In which we talk about what we can trust, historically.

What follows is a list of sources that have proved helpful to me while reading up on the Italian Renaissance. It is not complete--it is not even thorough, but I think it is a good start.

After all, an opinion without citations to support it is functionally worthless for our purposes.

Written Sources (in no particular order):

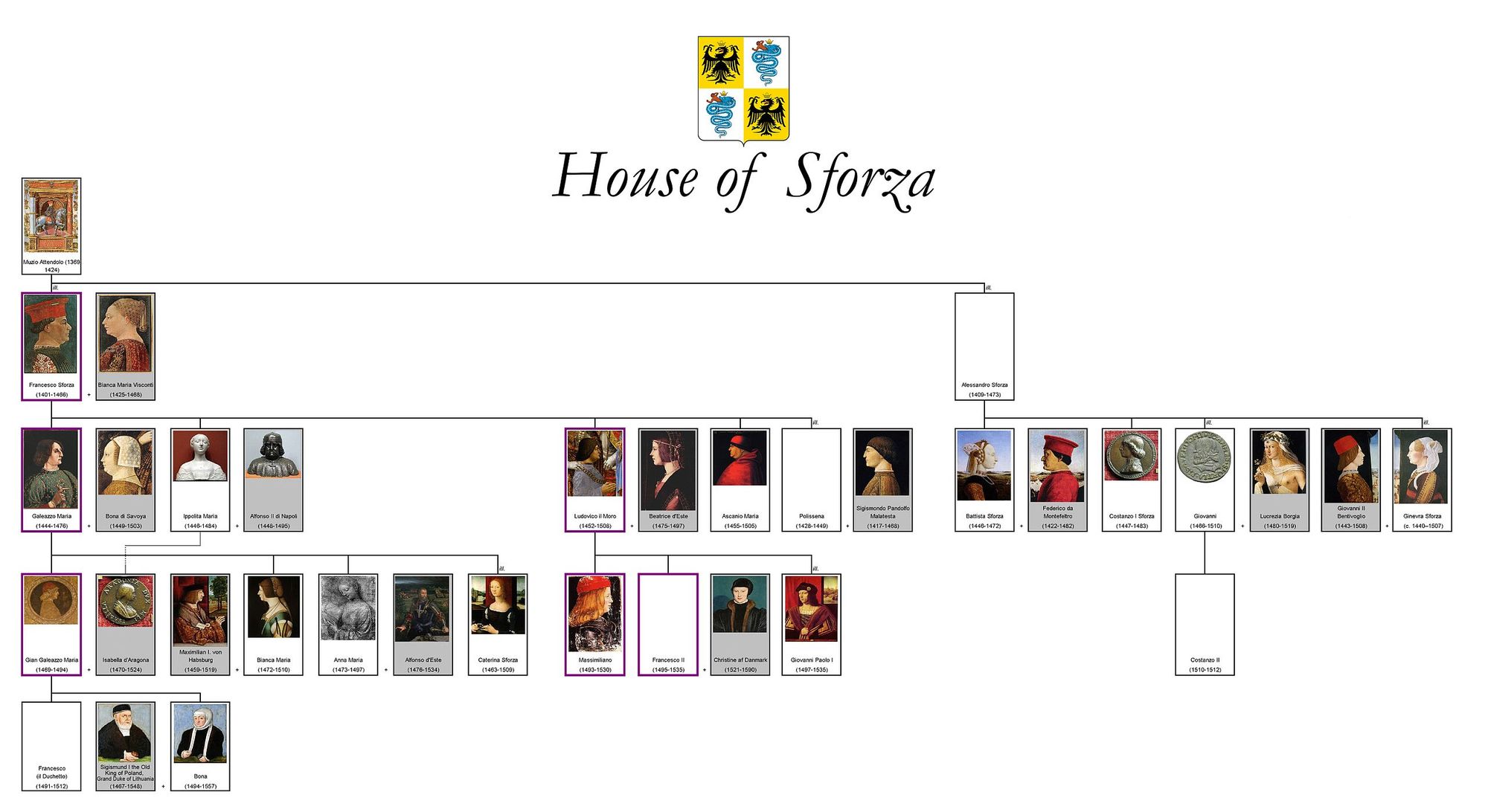

An in-depth look at the meteoric rise and later brutal fall of the Sforza dynasty that originated in Cotignola and through force and trickery, came to dominate Northern Italy (Milan), supplanting the Visconti family to do so. Covers all the major Sforza players that we'll soon come to see in The Borgias: Ascanio Sforza, Ludovico Sforza, his superlatively badass niece Caterina Sforza, the whole crew.

