More Missed Opportunities

(Warning: A great deal of historical quotations from the wonderful historian Christine Shaw, sarcasm, historical deep cuts, narrative questions and pictures of coins ahead. You were warned.)

The 1492 Papal Conclave was a complex event, so of course Neil Jordan skipped over the interesting parts to get on to some sub-par murders.

To understand Italian Renaissance Politics, I like to recall a line from the Greek playwright Sophocles. The words come from ever-wily Odysseus: “Friends one day, all hostile the next.” Another translation is: “A friend today, a foe tomorrow.”

This quote is also applicable in reverse--today's enemy may be tomorrow's ally.

This is key to understanding the Italian Renaissance, particularly the political and military machinations of all major actors. You can't even trust members of your own family to necessarily act in your interest.

Point the First: Guiliano della Rovere and Unlikely Alliances

First things first. Giuliano della Rovere absolutely hated the Borgias. This does not make the Borgias unique--Giuliano della Rovere hated a lot of people. It was one of his hobbies.

We mustn't mistake the act of hating someone's guts as also meaning 'discarding all potential utility from them'.

But the much popularized life-and-death rivalry between Borgia and della Rovere was by no means fated. The nature of politics--that your ally today may be your foe tomorrow, and your nemesis your life-saver the day after that--meant that della Rovere often had to pal around with people he personally despised. Like this guy.

Giuliano della Rovere had demonstrated that he could work with old enemies if it served his interests. Take, for example, that time he struck up an odd alliance with Virginio Orsini, the same Virginio Orsini who had promised publicly desecrate his corpse during the reign of Pope Sixtus the Fourth.

The Orsinis had been in rebellion against the papacy at the time, siding with Naples and sieging Rome, as mentioned above. Giuliano della Rovere had been the Pope's go-to guy, so naturally they were at loggerheads. Both men vowed to show one another what was what if they got a chance. But the war ended before they could duke it out with each other, leaving an awkward tension in the air.

Christine Shaw, Giuliano della Rovere's biographer summarizes their relationship nicely:

"One of Lorenzo d'Medici's less celebrated, but in its own way, dramatic, diplomatic successes had been the formal reconciliation of Virginio and Vincula [Vincula was one of Giuliano della Rovere's holdings and is used as shorthand for him throughout the text--compare Machiavelli's constant references to Cesare Borgia as 'the Duke of Valentino in his own text] in 1488. Virginio had said then that if Vincula did not fulfill his promises, he would treat him as a 'deadly enemy', but by the summer of 1492 he was quite willing to cooperate with the cardinal. Rome now witnessed the curious spectacle of Virginio Orsini canvassing support for Vincula's candidates in the conclave only six years after he had threatened to parade his head through the streets on the point of a lance."

Giuliano della Rovere had no problem working with old enemies, is the take-away here.

Point the Second: A Non-Destined Rivalry

The show takes great pains to show Giuliano della Rovere (San Pietro ad Vincula, Cardinal of the Church and inveterate loudmouth) and Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia as on an unalterable collision course. Their rivalry is portrayed as inevitable--largely, because Giuliano della Rovere is miffed that Borgia succeeds in ascending to the big chair instead of him. Let me open up my Christine Shaw to address that motivation:

"The Milanese suspected Vincula [della Rovere] of harboring ambitions to put himself forward as candidate, but their suspicions were probably unfounded. He was one of the longest-serving cardinals, but he was still, given his hale and vigorous constitution, rather too young--probably not yet fifty–to be a serious candidate. The cardinals rarely elected anyone who looked as if he would last for much over a decade. Ascanio, too, was far too young to be a candidate himself, but he and Vincula were unquestionably the power-brokers of the 1492 Conclave."

Anyway, more on the conclave itself in a little bit. Back to Rodrigo/Giuliano's dynamic after the conclave.

