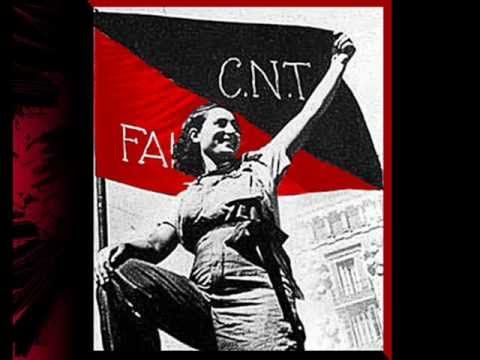

A las Barricadas is a famous song from the Spanish Civil war celebrating the worker's revolution against the attempted fascist coups in 1936 and bloody civil war that followed. It was, in particular, the song favored by the Spanish anarchist organization CNT-FAI.

We're going to be studying the song's history, the history of popular uprisings (especially when it comes to barricades from the 18th-21st centuries) and how it is viewed now. We'll be talking a long and meandering look at the history of this song--following the historian's tradition of taking a long wind-up before actually arriving at our topic.

1) On the topic of Barricades

But first a word about barricades.

If you are familiar with barricades, it's likely because you love history or you saw Les Miserables at some point, specifically this song:

I'm not a scholar of the French Revolution but a lasting legacy of the revolution was a realization of how powerful the citizenry were when roused.

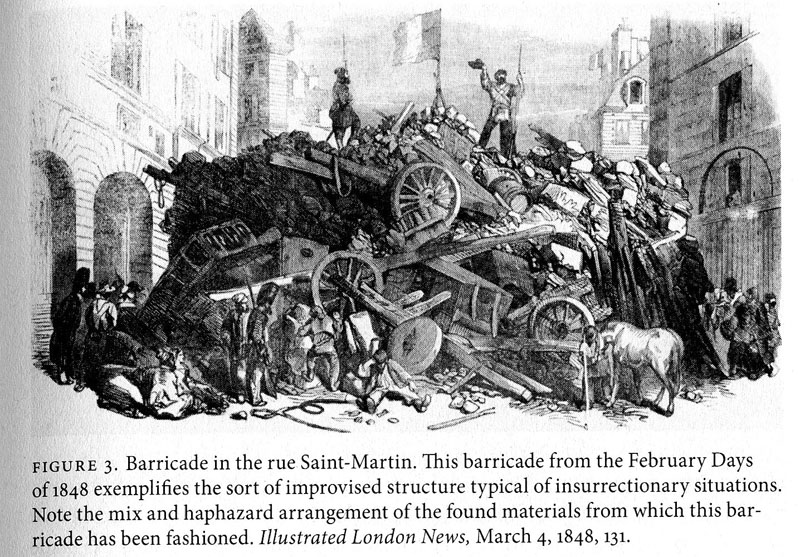

For the longest time, there wasn't really a counter to coordinated and systemic use of barricades in an urban environment. It was the dominant strategy for urban warfare and the military, largely, was helpless against it. The narrow streets, the winding paths and the close-knit cohesion of neighborhood created an atmosphere ripe for ambushes against government or military forces that tried to venture into the neighborhoods to dismantle the barricades.

The prospect of barricades in the Parisian streets gave Napoleon nightmares, and was always, doubtless, a thing lingering in the hindbrain of anyone who had to rule France--that the people could alway get sick of them, and if the discontent reached critical mass, there wasn't a damn thing they could do about it save by drawing on extensive military force to quell a restive populace--an expensive and bloody measure.