An older text, but still good for understanding the general trajectory of this family and how it interacted with the other major powers of its time. Not necessarily an easy read, as Collison-Morely's writing style can be a wee bit stilted, but worth the effort.

2. Barbarians, Marauders and Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare by Anthony Santuso (2004)

This whole text is not required reading, but it features a penultimate chapter that was my introduction to the condottieri of the Italian Renaissance that is very helpful in understanding the course of the Franco-Italian wars (the first of which we will see erupt in The Borgias) and why Italy was such easy pickings for Charles the Affable's army. It also features a nice biography of Erasmo da Narni, a mercenary captain whose nickname was Gattamelata ('Honeyed Cat') and while he died well before the show takes place, understanding his life of perpetual side-switching soldiery helped me get a feel for Italy before the French invaded in force in 1494. Erasmo was apparently a good-egg among mercenaries for hire, to hear Santuso tell it, repeatedly instructing his men to spare women and children when they would sack towns. While this claim shouldn't be taken at purely face value--an order given is not an order necessarily obeyed--Gattamelata did accumulate enough wealth and good will to have an equestrian statue of himself made by Donatello in Padua that survived. A good reference book.

3. Mercenaries and their Masters: Warfare in Renaissance Italy by Michael Mallett (2013)

This is the in-depth book necessary to understand the condottiere system of Renaissance Italy. Mallett covers the origins of the system adapted by the Italian-city states which were engaged in constant warfare, but seldom total war. The borders of provinces were often re-drawn, and the way for many young men to make their way in the world was to enlist in one of the free-ranging companies (including our good friend, Muzio Attendolo, the progenitor of the Sforza dynasty who honestly deserves his own show but won't get one). Notable is Mallett's detailed treatment of the Battle of Fornovo--the first major battle of Italian Wars. The battle of Fornovo exposed the key weaknesses of the condottiere system against the French standing army as it retreated from the peninsula and first, embryonic stirrings of modern warfare emerging from the Renaissance. To understand what was happening--and why--on the battlefields of Italy during the timeline of the show, this book is essential as the Italians, the Spanish and the French all fought for profit, glory and survival. Cannot recommend this title highly enough.

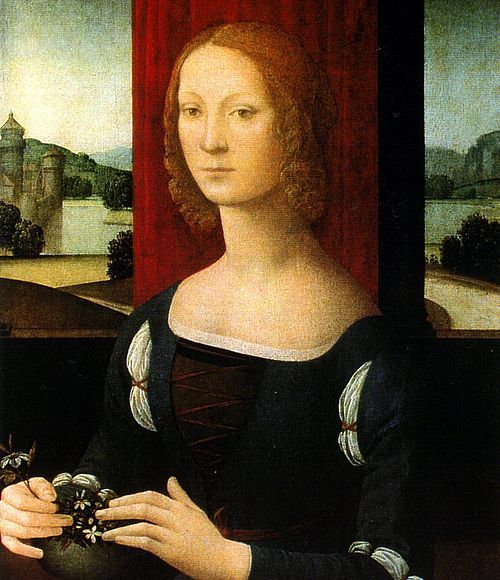

The definitive biography of Caterina Sforza. She was a remarkable woman who among other accomplishments, held Rome hostage for just over two weeks with artillery while nine months pregnant, outmaneuvered her husband's killers, and famously flipped off Cesare Borgia while under siege--and managed to outlive him. A woman of considerable guile, spirit and skill, to say the least. Lev carefully sources her arguments based on contemporary sources and does her best to correct exaggerated images of Caterina Sforza, like that time she was said to have sent a letter infected with black death to Pope Alexander VI (Lev views that as unlikely) in an attempt to assassinate the pontiff. I have plenty to say about the Sforza family--and Caterina in particular--and they'll be getting their own character pages as they appear in the show.