Sure, della Rovere didn't have any warm and fuzzy feelings for Borgia, but in keeping with the 'enemies one day, friends the next' theme introduced above, there is no evidence he viewed Borgia as an existential threat at first.

della Rovere had been in papal politics for over twenty years at this point. He knows who Rodrigo Borgia is. Just wanting him not to be pope is not enough to make them enemies eternal. Plenty of people didn't want Rodrigo to be pope until they saw the way the wind was blowing. Christine Shaw, one of della Rovere's pre-eminent biographers, puts it this way:

"That Vincula [della Rovere] did not want Borgia to be pope did not mean that they were enemies before the Conclave. He had been his colleague in the College of Cardinals long enough--over twenty years--to have realized how clever, how ambitious and how unscrupulous Borgia could be. Perhaps Vincula, hoping to maintain or even increase his own influence, simply preferred a man who could be more easily dominated, but his behavior from the first months of Alexander's pontificate suggests that there was more to it than that. He plainly believed Alexander to be fundamentally untrustworthy, to be capable of treachery and violence--and this before any of the notorious scandals that were to make the Borgia papacy so infamous. Renaissance Rome was no community of saints and Vincula need not have felt shocked or affronted by a man such as Borgia being a cardinal to feel he was not a man to be entrusted with the powers of the pope."

Nor was this a fight-on-sight, when Rodrigo Borgia became pope Alexander. Indeed, his first promotion wasn't even a contested claim. I turn again to Shaw's work:

"Conflict between Giuliano della Rovere and the new pontiff was not inevitable, and certainly need not have arisen as rapidly as it did. It was said that Alexander made him offers which he refused to 'preserve his good name and integrity' but that he remained a very powerful figure. He had no objection to the first cardinal Pope Alexander promoted, on 31 August, Juan Borgia Lanzol, Bishop of Monreale; indeed it was later reported that they had been close friends..."

Yes, the first person to get a cardinal's hat was a Borgia, but he was also a close chum of Giuliano della Rovere. This 'immediate and permanent hostility' between Borgia and della Rovere is a product of hindsight and knowing how everything turns out in the end. One of the foremost blindspots in understanding (and enjoying) history, is to back-date motivations and inclinations to historical figures to fit a narrative that was already dangerously simple, and that is exactly what Jordan has done with The Borgias.

(And to give credit where credit is due, della Rovere absolutely did pitch a shit-fit when Borgia rapidly nominated and confirmed thirteen cardinals to the college. In the show, he bears this with icy stoicism--in the historical sources quoted by Shaw, Giuliano della Rovere went off to a private room yelling like mad and hitting the walls).

Ok, I should back up a bit and talk about the politics behind the conclave of 1492. And the actual conclave, that was just kind of brushed over in the inaugural episode of The Borgias.

Part the Third: the Politics of the Papal Conclave of 1492

So, who are the major players going into the 1492 Conclave that ultimately picked Rodrigo Borgia to wear the pope's miter? The way the show frames it, the contest is between della Rovere and Borgia