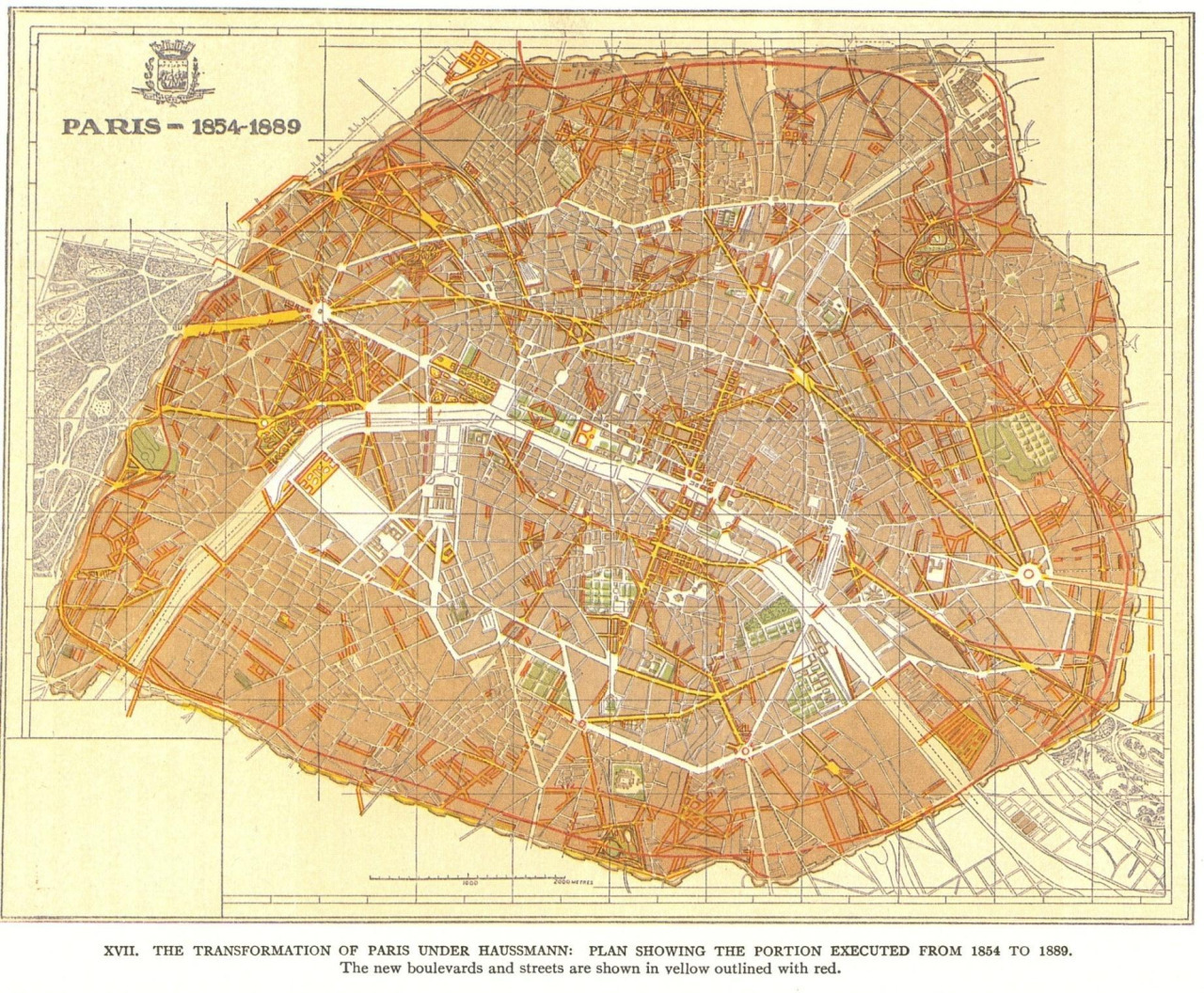

So the counter to the barricade was to atomize the city. In short: destroy the neighborhoods that made the barricades possible. James C. Scott, in his indispensable work, Seeing Like A State details the efforts of the French government to standardize something as seemingly mundane as road width--enough to drive a cart full of soldiers across, for example. I'll let Scott speak for himself here:

"At the center of Louis Napoleon's and Haussmann's plans for Paris lay the military security of the state. The redesigned city was to be, above all, to be made safe against popular insurrections. As Haussman wrote: "The order of this queen-city is one of the main conditions of general [public] society." Barricades had gone up nine times in the twenty-five years before 1851. Louis Napoleon and Haussman had seen the revolutions of 1830 and 1848; more recently, the June Days and resistance to Louis Napoleon's coup represented the largest insurrection of the century. Louis Napoleon, as a returned exile, was well aware how tenuous his hold on power must prove...

"As Haussman saw it, his new roads would ensure multiple, direct rail and road links between each district of the city and the military units responsible for order there...Explaining the need for a loan of 50 million francs to begin the work, Leon Faucher emphasized state security needs: "The interests of public order, no less than those of salubrity, demand that a wide swath be cut as soon as possible across this district of barricades."

