Makhno flees to Paris with his family, and does his best in a bad situation, rubbing shoulders with other anarchists and struggling to make ends meet doing menial tasks. Also, a cameo by Mecha-Stalin.

I would like to thank Sean Patterson, author of Makhno and Memory, for his generous support and kind words over the course of this series. Any mistakes that remain in my videos or writing are entirely my own.

If you want to get some context from the time of Catherine the Great (and her en-serfment policies), the dissolution of the Hetmanate and Crimean Khanate and Pugachev's uprising against Catherine the Great, click here. Or if you like to live dangerously, and fly without instruments or context, continue on ahead without clicking a single link. I dare you.

For a brief history of the Russia Civil War through music click here.

For my previous work on the callous and comically incompetent reign of Alexander Kolchak during the Russian Civil War in Siberia click here.

For the episode where we discuss Nestor's troubled childhood, the Mennonites and whacky assassination antics, click here.

For the episode where we talk about Nestor's return to Ukraine from a Moscow prison and his organizing in his hometown click here.

For the episode covering the horrors of 1918 (along with Makhno's long picaresque journey to Moscow, his daring return and all that I couldn't condense into a fifteen minute talk) click here.

For our customary discussion of sources, we'll begin before Makhno reaches Paris in the year 1926. We're going to focus on the person who first met Makhno in Paris--four years before she does so, in 1922, while Makhno was likely in a refugee camp or jail.

May Picqueray was part of a union embassy to the newly Bolshevized Russia, come to bargain with their leadership for the release of anarchist prisoners. She is treated with every courtesy as part of her delegation, but she realizes as she moves through Moscow she is not free to go where she pleases--the Bolsheviks are curating her experience of their worker's paradise. The Cheka are watching Picqueray, making sure she doesn't see anything she isn't supposed to.

Picqueray grows tired of the Bolshevik's lavish nightly banquets and steals away to visit some of her friends in Moscow. She manages to lose her Cheka 'interpreter' and finds appalling conditions in the Bolshevik capital: widespread poverty and the beginnings of a panopticon-like network of informers. The children of the people she visits are feared to inform on their parents, apparently not an uncommon occurrence. Cold and hunger were the people of Moscow's constant companions, not to mention typhus, the midnight raids of the Cheka and hordes of homeless children, numbering in the millions in Moscow alone.

Picqueray being Picqueray, she swiftly gives vent to her rage at the next cartoonishly opulent banquet filled with Soviet top brass and her own delegation members.

"I clambered onto the table, and to the astonishment of those near me, although not of my comrades, who understood me well, I harangued the delegates who were gorging themselves, telling them how hateful it was that workers' delegates should be stuffing their faces when Russian workers were perishing of hunger. I described the circumstances of those whom I had visited, leaving out the details, of course, and I urged them to make do with meals more in keeping with their status and the circumstances of the country that was welcoming us.

A number of the delegates made their disapproval plain and shooed me away, not that I gave a damn...my outburst had caused a stir and attracted attention to little old me. I was kept under close surveillance and had to be doubly careful."

So May Picqueray has a fiery temperament and doesn't tend to play things close to the vest. At a later point in her visit, during another interminable and overstuffed Bolshevik meal, Trotsky himself asked her to sing something to lift their spirits. Picqueray admits that Trotsky probably expected another recitation of Le Internationale, and, not liking the smug look on his face, decided to do something about it.

She hopped on the table and belted out Le Triomphe de l'Anarchie, a song with the customary French amount of bloody lyrics, which is to say, a lot:

"Arise, arise, comrades in misfortune

The time has come, we must rise up

Let blood flow and redden the earth

But let it be for our freedom!

Standing still is going backwards

The result of too much philosophizing

Arise, arise, aged revolutionary

And anarchy will triumph at last!"

Picqueray adds:

"The face on the communists was a sight to behold. If they could, they'd have gunned me down on the spot."

Here's a link to the song proper--it's something one has to hear to understand the anger and passion in the lyrics. Now imagine you're singing this in a room full of people who have killed or imprisoned people for so much as humming this or glancing at pamphlet espousing anarchist ideas and you get a sense of how goddamn brave Picqueray was.