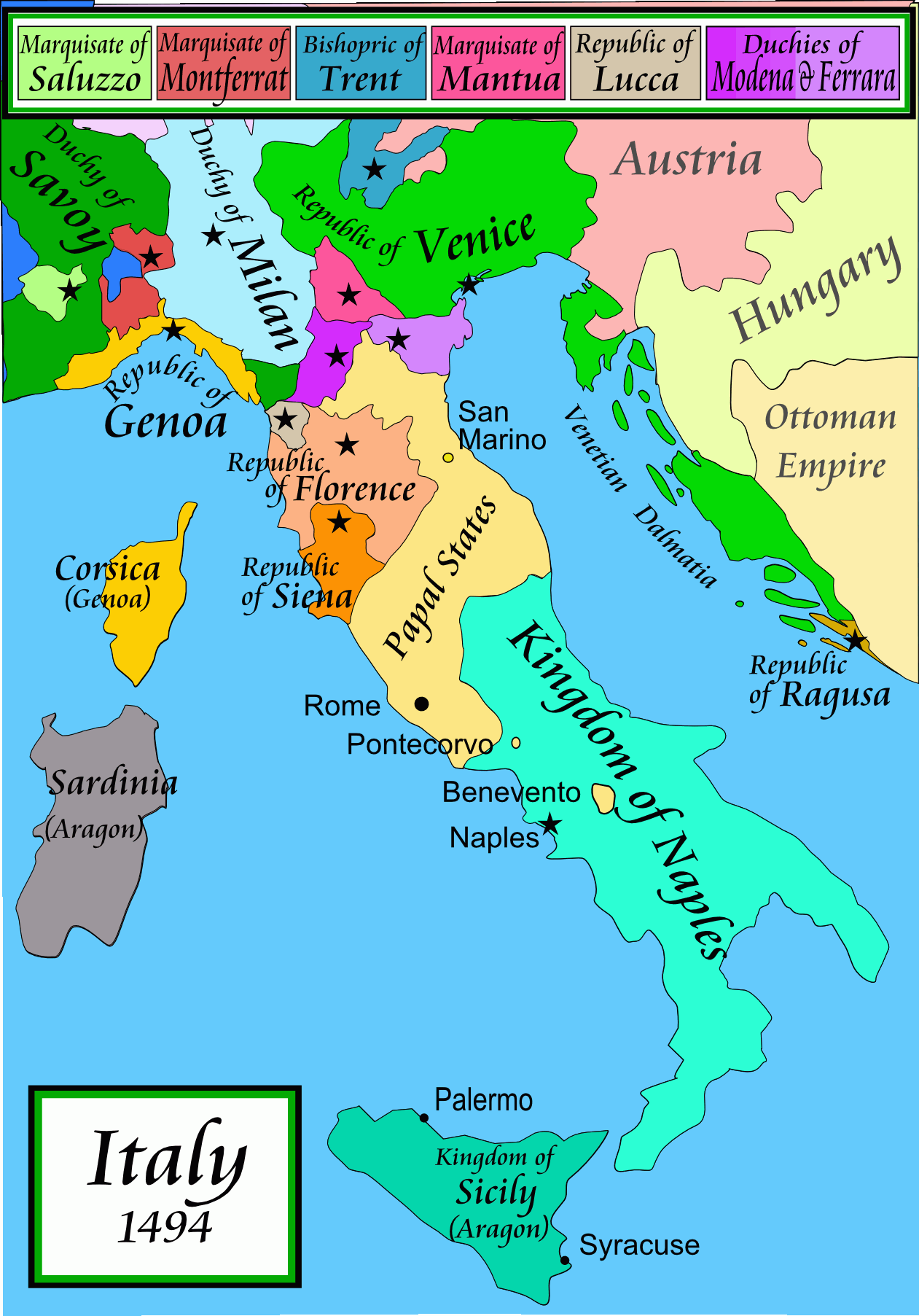

Let us turn to our good friend, geography! (This map is two years upstream, timeline-wise, but the major borders are the same.)

Milan (North Italy, Milan, ruled by Sforza family) Hates Naples. Yes, they hate them so much that they can ignore the normal rules of grammar and get a capital letter.

Naples (Southern Italy, ruled by the House of Aragon under King Ferrante) Hates Milan. See above note on the power of hatred, even diluted over centuries, to influence grammar on a blog. The House of Aragon had conquered Naples three generations ago, and it only got worse from there.

There is a lot, a lot of bad blood between these two factions. Hatfields and McCoys level, Crips and Blood type rivalry.

And one of the key mechanisms of advantage between these two sides—besides military might—is the papacy. Both north and south Italy want a pope that is firmly aligned with their interests and can help make the other side suffer.

Having a pope that is Pro-Naples is in King Ferrante of Naples interest. At least, if he can’t have one that will support his agenda in Naples, a notoriously fractious and restive place to rule, he can get one that is anti-Milan. King Ferrante and his vicious screw-up son Alphonso II are a topic for a later discussion, but they were no peaches, temperament-wise.

So Giuliano della Rovere is King Ferante’s guy on the papal conclave. Christine Shaw, della Rovere’s biographer, notes that it was less out of being pro-Naples and more being anti-Milan that brought Giuliano della Rovere onto Ferrante’s side. As you will see, Giuliano della Rovere had a long and troubled history with the Sforzas, stretching back decades. That and the truly ridiculous amount of money that king Ferrante gave him to spread around to see the cardinals voted their consciences.

On the other side of this is the one Sforza representative in the higher clergy, Ascanio Sforza. He was a masterful political intriguer, easily the peer of his brilliant brother, Ludovico Sforza who ruled Milan in all but name and later would help author so much trouble for Italy in two short years. Which is to say that he was a snake among snakes and always knew which way the wind was blowing. He was the lone Sforza in the papal power-structure proper, but more than made up for that with cunning.

So, unlike in the show, the main tension in the conclave was between Ascanio Sforza and Giuliano della Rovere. Both of them spread copious amounts of money around to convince cardinals to vote their way. Several rounds of voting come and go--no conclusive result, no front-runner even.