To sum up: the French government was leery about its chances if the barricades went up again, and so modified the roads and infrastructure of Paris specifically to allow speedy deployment of force to anywhere in the city, which at the same time destroyed the neighborhoods and geography that made the barricades so damned effective. This isn't just theory, either--Haussman's work was validated by the crushing of the Paris Commune after the latest Napoleon had a streak of bad luck and the barricades went up then fell to the French army.

The majority of modern cities take their cues from Haussmann's ideas about uniformity of street width and destruction of close-knit neighborhoods (see what Robert Moses did in New York, for example, as documented by Caro).

The modernist city-scape can be said to be as much about preventing popular uprisings as it is to providing utilities and shelter to its citizens, seen from this perspective.

The cities that the majority of us in America and Europe live in are deliberately atomized in such a way so as to make a popular rising against state or local governments as difficult as possible.

Anyway, the reason for this tangent is to remind the reader that going forward, calling for going to the barricades is an inherently revolutionary one, a summons to action, to remake society--social revolution. This brings us to the actual origins of the song in question.

2) Name's the Same, but nothing else is: Warszawianka (1831)

The tune for A Las Barricadas actually comes from a Polish song, Warszawianka. Confusingly, there are two popular songs with this title with notable places in Polish history, the first of which which was a staunchly anti-Russian empire song that shares no rhythms or lyrics with the second, the one that actually went onto inspire A Las Barricadas. You can listen to this first version here:

The song is worth taking a minute to examine in its own right. This first version featured prominently in the Polish 1830-31 uprising against Russian imperialism, featuring lyrics like:

"To horse, a vindictive Cossack calls!

Punish the mutinied Polish companies!

Their fields have no Balkans,

In a trice we shall crush the Poles a sort

The Polish rejoinder in the chorus to this slight is unambiguous and defiant:

This breast will stand for the Balkans

Your tsar vainly dreams of loot

From our enemies nothing remains

On this ground, except corpses."

The song also explicitly cites French revolutions as inspirations for their own national liberation (first stanza), which I think makes sense, given the tensions of the age.

The November uprising wasn't a success, but the enduring legacy of the song is that it is now, apparently, the official song of the Polish military.

Man, one of these days I'm going to make a dedicated database of all popular media that started out as ways to tell the Russians to get bent. I'm certain it will be exhaustive. This wasn't the last rebellion on Polish soil, not by a long shot, which leads us to...

3) The actual song, Warszawianka (also called "Whirlwinds of Danger") 1905

Anyway, this anti-imperialist, Polish-nationalist song proved to have such appeal that it's title was adopted by the burgeoning socialist movement in Poland (1905-1907). Thusly it is called "Whirlwinds of Danger". You might recall from my Nestor Makhno series that the first (aborted) Russian revolution took place in 1905, shaking the Slavic world nearly to pieces. It laid the essential ground work for multiple rebellions and eventual Bolshevik coup in 1917, and saw a surge of anarchist, socialist and labor unions trying to break free of Imperial Russian rule--from the Ukraine to Poland to Moscow.

Sadly, the empire managed not to fall apart just then and the backlash was vicious. In Poland, the Socialist parties led the resistance, and used this song to rally their comrades.

There are multiple versions of this rallying call--notably, the Communists noted what a catchy little ditty it was and promptly appropriated it. However, the opening lyrics of the socialist version bear some examination:

"Whirlwinds of danger are raging around us,

O'erwhelming forces of darkness assail,

Still in the fight see advancing before us,

Red flag of liberty that yet shall prevail."

This would be adapted later into the CNT-FAI's trademark anthem, which would not only borrow the lyrics in part, but also the tune.

4). Spain 1936, Spanish Civil War Begins (Alas Barricadas)

The three-year long Spanish Civil war is a complex topic worthy of deeper writing than I will have time or space to do here. So a general picture will have to suffice of the ground at the start of the war.

The Catholic church and the landed gentry had enjoyed more or less unlimited power in Spain for generations, with only a few hiccups. The Catholic church discouraged literacy, any number of legal reforms, and basic healthcare measures for the peasants and workers of Spain.

