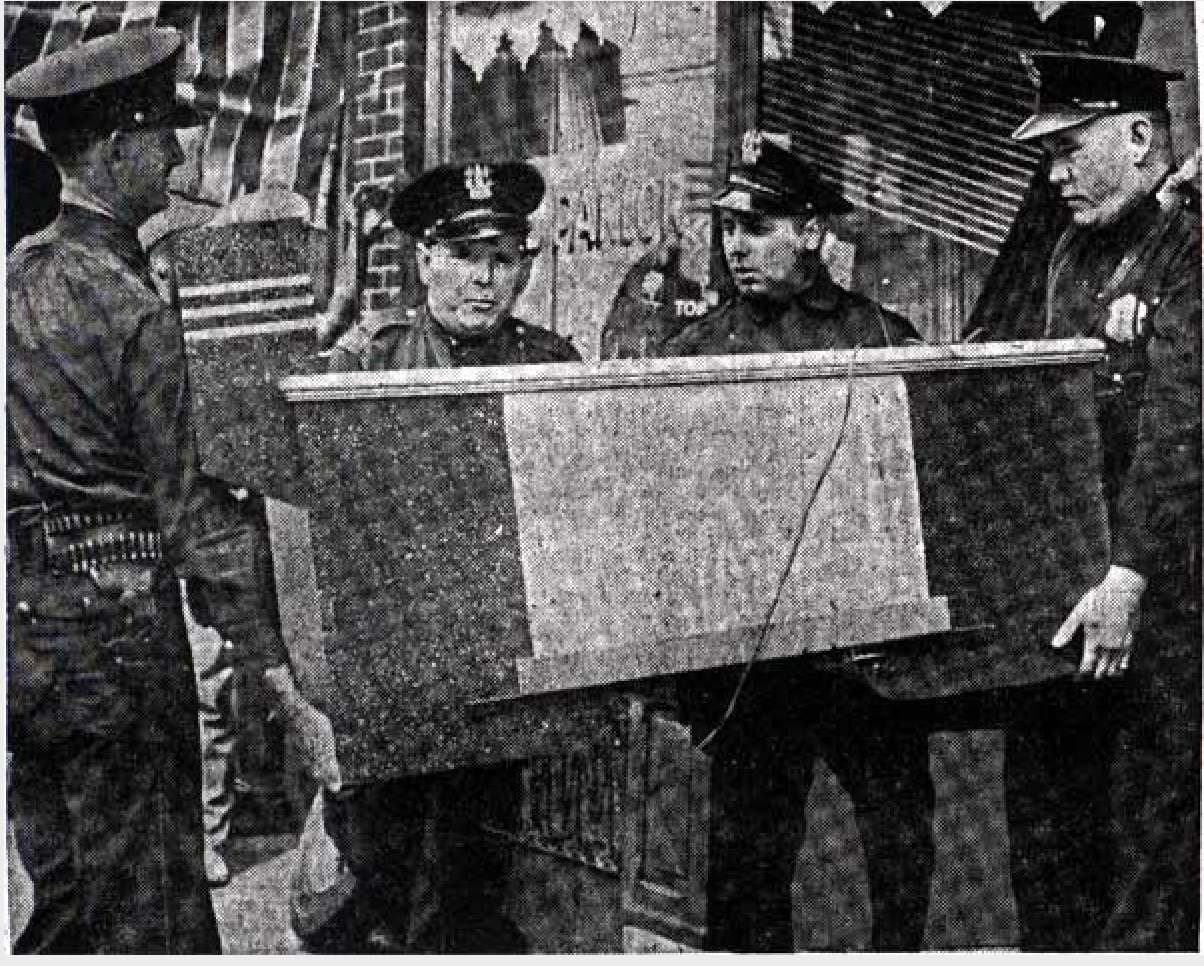

I'm shocked that pug-smuggling and loitering weren't included in this rap-sheet, given that in 1936 Bocchicchio was arrested and put on trial for dealing in the then-forbidden tech of pinball machines. It seemed as if both large crimes like murder of a police detective and stickups were embraced with as much gusto as small hustles like pinball machines and short grifts.

