I'll be using this page to discuss my chief sources for the episode, and series in general. Louis XV shambles through managing France, innocent people are attacked by a mysterious Beast and Louis welcomes the distraction from his abysmal record.

Sources that will be used throughout the series that Feature in this Episode: (Print Texts)

Smith, Monsters of the Gevaudan: Making of a Beast

The absolute backbone of my research. Smith covers everything from the 7 Years War (and how that effected the French psyche), the horrible economic woes that come with losing it, and the relationship between the press and monarchy. Smith draws a great deal from primary source documents (Duhamel and Syndic Lafont's letters in particular are highly engaging) and understands that there is no singular history of the Beast: the international press of the day had one version, the aristocracy had another, and the people of Gevaudan had another still--each with its own mythology. I cannot say enough good things about this work--I'll be quoting it frequently.

Taake, The Gévaudan Tragedy: The Disastrous Campaign of a Deported ‘Beast’

This is the most recent scholarship on the Beast. It focuses on the fact that the Beast's mannerisms fit more closely with an ambush predator--more cat-like than dog-like--and this includes victim choice, taking prey that would usually have been outside of a wolf's weight class. Combined with a bevy of chart and local autopsy reports, this work makes a persuasive case for the Beast of Gevaudan being a lion escaped in transit to one of the menageries of the nobility.

Quammen, David: Monster of God. The most in-depth look at man-eating predators I've ever read. Quammen moves smoothly from mythology to biology, from biology to history, loops around anthropology and ends on a speculative note--a world naked of humankind's oldest neighbors: big carnivores.

Quammen does not explicitly deal with wolf-attacks on humans--always a touchy subject in America--he focuses on big solitary predators: bears, crocodiles, tigers, lions. However, Quammen's precise and lyrical writing style does grapple with the broader trends of maneating in a historical and economic sense, which was invaluable for viewing (and reviewing) accounts of the Beast of Gevaudan.

Quammen is an old hand at writing about contentious creatures--the first bits of his writing I ever read as an impressionable teen were about the conflict/symbiosis between the Massai people and the local lion populations in Kenya. I'll be referring to this book throughout, and will leave you with a quote:

“It’s a general truth if not quite a universal one, relevant from Rudraprayag to Komodo to Tsavo, sometimes noted but seldom quantified or analyzed: predation is costly and the costs are unevenly distributed. Large predators cause more material loss, inconvenience, terror, suffering and death among poor people (specifically poor people who live in rural circumstances within or adjacent to the habitat) and among native peoples adhering to traditional lifestyles on the landscape (who may only be ‘poor’ in the sense that they aren’t insulated by material wealth and have little political power) than to anyone else. Proximity plus vulnerability equals jeopardy.”

Web-resources:

For digital sources on the Beast of Gevaudan, this one was particularly helpful. It has some very handy tables on the Beast attacks (very helpful for sussing out some of the five w's--who what when where and that damnable why). The site is partly in French (though it can be set to English) and they feature interviews, articles and additional resources largely around this mysterious creature. Also features a handy synopsis of the various theories about the Beast's identity.

I was able to purchase a history of the images of the Beast from this site--the Beast, since the press took notice in late 1764--has always been a celebrity of some-sort to someone and the papers of the time (and media of today) reflect that fact.

The Beast has gone from a terror to a mascot of Lozere (formerly Gevaudan): tourist trinkets, statues, themed inns, the works. Lebetedugevuadan.com is a very handy reference guide to all things pertaining to the Beast itself.

Trey the Explainer: the beast of Gevaudan

An excellent summary. The author leans hard on the hyena theory, but also assesses the role that mass-hysteria can have in inflating an already tense situation that exacerbates existing economic and social tensions--making people see the Beast where perhaps there was only a common wolf or nothing at all.

A Smithsonian article chronicling the Beast's mythological inflation through time.

An article in Forbes about how the geography of Gevaudan influenced and frustrated hunts for the beast--specifically, the presence of underground rivers and thin topsoil.

History of the 7 Years War:

A wonderful blog on Canadian history provided me with the global map on the 7 Years War.

A somewhat deeper dive into the build up to the 7 Years War and the previous ruler of France can be found here.

Fox and Wolf Stuff:

Another Type: The Tail-Fisher A blog that examines the many variants of Renard the Fox tricking the slow-witted wolf into going ice-fishing with his tail as the lure--in the dead of winter.