George Orwell quipped in his book Homage to Catalonia that he believed General Francisco Franco didn't start his coup (that led to the Spanish Civil War) with the intent to impose fascism upon victory--rather, he started with the intent to restore Spanish Catholic feudalism and grew more and more fascist as the war dragged on.

At any rate, the Catholic church was a major regressive and anti-human rights force in Spanish life, and turned those tendencies into political and economic clout. They chose to throw this clout they behind conservatives and fascist groups, to the surprise of literally nobody who is remotely familiar with Spanish history.

Against the Catholic church and the conservatives stood the liberals, some members of the gentry and most notably for our purpose the socialists, communists and anarchists (in particular the CNT) in stout opposition.

Spain had just emerged from a period of dictatorship under Miguel Primo de Rivera (1923-1930) into something like a republic, something that made the authoritarians more than a little nervous.

The Spanish anarchists of the CNT bear special mention here--they had something that Makhno's Free Territory of Ukraine lacked, that is to say, a dedicated anarchist tradition going back six decades at all levels of society. Or, as Murray Bookchin put it in the forward to The Anarchist Collectives:

"The Spanish generals started a military rebellion; the Spanish workers and peasants answered them with a social revolution--and this revolution was largely anarchist in character...what made the Spanish Revolution unique is that workers' control and collectives had been advocated for nearly three generations by a massive libertarian [Anarchist] movement...owing to the scope of its libertarian social reforms, the Spanish Revolution proved not only to be more profound (to borrow Bolloten's phrase) than the Bolshevik revolution...indeed, in many respects, the revolution of 1936 marked the culmination of more than sixty years of anarchist agitation and activity in Spain." [Emphasis mine]

Indeed, we would be remiss not to mention Fanelli, Salvochea, Ferrer (founder of the Modern school) or any of the other foundational anarchists who spent their lives establishing Spain as an anarchist stronghold.

At any rate, in 1936, the conservatives and fascists ran in an election against literally everyone else.

They lost--the Republicans (as they would come to be called, including the CNT, the liberals, the communist UGT and socialists etc.) triumphed.

So naturally the fascists, the Catholic church and military received their loss with good grace and decided to work hand in hand with their enemies to build a more just and peaceful world.

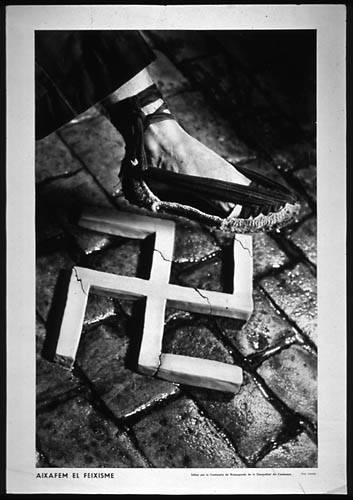

Haha, no. No, the fascists (then as now) showed no respect for any form of democratic process and launched a coup attempt.

General Francisco Franco led the attempted military coup after a close national election in 1936 where a coalition of liberals, socialists, anarchists and communists narrowly triumphed.

The majority of Spain's military went with him Franco and the other generals. The fascists stormed government buildings, took officials hostage and set up light artillery and machine gun nests in the streets.

The people of Spain--largely under the aegis of the red and black flag of the CNT-- went to the barricades.

In Catalonia, and Barcelona in particular, the anarchists were the leading faction in thwarting Franco's initial power grab.

A Las Barricadas had travelled for decades and from the lips of countless people to become the CNT's anthem. From a Polish nationalist song about throwing off Russian oppression, it had transformed into a song about overthrowing oppression everywhere, for everyone.

The opening lyrics still carry strong hints of the 1905 version of Warszawianka:

Black storms

shake the sky

Dark clouds

blind us

Although death

and pain await us

Against the enemy

we must go

The most precious good

is freedom

And we have to defend it

with courage and faith

Raise

the revolutionary flag

Which carries the people

to emancipation

According to the Movement podcast's account of the opening months of the Spanish Civil war, the people of the cities--individually, and in the form of anarchist-led people's militias rose up against the fascist coup attempt.

Working-class people charged entrenched positions with nothing but their bare hands or grenades picked off of dead fascist soldiers. Taxi drivers used their cars to ram fascist machine gun nests.