Of particular note in this book was Lev's documentation of Caterina's early interaction with the at the time wet-behind-the-ears Machiavelli, out on his first diplomatic mission from Florence, during which she showed herself to be shrewd as a negotiator and political actor. Machiavelli, no great respecter of women even for his time, would go on to pillory Caterina for displaying the same traits that he so admired in his later patron, Cesare Borgia--daring, cunning, and audacity.

5. The Prince and Other Writings by Niccolo Machiavelli, translation and notes by Wayne A. Rebhorn (The Prince and Discourses on Livy--1513. The Life of Castruccio Castracani--1520. Collection published:2003)

Oh Machiavelli. You're a vital guide that knew many of the actors in this drama personally. It would be disturbing if you weren't on my list of sources. His detailed portraits--particularly of Cesare Borgia, Rodrigo Borgia, and the man who ultimately undid all their hard work to establish a hereditary Borgia-Papal state, Giuliano della Rovere, reveal their virtues and flaws as seen by an astute political strategist and theorist. Essential reading for anyone hoping to understand the author, his subjects, the nature of political power during this time period.

6. Princes of the Renaissance by Orville Prescott (1969)

An excellent (and at times snarky) survey of the leading families of the Italian Renaissance. It's chapters on the House of Aragon--the rulers of Naples at the time of the shows beginning--was particularly helpful for getting a sense of the political landscape that shaped Italy. The chapter on Alfonso of Aragon was helpful to understand Spain's role in southern Italian politics, and it also explores the roles of his ruthless son Ferrante and screw-up grandson Alfonso II, both of whom will make an appearance in Jordan's show. Also covered, besides the Borgias, Sforzas and della Roveres are the noble houses of d'Este, Gonzaga and Montefeltro. Prescott's chapter on Ludovico Sforza ("A Prince of Very Rare Perfection"), who was a brilliant statesman of Milan that fatally overestimated his own machinations and foresight, was crucial in patching some holes I had in my understanding of the Sforza family dynamics.

7. The Decline and Fall of Practically Everyone by Will Cuppy (1953)

Used for the chapter on Lucrezia Borgia, in addition to general hilarity. Cuppy was a meticulous writer who made sure to source absolutely everything, no matter how ridiculous, he wrote on everything from animals to historical figures. He kept these factoids written on notecards, exhaustively rolodexed them, and then when he ran out of room in his rolodex would pin them to the walls to help him think.

Cuppy's chapter on Lucrezia takes the position that her incestuous relationship with her brother Cesare were likely calumny, and that she doesn't deserve the reputation for being a femme-fatale poisoner that has dogged her since her death. This is an increasingly common, and historically supported view of Lucrezia, since Rodrigo would leave her in charge of papal affairs when he was indisposed, which says volumes both about her competence as an administrator and her father's trust in her judgment. She was the Borgia who had anything close to resembling a happy life after the death of her father and brother. Cuppy is also fond of reminding us that Machiavelli died of taking too strong a purgative and shat himself to death, and that's worth remembering in dark times, isn't it?

8. The Outline of History by H.G. Wells (1920)

The standard by which other reference books should be judged by, in my opinion. HG Wells is never shy about venturing an opinion (and has whole sections where he defends his right to do so, which is both somehow delightful and provocative). His section on Machiavelli, the Catholic Church prior to the Reformation and on Italy as a whole is an excellent overview. Of Machiavelli's works, Wells writes:

"The enduring values of these books [The Prince, Florentine History, The Art of War] lies in the clear idea they give us of the quality and limitations of the ruling minds of this age. Their atmosphere was his atmosphere. If he brought an exceptionally keen intelligence to their business, that merely throws it into a brighter light."

Mr. Wells also goes onto say some rather unflattering things about Machiavelli's character, things that I fear are largely accurate and will be kept aside until Machiavelli shows up in the show proper.

9. The Borgias: Power and Fortune by Paul Strathern (2019).

One of the more recent works on the Borgia family. Strathern previously wrote extensively on the equally prolific (and far less historically smeared) de'Medici family. His detailed analysis of the Borgias goes rather in depth, as one could expect from someone of his experience. A handy guide to the machinations of Rodrigo Borgia in particular and his ambitious plan for Italy. Strathern and Lev clash on some particular regarding Caterina Sforza (Strathern tends to take incidents that Lev classifies as likely apocryphal at face value). This book demystifies the difficult process of the Borgias working with many of their enemies to make the papal state a family power--and a permanent one in the Romagna.