Trotsky, according to Picqueray's account, didn't flinch at her obvious defiance. He said something to the effect of 'see, you can sing an anarchist song here--there is still freedom in Russia'.

May Picqueray hits Trotsky back with a blistering torrent of words: those who knuckled under to Bolshevik power and adapted were 'free'--but as for the rest, they were bundled off to Burtyi prison [ed. the same prison Nestor Makhno spent seven years in] or off to the Solovietsky islands, like the prisoners she'd come to free, who'd been disappeared last year.

As a final barb, Picqueray asked Trotsky if he intended to make a repeat performance, implicitly daring him to disappear her.

People had been disappeared or sent to gulags for less than nothing, to say nothing of open defiance of the Soviet Government at this time.

(If you guys can't tell, I may have the teensiest crush on May Picqueray).

May manages to snag a meeting with Trotsky within the next week--the Cheka didn't disappear her after all.

Trotsky opens the meeting with an attempted handshake. I'll let Picqueray tell the rest:

"He [Trotsky] rose to his feet, and offered me his hand. Spontaneously, I thrust my hand in the pocket of my jacket and left it there. He turned to Chevalier and bade us welcome. Then he said to me:

'Unwilling to shake my hand, comrade May? Why would that be?'

'I am an anarchist and we are divided by Makhno and Kronstadt [uprising]!'

I was both blunt and imprudent. I was well aware of that, but I was acting on instinct upon finding myself face to face with this mass murderer. In an instant, I grasped the situation and was expecting the worst."

Again, Picqueray says things that other people have doubtless been thinking, but wouldn't dare utter aloud.

After some sophistry (including claiming to be an anarchist himself and insisting that the labor camps and exile to Siberia weren't so bad) Trotsky promised to think about freeing Picqueray's comrades.

It's amazing an icepick got through that slippery bastard's head given the halo of bullshit Trotsky was surrounded by at all times, figuratively speaking. For the purposes of Makhno's story, Trotsky remains distressingly alive and non-ice-picked.

May Picqueray believes that she has lost her gambit to free her friends.

In a surprising twist it turns out May Picqueray managed to get her comrades freed via her negotiations with Trotsky. They catch up to her in Paris some time later.

The reason for this focus on Picqueray is that Picqueray was the person who first interacted with Makhno and his family when he arrived in Paris. May Picqueray got to know Makhno fairly well during his time in Paris when he arrived in 1926, hence my outsized reliance on her account (and using her to give context to the aftermath of the fall of Makhnovia). She describes her first encounter with him in as follows:

"I lived at #120, two minuscule little rooms, but there was always a good broth simmering on the cooker or coffee ready for serving. Indeed, it was my 'privilege' to welcome the waves of immigrant comrades arriving from pretty much all over back then: the Russians fleeing from dictatorship, the Bulgarians likewise, the Italians who managed to dodge Mussolini's castor oil and prison. After being restored, they would be directed by me to the home of this or that comrade who had a room or a bed, or some corner where they might rest, be it in Paris, in the suburbs or out in the countryside.

It is in this way that one morning a couple showed up with their girl, all three worn out and disheveled. Especially the man, whose entire body was covered in wounds. They had some refreshment and stretched out on the only bed where they very quickly dropped off to sleep. I sent for a comrade who knew Russian, whereupon I discovered that my guest were Makhno, his partner Galina, and their daughter. I was greatly moved in the presence of the 'great man' whose epic I knew only from hearsay, epic, the word is not to strong a description of Makhno's exploits. I listened to him talk for nearly an hour, but, realizing he was very weary, I entrusted him and his family to some friends in the suburbs took him in and where a doctor offered him the care he required for his condition."

Picqueray also offered her opinion of Makhno--an earnest fellow out of his element, basically good at heart. She wasn't the only person who thought of Makhno in this way--indeed, Makhno's reputation had reached across the world as early as 1922. If you'll permit me to dash back to 1922, we'll be united with an old friend: Osugi Sakae, and his near miss with the Makhnovists and Makhno.