In my safely removed view of him, Felix Bocchicchio will always remain a weirdly comedic figure, even though he was a prime suspect and accomplice in the murder of police detective Feitz in 1934 and multiple stickups ranging from Lancaster to South Jersey ranging back to 1925.

My great-aunt ran the day-to-day and the books of Felix Bocchicchio's hotel in Mt. Ephraim, New Jersey. My blunt, direct-unto-death great-aunt who never met a point she didn't take as directly possible seems like the least likely person to run a mafia front-joint. But that was the way of things for her years of work under Felix, running a largely legitimate business.

"Felix was a man who did everything with his eyes," my great-aunt remembers. "Never said a thing." In her nineties, and fortunately as-yet untouched by the Covid outbreak, my great-aunt's eyes are clear as she recalls her early life in the shade of a tent outside her retirement home. She's uncomfortable with her own pale mask she needs to wear in order to see me in person, and I often in the course of the interview tap my own. Grudgingly, she would adjust her mask.

But, ungrudgingly, with an enthusiasm, she would discuss how her boss would do business decades ago.

She recalls Felix, when he bothered to show up at the Bo-Bet Motel, would come in at ten thirty on the dot and leave promptly at eleven-thirty. That hour was apparently enough to do whatever needed doing there. My aunt wisely concluded that Felix could keep whatever hours he wanted, he signed her paychecks, and besides she didn't want or need to know anything more. Anyway.

To my great aunt, tardiness is a self-evident sin on the scale of murder or theft. Had my great-aunt been carving the ten commandments, she would have made room for an eleventh: "Thou shalt never, ever be late, or thou shalt get what's coming to you."

So for her to be late to managing the Bo-Bet Motel, and two days in a row no less, was nothing short of mortifying to her, especially so early on in her career. The two way traffic of the Black Horse Pike was simply too much for my aunt on foot, never the most agile of characters. She was stuck in the unenviable position of being just outside her place of work, but unable to enter.

This did not escape the notice of Felix "Man-o-War/10:30-11:30" Bocchicchio.

My great-aunt didn't mince words then (or since) and explained the problem.

Inside of a week, with one quick trip to Camden City hall by Felix, there were two new traffic lights on the Black Horse Pike. One before the Bo-Bet Motel, and one directly in front of it. Problem solved, with the patented New Jersey mafia cocktail of blatant corruption, personal inconvenience, and some handy infrastructure in the bargain.

"Of course, that was how it was done." My great-aunt concluded. "It was crooked, but it got things done. Not like today." She gestured around the retirement home. "Someone is making money off of all this," she continued. "They're just crooks without guns." This conclusion was said in the tone of a professional who had worked for a significant crook with a penchant for violence.