Finally, here comes Rodrigo Borgia as a way to break the impasse. Rodrigo’s actions just before the conclave put him in a good, but not inevitable position. He married his daughter Lucrezia into the Sforza family in 1491 (Giovanni Sforza, no catch even by Sforza standards but I digress) and was working on sweet-talking the Orsinis, through titles and copious money. By doing this he's secured a tenuous alliance with both the local Roman power and the north of Italy. He's positioned himself very well indeed to make a move, and as we know, he does--but his success was by no means guaranteed.

Ascanio demands the position that Rodrigo holds--vice-chancellorship, basically the secretary of finances, a VERY lucrative position with a lot of plum estates, in exchange for supporting Borgia. It's a no brainer for Rodrigo, who takes Ascanio's offer in nothing flat.

The Borgias came out on top with the help of the Sforzas and Orsinis and consolidated their rule with the help of these two powerful families. The same Orsinis that Jordan paints as hostile to the Borgias as a body? The Orsinis were key in the Papal states expansion into the Romagna under Cesare Borgia and expanding the power of the Papal state before they ended up on the wrong side of the cleaver? You know, those Orsinis who the writers of The Borgias annihilated in the clumsiest B-plot in the first episode this side of The Walking Dead? Yeah, those Orsinis.

Part the Fourth: the Sforza Awakens

Ok. So if Giuliano della Rovere failed to get a candidate friendly to Naples elected to the papacy, that's not great. Despite his liberal spending and promises, he ultimately couldn't deliver. King Ferrante was unusually understanding about this--sometimes, those are the breaks. He'll try again with the next pope, he doubtless thinks.

There is some reason to believe that the thing that helped escalate the della Rovere/Borgia feud was not their antagonism and long knowledge of each other, but the machinations of the Sforza family, specifically Ascanio Sforza. To quote Christine Shaw:

"It was not the influence of Cardinal Monreale, but that of Cardinal [Ascanio] Sforza that disturbed Vincula [della Rovere]. Ascanio' maneuvering in the conclave had reaped its reward, and his dominance at the papal court was clear and acknowledged by Alexander himself. It seems to have been Ascanio on whom Vincula focused his attention and mistrust much of the time, and he was, if anything, more wary of him than the pope. Conversely, it is not clear how much of Alexander's suspicion of Vincula was prompted by Ascanio. The pope was rather timorous by nature, for all his intelligence, experience and apparent self-confidence. Seeds of suspicion, whether or not they were sown by Ascanio, began to germinate in his mind within weeks of the conclave."

So The Borgias rendition of the papal conclave gets the results broadly right: in the show as in the historical record, Ascanio Sforza supports Rodrigo Borgia to the papacy by buying the chancellorship from the Spanish candidate. However, they get a lot wrong getting to that result.

-The show neglects the critical role of the Orsinis in the Borgia power base, opting to cast them as villains who are swiftly disposed of.

-Ascanio Sforza's role is massively downplayed in the show, making him essentially a Borgia lackey rather than the magnificent bastard and political power he was in the historical record.

-The show fundamentally misunderstands the underlying tensions of papal politics at the time, and while they expand on king Ferrante's role in the conclave in later episodes, knowing about the desires and funding from other parts of Italy.

-The show also misrepresents the role and the importance of Giuliano della Rovere. The current historical thinking is that he was acting as an agent and advocate for Ferrante's interests and had no real chance of seizing the big chair himself--he was far too young to be pope.

-The show sets della Rovere up as an implacable enemy to Rodrigo Borgia--well before he had any real reason to hate him more than any other person. The fallout between San Pietro ad Vincula and Pope Alexander VI was a protracted process rather than a sudden one.

-The key to early Borgia dominance and expansion into the Romagna was the 'triple alliance' between the Orsini, Borgia and Sforza families through marriage, money, and common interests. The show elects to murder the Orsini in the first two episodes for reasons that apparently three families is too much to remember.

Onto episode two. I think I may have to make mini-biographies, timelines and maps just to keep up with the farrago of historical errors that is this show so far. But I will do my best to point out when Jordan, the camera-men and actors do something right. Till next time, comrades!

Want to know when I post and get a head start? Consider subscribing! Or don't! Either way, you made it to the end, and isn't that worth celebrating?