October is a traditionally busy month, not just for me but I suspect for everyone.

So, two bits of interesting news.

1) The Philadelphia Dramatists Center picked up one of my scripts for their Halloween Zoom Reading! It's a short play adapted from a short story of mine based on the line between alternate history and horror. In short--what if Bram Stoker's dreams co-mingled on the night he said he was inspired to write Dracula?

(Hint: it involves, of all things, seafood).

Stories wander before they settle. I originally was researching a paper on the differences between how the Slavic world saw Vlad III as opposed to the European conception of Vlad III, the historical figure who is better known as Dracula. So I went to the Rosenbach Museum to do some digging.

Stoker was obviously a key part of my research--having given Vlad III an adrenaline shot of post-mortem immortality with the publication of Dracula in 1897. Florescu and McNally provide very interesting analysis of how Dracula is viewed by 3 different geographic regions after his death. Dracula's legacy can be roughly summarized as followed, prior to the publication of Stoker's work (And to an extent, afterwards--as a historical figure separate from the idea of undeath).

1) Western European view of Dracula: Largely negative, due to the very well-documented atrocities against the Germanic Saxon minorities, such as the massacre at Timpa Hill--you may remember this incident from references to Vlad III taking lunch among the impaled Saxons while their church burned in the background.

For this, and a plentitude of other crimes--recorded, ironically, by the same Saxons he persecuted and spread through Europe--Vlad III's exploits became the source of horror-stories spread through Western Europe. The historians Florescu and McNally record that abbots in abbeys had to chide monks for in effect telling scary stories about Vlad III's latest gruesome exploits.

Monks seemed to be always on the lookout for distracting and juicy stories to spice up their days--centuries earlier, Danish monks were scolded for scratching graffito of ravenous and comically stupid Ysengrimus the Wolf in their cells instead of saying their devotion to the Blessed Virgin.

The monks and clerics of the time during and just after Vlad's reign were copying the accounts from the Saxons fleeing Wallachia and it mushroomed out from there into a small cottage industry. Over the top violence is a seller no matter where or when you are.

In short, Vlad's murderous and repressive reputation led to him being a proto-meme throughout Western Europe after his death, though by Stoker's time he was a relatively obscure regional figure. This "horror movie" tone can be found in the first lines of the 1488 Nurnberg pamphlet [Vlad III died in 1477]:

"In the year of our lord 1456 Dracula did many dreadful and curious things.

ITEM: The old governor had the old Dracula put to death, and Dracula and his brother gave up their faith and promised and vowed to defend the Christian Orthodox faith [Sidenote--a condition for Vlad III's 3rd reign over Wallachia was his conversion to Catholicism--the religion of the Saxons, who he ruthlessly persecuted. He took the deal].

ITEM: In the same year he was appointed lord in Wallachia. Immediately he had prince Lasla [rival claimant for the throne of Wallachia] killed who was lord of this country. Soon after this he had villages in Transylvania, also a town by the name of Beckendorf in Wurtzland burned. Both women and men, young and old perished. Some he brought home with him to Wallachia and impaled them all there."

The Nurnberg pamphlet continues in much the same matter throughout. Vlad's reputation with Western Europe was pretty much sealed and would remain so until Stoker catapulted him back into the wider consciousness.

2)Slavic world view of Dracula: A proto-Machiavellian figure who has some handy tips for administrating a state through terror.

Russian diplomat Fyodor Kuritsyn’s account of Dracula’s life (Skazanie o Dracule Voevode, The Tale of Voievod Dracula, 1486) is short. At less than four thousand words in its English translation, this diminutive document barely cracks ten pages on a word-processor. That’s not much for a tiny document that changed the shape of Russian history, political thought and administration.

He certainly hadn’t set out to do this—Ivan III had sent Kuritsyn out from Muscovy to see what he could see of Europe, conduct and seal an alliance against the Poles and recruit Europeans of talent and skill to help bring Muscovy up in the world. “Opening up the windows [to Europe],” is how Florescu and McNally put it.

Kuritsyn did all this, and also came across the legacy of Vlad III, becoming “fascinated to the point of absorption” with the Wallachian.