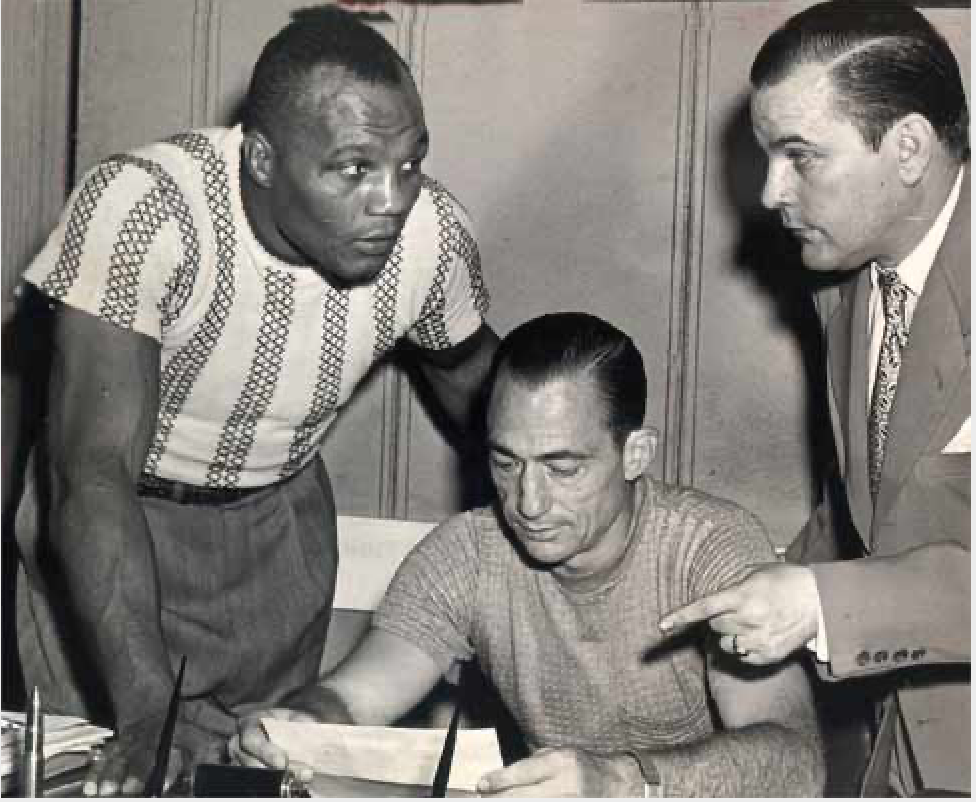

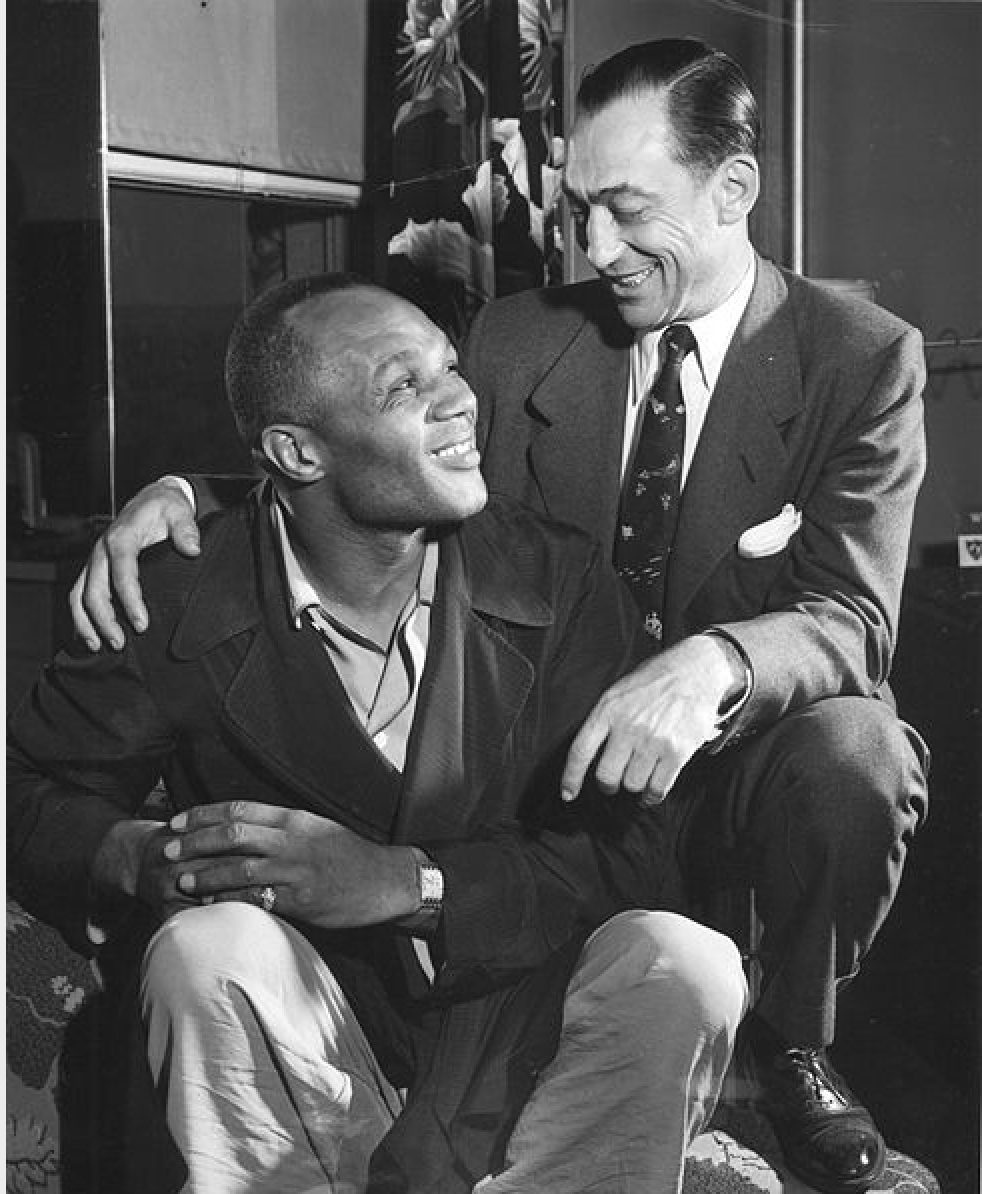

But if that had been all there was to Felix Bocchcchio, a murder suspect and minor mafia figure with a taste for games, he wouldn't have been interesting to me. Bocchicchio was at one point the manager of the world heavy weight champion of the world, Jersey Joe Walcott.

Bocchcchio's intuition about the potential of the down and out fighter in his thirties, with a family to support, proved correct. Some sources I've read state that Bocchicchio was moved by Walcott's poverty, which reminded him of his childhood, and drove him to take a gamble. I'm not sure what the ratio of constant risk-seeking behavior to altruism was with Felix Bocchicchio, but it scarcely mattered. He paid off Walcott's debts, got him a first-rate boxing trainer and helped Walcott swiftly rose through the ranks, defeating higher and higher ranked fighters after Felix became his manager.

As a boxer, Walcott used a lot of intricate footwork to gain the advantage over his opponents. This, combined with deceptive head-work and quick reflexes meant that for such a big man he was very difficult to hit.

But he hit like a truck, by all accounts. This was magnified by him often leading his opponents into traps and breaking his own rhythms to effectively 'walk' his foes directly into a knockdown punch. I know just enough about boxing to know how hard it is to avoid being punched in the face, let alone do it consistently and seemingly effortlessly.

Walcott eventually became the heavy-weight champion, only surrendering his title after a long and hard fought-match against Rocky Marciano in 1952. In his late thirties, Walcott became the oldest man up to that point to gain the title of champion until George Forman claimed the same at age 45 some years later.

Walcott would go on to become a sheriff of Camden and a leading community leader after his retirement, outliving Bocchicchio.

My great-aunt had her fair share of stories to share starring Walcott due to her proximity to Felix, but those stories will have to come at some other time when I can recover my notes and clarify a few things with my aunt.

Anyway, back to ducks.

I've wanted to get my ducks in a row for a long time and write down something about my great-aunt's memories and the associative properties of history. It took an interview that lasted a mere quarter of an hour to spur me to write about it after years of knowing the bare-bones of her past.

The ducks will never be perfectly in a row to write about something, that perfect opportunity is a horizon, not a physical or mental object. This is a meandering blog, but a meandering something is better than an organized nothing that doesn't peep beyond the barriers of my mind.

I'm writing, because if I don't write, my aunt's memories will vanish as surely as if they had never existed, and I feel compelled to write, something anything, to keep a record as best I can.

Further reading on Felix can be found here.

Further reading and interviews on Walcott can be found here.