Osugi Sakae, a Japanese anarchist, writer and philosopher, arrived in Paris in 1922. He was a polyglot and a fascinating character in his own right (expect to hear more from me about his life and work further down the line). He managed to fool his constant police tails by a Ferris Beuller-like ploy (feigning sickness with a dummy and fleeing the country for Europe). Taisho Japan was not a friendly place to be left of anything short of a right-wing hyper-nationalist. I will talk about this at length in my work on Osugi, but the casual way he mentions routinely evading his police surveillance teams reminds me of how someone would matter-of-factly mention taking off their shoes or jacket--just a fact of life for him, something done everyday. Having escaped Japan, Osugi toured France and tried to enter Germany. According to an article on Osugi's visit to Europe, he had other motives:

Sakae's biographer, Thomas A. Stanley, further elaborates on Sakae's fascination with Makhno and the Makhnovist movement in his work:

"...and although Osugi did not know his [Nestor Makhno's] whereabouts, he knew that Berlin was a gathering place of many of the former guerrilla army leaders, including Voline, one of Makhno's major political advisors. Osugi never met these men, but he did collect materials on Makhno, materials he used to good effect against the Bolsheviks in Japan. He also met some of the Russian emigres in Paris and heard directly from them about conditions in Russia and the methods of the new government."

Osugi wrote about Makhno himself saying, among other things:

"Thus the meritorious service of Makhno and the Makhno movement to the Russian Revolution was in fact great. Most of the various counter revolutionary armies and invading foreign armies [that occupied] most of European Russia was driven away by them. You almost cannot conceive of even the establishment of the Bolshevik government without them...Makhno the anarchist did not build the Makhno movement: the revolutionary rebellious movement which was based on the instinctive self-defense of the Ukrainian people, simply hunted Makhno up."

Stanley adds his analysis of Osugi's perception of Makhno:

"Fortunately, Makhno's character fit the requirements of the movement and, equally fortunately, so did his anarchism, although Osugi might have added, propagandistically, that it would be only natural for an instinctive movement of the people and anarchism to meld perfectly with the other. This, then, was "the single greatest lesson that the Russian Revolution could teach us."

If Osugi had managed to a) stay in Paris for four more years and b) never return to Japan, there was a non-zero chance he could have met Nestor Makhno in person. There's a fun bit of alternate history for me to ponder. As it was, Osugi was forced to return to Japan, where he met his end in 1923 in the Amakasu Incident.

Even though the Free Territory of the Ukraine no longer existed, Makhno remained an example for insurrectionists, syndicalists, anarchists and people who hated oppression everywhere. Old Makhnovites turned up all across the world, but most prominently in the Spanish Civil War.

Makhno also got to know Alexander Berkman and Emma Goldman during his time in Paris, famous American anarchists who had been some of the first into Bolshevik Russia--and came away horrified. Berkman wrote a stirring essay on the subject of Bolshevism, entitled: "The Russian Tragedy" where he outlines the many failings of the Bolshevik state (repression, consolidated power, in contrast to its slick PR-campaign as a worker's utopia, to name but a few things). Both Berkman and Goldman had been expelled from American soil for their political beliefs--and were even more disappointed in Bolshevik Russia, if that were possible.

Ida Metts, another friend of Makhno in Paris in particular, had some pointed words reserved for Mrs. Makno, Agafya Kuzmenko. Here's one particular gem from her remembrances:

Makhno's written responses to Bolshevik slanders (particularly against the charges of anti-semitism) were direct and to the point, written and spoken during his last years in Paris. These writings involved parrying everything really outlandish attacks (like massacring, of all things, a troupe of wandering dwarves which appear nowhere else in anyone's narrative) to political polemics. This was complicated by the fact that several former anarchists in the Black Army (prominently, Belash and Chubenko, according to Patterson's work) wrote histories of the Makhnovist movement that showed Nestor in the worst possible light--under pressure from the Bolshevik government, specifically the Cheka.