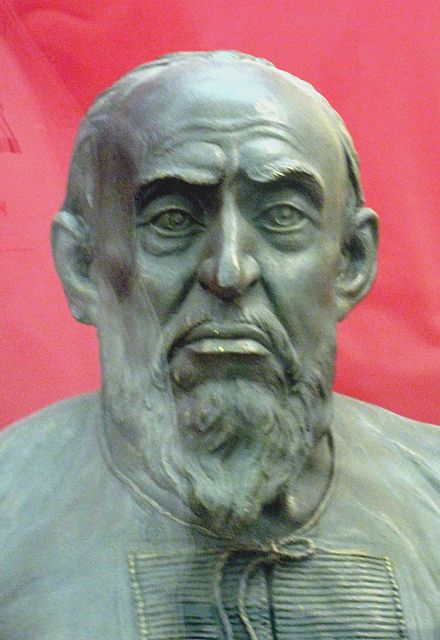

Kuritsyn became the most notable individual til Bram Stoker’s (re)discovery of Dracula centuries later to become enthralled by the memory of Vlad. Kuritsyn pursued and interviews all those who had known Vlad III in life: his captor and king of Hungary Matthias Corvinus, Vlad’s childhood friend Stephan the Great of Moldavia, Vlad’s widows, and his surviving children. Alongside this cast he talked to Vlad’s remaining partisans and men who had been at the battle of Snagov where Vlad was killed. Kuritsyn even spent time at Brasov, the sight of Vlad’s infamous Timpa Hill massacre, interviewing the Saxon survivors eight years after Vlad’s death.

Kuritsyn brought back his observations and records in the chronologically scattered, but still fascinating Skazanie o Dracule Voevode.

Inside this document (which I will quote at length) Kuritsyn does his best to extract what practical advice for rulers from Vlad’s life. This is a document was circulated among the royal family. Ivan III, Ivan the Terrible's grandfather, clearly took some tips on dealing with foreign powers from Vlad III, if the histories that report him nailing turbans from the Mongol emissaries to their heads (A clear bit of inspiration from Vlad’s similar treatment of Ottoman dignitaries recorded in the Skazanie o Dracule Voevode's opening pages). Here is the opening passage:

There was [once] in the country of Muntenia a Christian Voievod of the Greek faith, whose name in the Vlach language was Dracula, which means “devil” in ours. He was so evil that his life was the image of his name.

One day ambassadors from the [Great] Turk came to him and when they were brought before him, they bowed according to their custom but did not uncover their heads. Therefore he asked them: “Why are you behaving this way? You are before a great sovereign and you outrage me in this way?” To which they replied “Such is the custom of our sovereign and our country.” And Dracula said to them: “Very well, I shall strengthen you in your custom. Brace yourselves!” And he ordered that their turbans be nailed to their heads with small iron nails. Then he dismissed them saying: “Go and tell your sovereign that if, on his part, he’s accustomed to accept such shamefulness, we for our part, are not accustomed to that. [Tell him] that he will not impose his customs on other sovereigns who do not want them, but let him keep them for himself.”

Florescu and McNally are swift to point out that Ivan the Terrible would go on to recreate and elaborate upon some of Vlad's more spectacular instances of state-terror. Most notably, the predilection for impalement and the recreation of the famous 'hat-nailing scene'. To be specific:

"Dracula’s standards for diplomatic protocol found their way into the Chronicle of Kazan, drafted on the tsar’s orders. Ivan made frequent use of impalement in killing boyars and other political enemies—a method of imposing death rarely used in Russia before his time and obviously inspired by Dracula…"

Skazanie o Drakule Voevode would become later published in the 18th century along with other classics of Russian antiquity—sitting alongside such classics as The Saga of Ivan Tsarevich. It was this combination of Vlad’s theatrical cruelty, administration through terror, and insistence on the divine right of rulers, mixed with Ivan Grozny’s temperamental nature, horrific childhood, and exposure to the deeds of others like him, that would give birth to Russia’s first secret police, the oprichnina.

The redoubtable historian Matei Cazacu opines, in closing:

“The message Kuritsyn transmitted via the Skazanie o Drakule Voevode resonated down to the times of Ivan the Terrible, a tsar autocrat par excellance, exalted by some as the principal founder of the Russian empire (with Stalin in last place), and scorned by others as a bloody tyrant in the image of Dracula. The tsar had surely read the Skazanie o Drakule Voevode…”

Summary: Vlad III's reign may have done more to shape Russian history and political practices than anyone could have had any reason to expect or imagine.

