This is not an exhaustive summary or analysis of the Years of Lead but it should serve as an introduction to their beginnings.

And like any good fan of history, there will be a bit of a wind-up to reach our destination, so strap in.

The reconstruction and restructuring of Europe post WW2, in American discourse and education, is generally limited to either talking about the Marshall Plan, the Berlin Air Lift, and such high points. How it actually went was much uglier.

In short, the agenda of the countries of Europe after WW2 (except Francoist Spain, which avoided an invasion and um...regime change by Franco rebranding himself as an ardent anti-communist rather than as a fascist, though of course he was as fascist as ever and continued merrily genociding away) was both to restore what had been lost during the chaos of WW2. That meant a lot of the old, oligarchical social order in a large part.

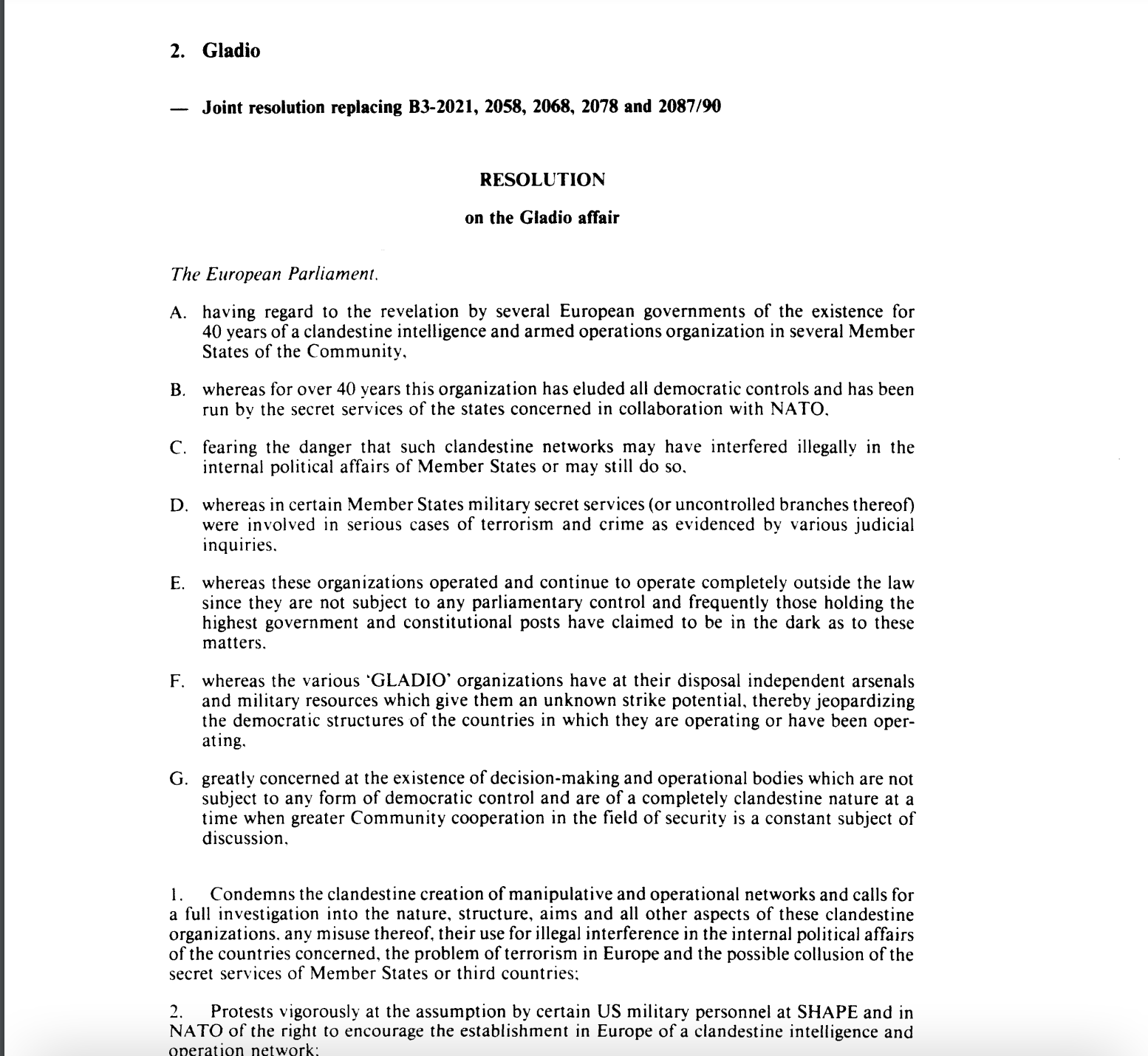

The example of Franco is illustrative, as many fascist groups and tendencies billed themselves as anti-communists to get funding to push back against progressive movements. This funding came from a wide variety of groups, but among the donors were NATO, the American CIA and British MI6 in various capacities. The exact details of this material support for neo-fascist gangs is beyond the scope of this particular blog, but I would point you towards Operation Gladio. In short, it was a NATO funded sponsorship and encouragement of right-wing terror groups, with the nominal goal of waging war on the USSR if it conquered Europe, but with the practical effect of targeting left-wing policies in fledgling democracies and hastening authoritarian tendencies in the host countries.