The Bolshevik government did its best to either discredit and blacken Makhno's legacy or to unperson him, as Catherine the Great had attempted to do with Pugachev centuries earlier.

Certainly, the history of Russia and its satellites in the twentieth century is a litany of atrocities. The Bolsheviks used words to mean the opposite of their definitions, weaponized semantics and committed horrific crimes to entrench the power of a few entrenched revolutionary vanguards that had no problem pulling the ladder up after them. This did not escape Makhno's notice, he excoriated the Bolsheviks for this several essays, particularly in their brutal suppression of the Kronstadt revolt, already mentioned above by Picqueray.

For context, the sailors at Kronstadt had the temerity to demand what the Bolsheviks had promised and the sailors had worked so hard for in the revolution--workers unions (soviets) collective ownership, civil rights and freedom from the Bolshevik bureaucracy. The Bolsheviks under Trotsky ultimately crushed this rebellion by the sailors--there is some thought that the sailors pulled their punches in hopes of negotiating with the Bolsheviks, and that hesitation cost them dearly. Makhno writes:

Otto Ruhle, to name another prominent critic but writing after Makhno's death, wasn't shy about what the Bolshevik government became after the Russian Civil war, writing an essay entitled "The Struggle Against Fascism

Begins with the Struggle Against Bolshevism" (1939) which is exactly what it says on the tin and worth a read if you have some spare time.

There should be no doubt that Leninism led directly and logically to Stalinism--a difference of scale of action and not ideology. This was only possible through the massive repression, purging and massacre of all opposing political ideologies. The massacre at Kronstadt, Tambov, the Holodomor in Ukraine, Stalin's purges and interference in the Spanish Civil War, these are all things in keeping with Lenin's playbook only applied to a wider stage.

The last years of Makhno were not happy ones. He was like a graft or cutting from a plant, struggling to adapt to a new ecosystem. He worked menial jobs--as a janitor or assembly worker for a Renault-plant-- for little renumeration and his health suffered dramatically. The one point of happiness seemed to be his little daughter Yelena, who according to all sources on the subject available, he doted on.

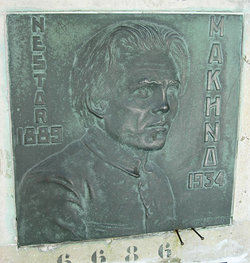

All in all, Nestor Makhno was not cut out for a life that wasn't that of a Ukrainian farmer or revolutionary. He died unhappy, of tuberculosis, in 1934. He remains were buried in Paris, far from Ukraine.

His family did not fair well after his death--they fled the Nazis back into the Soviet Union, were sentenced to years in a labor camp and ultimately settled in Kazakhstan.

Nestor Makhno remains venerated by anarchists, demonized by Leninists, Stalinists and Trotskyites, and remains something of a mixed bag historically. Certainly Makhno had ideals and principles and largely stuck to them (which set him apart from many other revolutionary leaders) and attempted to instill those same values (and limits) on revolutionary violence in the Ukraine, to some effect but not enough to dampen the horror of the Civil War. Justice became terror. Expropriation became massacre, even if that may not have been Makhno's intention. I'll let Sean Patterson's work on Makhno speak for me here and while I have used this quote in previous segments, I believe it bears repeating here in the final accounting:

"Revolutionary terror emerges from a context of extreme reciprocal violence and is ostensibly based on the pursuit of 'justice'. In a revolutionary situation, this frequently occurs when the state can no longer maintain its monopoly over violence. Violence becomes decentralized and legitimated through competing local forces. Historian Arno Meyer writes: 'The quantum jump between of violence is both cause and effect of the breakup of a state's single sovereignty into multiple and rival power centres, which is accompanied by a radical dislocation of the security and judicial system. As a consequence, the positive legal standards for judging and circumscribing acts of political violence give way to moral and ethical criteria. In other words, in the calculus of means and ends, the principles of 'law' are superseded by those of 'justice'. Due to the disappearance of universal law as administered through the state, justice is subjectively applied according to each competing power. These competing notions of justice come into conflict, triggering, as in the case of Makhno and the Mennonites, a state of escalating violence in which each group attempts to use force and fear to compel the enemy to accept their regime. In this scenario, the moral line between justice and terror begins to blur."