3) Romanian view of Dracula: Harsh but just, gets the Robin-Hood treatment for sticking it (sometimes literally) to the Ottomans. In this iteration, Vlad III of Wallachia is a hometown hero who instituted cruel-but-fair policies and who showed the oppressive boyars who was boss. He is lauded for defeating the Ottoman invasion of Wallachia [for the given value of 'defeated', which must be taken with a grain of salt given that he a) provoked the invasion and b) was swiftly dethroned and held as a political prisoner in Hungary after the Ottomans left Wallachia, leaving his hated brother Radu as ruler]. The Communist block also made a concentrated attempt to show Vlad's cruelty in the post patriotic way possible during the Cold War as documented in Cazacu, Florescu and McNally and other sources.

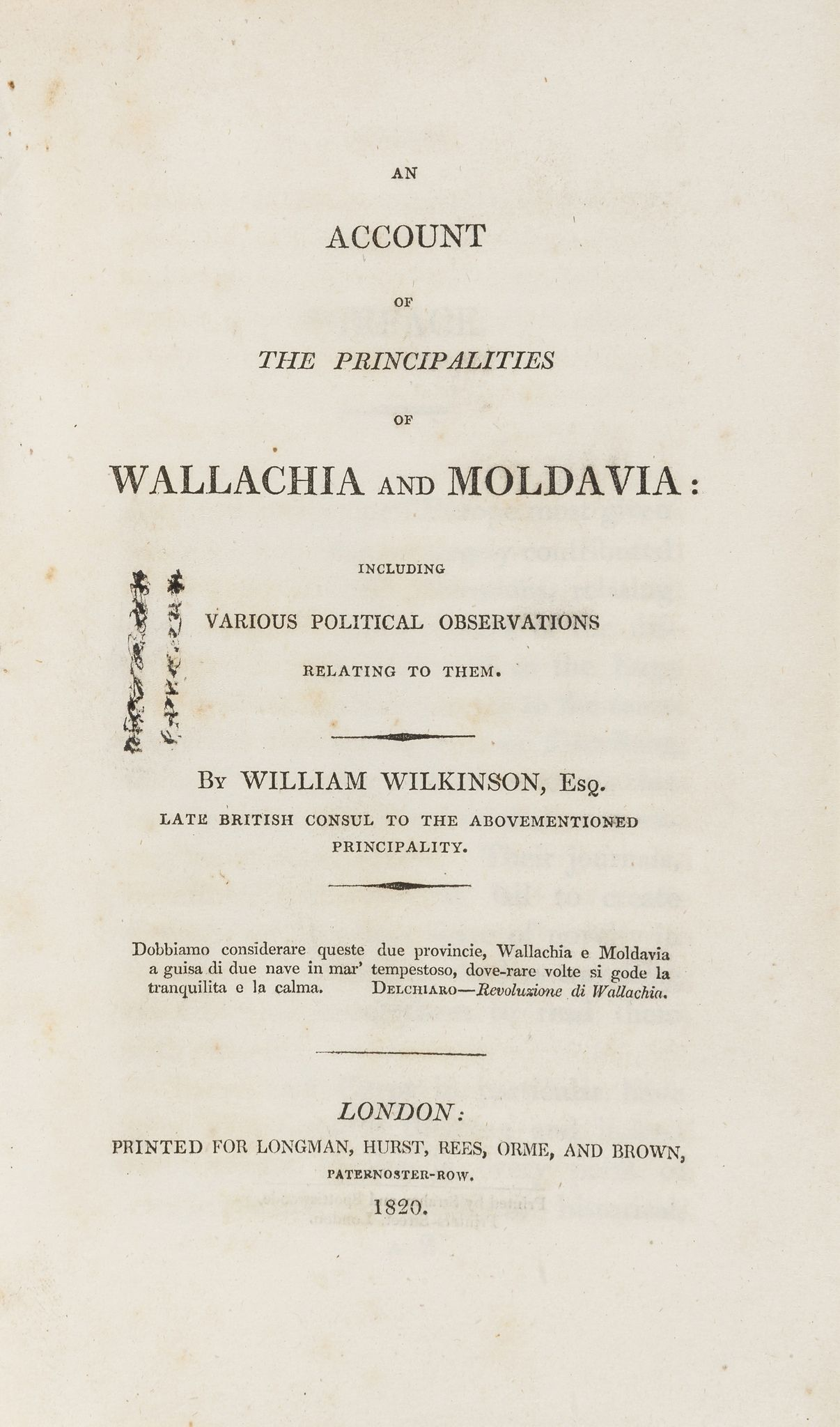

So it may surprise you, given how fraught and variable the figure of Vlad III was in European, Slavic and Romanian mythology and historiography, that Stoker took Dracula's name out of one book.