Terry, Renard the Fox

Mann, Ysengrimus

Both of those primary sources left a deep impression on me. I began studying them years ago--and they never really left my brain. They don't feature in the narrative of the Beast of Gevaudan (except to inform us about French attitudes towards foxes, clerics and the nobility in a bygone era) but the stories are too memorable (and crass, and funny, and dark, and cynical, and and and) to except completely from any story that even touches on either animal. The feud between Renard and Ysengrimus clearly resonated through Europe--almost every country has an adaptation of their battles, adapted for time and space. One of my favorites is a Russian adaptation (1992) where Renard goes to visit Ysengrim (Sergunya in this version) and complains that ever since he met an American from Colorado, he's become an altruist--and his life has become nothing but suffering. Of course, this is as big a lie as it is possible to tell--but the fox complaining to the wolf serves as a framing device through which the stories of The Roman de Renard and Ysengrimus are retold). I've put the link below.

More Wolf Stuff:

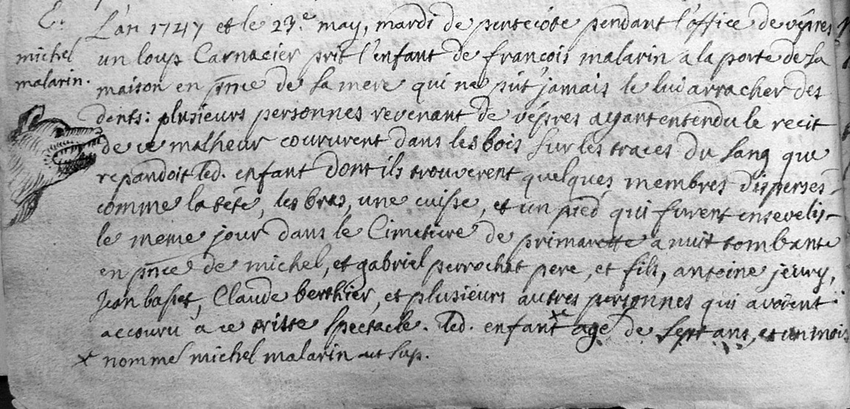

The Story of a Man-eating Beast in Dauphiné, France (1746–1756)

This was one of the more formative articles in shaping the direction I took with the opening video. The paper covers a period immediately before the Beast attacks in Gevaudan, but hits many of the same notes. While other authors listed here (Taake, Quammen, Smith) all mention that France had a chronic problem with wolves, this was the paper that truly brought home to me how deeply rooted the problem was.

And there were other high-profile animal attacks on people, particularly by wolves, throughout French history. The wolves of Paris laid the city to siege in 1450 during a particularly harsh winter. Their attacks were only ended when an enraged mob shepherded the wolves before Notre Dame cathedral and stoned them to death.

And even at the same time as Beast-mania seized France, wolf-attacks didn't let up. The most notable was the wolf of Soissons who attacked 18 people (killing four) in two days not far from Paris before being put down--likely rabid.

And of course, Perrault finished his adaptation of the older (and dirtier) Red Riding Hood tales in 1697, so we can't in conscience finish this blog without mentioning that.

Just for Fun:

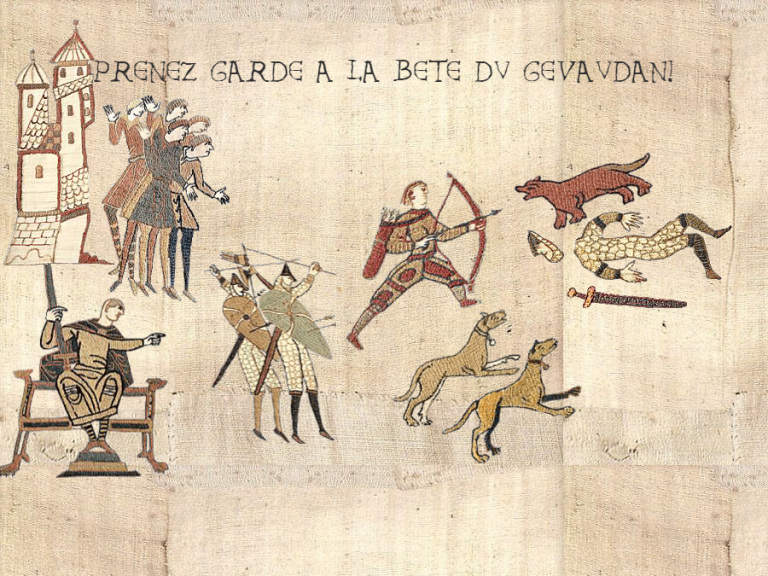

The Beast of Gevaudan (if it was portrayed in the Bayeux tapestry) comes from this excellent blog, and sadly, I couldn't fit it into the show proper:

My favorite two quotes that couldn't make it into the show:

"He [Louis XV] was the most excellent of men but, in defiance of himself, he spoke about the affairs of state as if someone else was governing.” --Duffort de Cheverny, royal courtier.

“Landscapes have the power to teach, if you query them carefully. And remote landscapes teach the rarest, quietest lessons.” --David Quammen.