It would be reductive and wrong to view Nestor Makhno's role in the Russian Civil War as wholly positive, just as it would be to view it as wholly negative.Revolutions can be brutal, and the Russian Civil War was particularly savage. Patterson further observes that many people joined Makhno's movement, not out of sincere devotion to anarcho-communist principles, but to help settle old scores with their enemies which complicates matters quite a bit. I would add that this vengeful tendency was further fed by the history of land-hunger and economic inequality that had been endemic since the time of Catherine the Great and serfdom, which helped feed the movement (and later veneration) of Pugachev.

A reminder of this caught me as I was finishing up this blog--I was double checking where Makhno was buried in Paris. There is a website for that, because of course there is, and a digital service for leaving flowers at the grave of the person in question. The first one under Makhno's grave read simply: "He murdered my grandparents."

When you lose track of the faces of the dead, it becomes far easier to make people into devils or angels.

This isn't only a Makhno thing. The whole ugly edifice of great-man history as defined by Carlyle rests on a foundation of moldering corpses and selective memories. Napoleon was nowhere near as magnanimous or brilliant as he believed himself to be, for example, and ruthlessly clamped down on both free enterprise and the free press during his reigns over France--but is idolized by Francophiles and military history buffs the world over. Thomas Jefferson repeatedly raped his slave Sally Hemmings, and George Washington pursued the most legalistic way possible to keep the maximum number of his slaves under his employ while he lived. Yet US nationalists believe these figures to be near demi-gods of moral virtue whose words are sacrosanct and unalterable. Even people who would describe themselves as political moderates bristle when one suggests that any of these figures they've elevated had so much as a crooked toe.

Winston Churchill knowingly embraced policies that starved 3 million Bengalis, to say nothing of the concentration camps in Kenya that methods out of the Nazi playbook less than a decade after WWII, yet Churchill is praised through the western world and his dark side swept under the rug to sell memorabilia and merchandise.

We won't even deal with the worshippers and fanboys of Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Mao, Hitler, Mussolini, Franco or Trump on the grounds that they are not serious people and are beneath contempt. Those figures so obviously added far more to the total sum of human misery that no possible benefit can balance it out.

Heroes are for mythology--to teach lessons in an abstract way. We can idolize Odysseus, Beowulf and Junie B. Jones because they never drew breath in our world. Heroes live in our minds and art and folklore, engaging in contradictory adventures and timelines. Contrariwise, all historical figures for our purposes were human beings, with all the attendant flaws and virtues. To reduce a human being to a metronym (to borrow a term from Patterson) does both a grave injustice to truth, nuance, and at core, reduces a person to a thing, always a monstrous act regardless of context. By understanding and examining the stories told about historical heroes, we can learn more about the storytellers and their perspective--though not necessarily as much as we would like about the person the story purports to be about.

On the lighter side, I'm about to read Steel Tsar by Michael Moorcock, where I'm told Makhno gets to nuke Tsar Stalin in an alternate universe (I'll write a review of it when I finish reading it).

For a short man, Nestor Makhno cast a long shadow across world history. I've struggled writing this last blog in the sequence, but I can reassure myself knowing I can always come back to the research I did on Makhno and the friends I made along the way. There are a thousand and one sub-blogs and essays to write about this man and era--the role of charismatic leaders, idealists, politics, the strain of having principles in a brutal time, the human costs of revolution as opposed to the quiet grinding of the status quo, the cultural iterations of charismatic leadership--and I will visit him again.

More soon! If you like what I do, subscribe to my mailing list below. That way you'll be the first to know when something knew pops up--and I do have big plans for October.

Here's my Q and A with Sewer Rats!

World History With Charlie Episode 7 Q & AFeel free to post your questions in the comments section!

Posted by Sewer Rats Productions on Thursday, October 8, 2020