This book, to be precise:

An Account of the Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia by William Wilkinson.

The research I did seemed to indicate that Stoker did not do a deep dive into the life of Vlad III, the historical figure. Rather, to sum up very briefly what better researchers and authors believe: Stoker took the name 'Dracula' from a single reference in Wilkinson's travel guide, in chief, because it sounded metal. He did do research on the history of the area--and his notes are full of cool lines about local leaders from around Dracula's time and era. One of my favorite quips from Stokes notes on this era reads: "'A lord is a lord even in Hell"--peasant saying from the time of forced labor.'

But as to the particular reign of Vlad III, Stoker seems to have largely avoided or discarded specifics--and used the name Dracula as a starting point for an original character with a name that resonated in the history of the area the novel starts in. Miller, in his work Dracula: Sense and Nonsense sums it up a bit more succinctly:

"This excerpt from Wilkinson contains the only reference to the historical Dracula in Stoker's notes. Nor is there any other information about him in any of the sources we know Stoker consulted. The role of the historical Dracula (Vlad the Impaler/III) in stoker's conception of Dracula has been grossly overstated."

As Stoker's good friend Mark Twain once quipped: "Never let the facts stand in the way of a good story." Certainly, Bram Stoker got creative--and this creativity even extended to how he adapted and portrayed vampires in his work from folklore to his novel. Biswang and Miller, in their annotated guide to Stoker's notes, opine:

"Stoker wisely chose not to burden his vampire with certain folkloric traits, as Paul Barber points out: 'If a typical vampire of folklore, not fiction, were to come to your house this Halloween you might open the door to encounter a plump Slavic fellow with long fingernails and a stubby beard, his mouth and left eye open, his face ruddy and swollen. He wears informal attire--in fact, a linen shroud--and he looks for all the world like a disheveled peasant."

This is all of course a very long way of saying that I was fascinated with the Rosenbach's resources and overall graciousness. My focus pivoted from Vlad Dracula of Wallachia to Stoker himself.

The story I ended up writing (and will be screened on the 30th) was helped tremendously by the Rosenbach Museum in Philadelphia, who are the custodians of Bram Stoker's notes and papers. It was during several days of going through these notes (and the kind help of the research librarians) that I started deviating from my assignment. Stoker himself sort of hijacked my research process--appropriate, given that it was his papers I was going through and not Vlad's (the Rosenbach has an excellent ongoing series called Sundays with Dracula, hosted over Zoom that I heartily recommend).

So I decided to write a story not about Vlad III--but about Stoker's inspirations to write the novel he did, and to put a twist on it. A crustacean twist that absolutely is supported by the documents we have available to us.

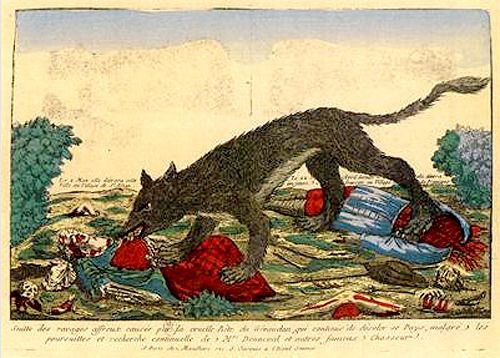

My second announcement (finally brought it all around in the end) is that I'm launching a Youtube series on the Beast of Gevaudan on Halloween!

I don't know how many parts it will end up being, but it'll be my first foray into video-editing. The series will focus largely on the really black comedy of the human response--and errors, and petty grudges--in the wake of mysterious beast attacks that claimed over a hundred people over the span of three years (1764-1767). A good way to think of it is to imagine if your political career absolutely depended on you not only FINDING a killer bigfoot (or similarly elusive cryptid, in this case a wolf/lion/living-fossil/werewolf/witch/serial-killer etc.), but also shooting it while fending off other similarly motivated nobles who want to take your richly deserved limelight! Oh, and some peasants die too, but they don't matter to you.

The videos (and their comments and sources) will also be hosted on this site.