Franco's attempted military coup was foiled in the majority of Spanish cities.

The fascist coup attempt in Spain failed--the next step was an all out civil war.

To the anarchists, the social revolution and the fight against fascism were indistinguishable and not discrete events. The liberation and freedom of women and the working class were priorities.

For a good while, major cities like Barcelona were run in part or by the majority anarchists, specifically the CNT. The anarchist collectives abolished authority (save for workers councils, organized by workers) and took control of major infrastructure, in many cases increasing productivity and efficiency, such as the case of the train-systems and post-office.

George Orwell, who arrived in Barcelona in after the thwarted coup, joined up with the POUM, a Trotskyist group, but kept careful notes and observed the anarchist military training and social organizations closely.

"It was the first time I had ever been in a town where the working class was in the saddle. Practically every building of any size had been seized by the workers and was draped with red flags or with the red and black flag of the Anarchists; every wall was scrawled with the hammer and sickle and with the initials of the revolutionary parties; almost every church had been gutted and its images burnt. Churches here and there were being systematically demolished by gangs of workmen. Every shop and café had an inscription saying that it had been collectivised; even the bootblacks had been collectivised and their boxes painted red and black. Waiters and shop-walkers looked you in the face and treated you as an equal."

We could go into the CNT-FAI a good deal more, but this is where we will hold for now. There is a complicated history of the group and anarchism in the context of the Spanish Civil War (and resistance under the rule of Franco), that is well worth another series. I think a brief zoom-out to the greater context of the Spanish Civil War would help underscore my final point which leads me to...

5. No Pasaran (1936-1939)

Songs were plentiful through the course of the Spanish Civil war--marching songs, rallying songs, mourning songs, battle songs. The most famous of them all--indeed, a Republican song rather than an exclusively anarchist, social revolutionary one. No Pasaran was born at the beginning of the three long Siege of Madrid, held by Republican forces against the fascists.

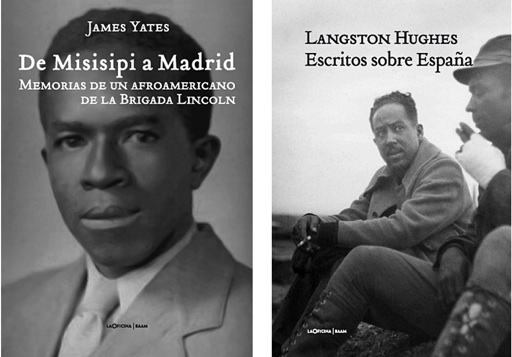

"No pasaran" roughly translates to "They will not pass" and was wildly popular in its own time. The Siege of Madrid became a worldwide point of interest, and the phrase (and song) achieved worldwide popularity. James Yates, an African-American volunteer in the Abraham Lincoln Brigades fighting on the side of the Republicans, wrote in his memoirs that by the time he arrived in Spain in 1937, the phrase had already become a Republican battle-cry:

"We finally pulled into the station and voices singing "The Internationale" greeted us. Every nationality in the world seemed to be represented in the delegation pressing toward the train. We joined in the singing as did a few of the refugees that had found their way to the station. I felt an overwhelming sense of kinship with all the people around me. As a song finished, we applauded vigorously and shouted "No pasaran!" Lovely girls gave us flowers."

Madrid held out against the fascists for three long years, only falling at the end of the war. The song (and phrase) still live on as an anti-fascist song, long after Franco's death.

6. A Las Barricadas (2010)

The final thought I will leave you with is our sixth song--one you've heard before, and this blog is about. But this is a recording made in 2010, in Spain, uploaded to CNT-affiliated Youtube channel. Franco's holocaust and reign of terror lasted for decades after the Spanish Civil war, and Spain as a whole never really reckoned with the decades of fascist rule in an organized way (the phrase in Spanish is 'Pacto del olvido'--literally, 'pact of forgetting') which has greatly hindered Spain's ability to come to grips with or accept the horrors of it's fascist past.

Still there is something cheering in watching a chorus of people, belonging to a political party that was once nearly eradicated and who grew up in a fascist state (or it's aftermath) singing these words, imagining a better world and spitting in the teeth of fascism:

Working people march

onwards to the battle

We have to smash

the reaction (or "reactionaries")

To the Barricades!

To the Barricades!