10. The Borgias and Their Enemies 1431-1519 by Christopher Hibbert (2009).

Hibbert's book is in many ways a forerunner to Strathern--not a surprise, the Borgias have always been easy to spill ink or film on. Hibbert covers the career of Pope Calixtus III (Alfonso Borgia) who got Rodrigo started in the church and climbing the long ladder to the papacy. Like Strathern, Hibbert has a habit of repeating stories about non-Borgia families that other scholars have deemed apocryphal as fact. However, what is notable is that Hibbert and Strathern both largely discount the 'Borgia incest' rumors (chiefly between Lucrezia and Cesare) as just that--rumors. This is important, because the rumors of incest in the Borgia family are a key plot device in Jordan's show--where they are treated as fact. Oy vey. Hibbert would have been available as a source for research during the shooting and production of Jordan's 2011 show (as would most of the things on this source list).

11. Julius II: The Warrior Pope by Christine Shaw (1993).

This is my favorite book of the lot, I must admit. Christine Shaw used a lot of for the time cutting edge tech--search engines, basically--to comb through archival materials to get primary sources for this book. As such there are letters from spies, court members, the extended della Rovere family, anyone who was even tangentially involved in the life of Giuliano della Rovere--from his time as a cardinal to his dying breath as pope Julius II. I draw heavily from Shaw's work, and with good reason: she paints a picture that is wonderfully complex politically, but makes della Rovere human. He is a contradictory figure--explosively angry one moment, conciliatory the next, openhanded and stingy, garrolous and spiteful, and above all strong-willed and stubborn. Under her hand, he feels like a member of my family, a person you don't have to like exactly--he's a noble, after all in an era where politics and casual violence were hand in glove--but by the time you finish the book you can admire this changeable, irascible man. Here is one of my favorite of Shaw's descriptions of Julius, towards the end of her work:

"He was the type of the plain-spoken, short-tempered, vigorous, impetuous, big-hearted man of action, of uncomplicated, genuine faith. A Franciscan he might have been, but he was never made for the religious life: he said of himself that he would have made a bad monk because he could not stay still. He should have been a soldier: with some training he might even have been a successful one."

Contrast that to Machiavelli's portrait of Rodrigo Borgia in The Prince:

"[Pope] Alexander VI never did anything, never thought of anything, other than deceiving men, and he always found materiel so that he could do it. And there was never a man who was more effective in swearing oaths in affirming a thing with greater promises who kept his word less. Nevertheless, his deceptions always succeeded for him according to his wishes, since he really knew this aspect of the world."

You have great narrative tension between these two extremes of personality. della Rovere was impulsive yes, but he wasn't stupid, while Rodrigo made prevarication and formality into art forms and weapons to ensnare his foes. You, as readers (and as viewers of the show) can feel the contrasts--della Rovere might swear and fume and curse (or maybe even throw things at you), only to relent once the rage passed. Whereas Borgia might smile and tell you what you wanted to hear, only to betray you when the moment was right.

The two of them, Borgia and della Rovere went back and forth from late 1492 onwards--using each other for their own advantage from several removes and locking horns until Rodrigo's death in 1503, through two wars and countless maneuverings and thwarted traps. This is a solid dynamic that screams for great television. We'll see what Neil Jordan does with this relationship, which was practically handed to him on silver platter.

Online source:

Ada Palmer's wonderful multi-part series on Machiavelli and Utilitarian ethics also covers the rise and fall of the Borgias--and introduced me, years ago, to the cantankerous figure of Julius II. I cannot recommend it highly enough--Palmer is wonderfully witty, thorough and entertaining throughout.

Part 1

And even better, she has a wonderful piece at Tor talking about the differences between Neil Jordan's production of The Borgias and the European production covering the same subject--and how while both fictive, the differences in how the shows convey plot, setting and message in history.

That's all I have for now. Soon, so soon, we will return to Neil Jordan's The Borgias. Foreheads will hit desks. Entire timelines will be rewritten with no acknowledgement of same and some good acting will happen.