It was formally acknowledged by NATO in 1990.

Throughout Europe, the threat of communism was used as an excuse to push back on civil, economic and political rights, and nowhere more so than Italy. In northern Italy in particular, the fear of workers unions and expanded civil and economic opportunity motivated violent repressions by the 'moderate' democratic government, corporations and neo-fascist groups. Writing in 1964, the Italian historian Barzini said of his countrymen:

"The rich and powerful are naturally afraid for their fortunes, privileges, honored positions in society, and often enough, for their lives. They are so timid and insecure that most of them are always tempted to follow a demagogue who promises them solid and enduring security...the fear of the rich is nothing to that of the poor. They have no protection, no private armies, no treasures at home or abroad, no palazzi, no influential friends. They have nothing but their miserable jobs and their lives to lose. They do not like the way things are run and have been run for a long time, but they are also frightened by change."

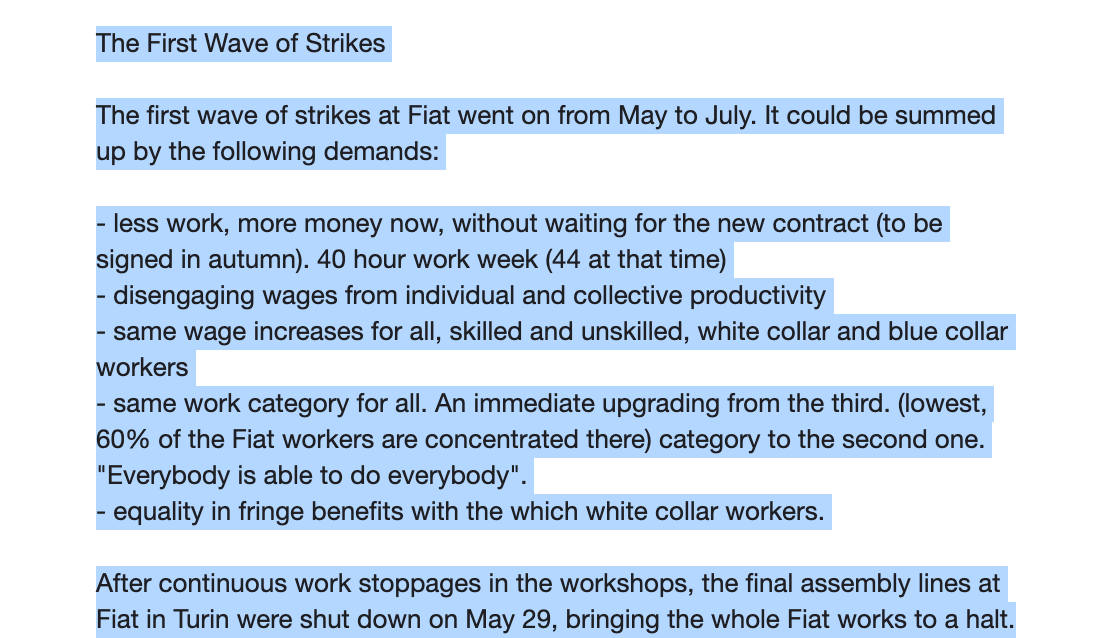

That fear wore off eventually, as conditions became intolerable for the working classes. Anti-capitalist workers unions formed, most notably for our purposes, Potere Operaio ("Worker's Power", 1967-1973) and held strikes and demonstrations. Operaio had the double misfortune of having to fight the old entrenched unions of the industrial sector (who largely had what they wanted and were leery of any sort of change from the bottom) and management itself. From a 1970 Potere Operaio document, we can see that at the start their demands were modest, but management refused them even those concessions.

On an incidental note, Potere Operaio had one of the absolute best rallying songs of the period. Or maybe I'm just a sucker for any song that starts with a whistle. Take a listen:

The lyrics read in part (for those not fluent, or even conversant, in Italian, like me):

State and Masters, be careful,

the insurrection party is born;

Workers ' power and revolution,

red flags and Communism will be.

None or all, or all or nothing,

and only together we must fight,

rifles or chains:

that is the choice that remains for us to make.

It is this atmosphere of unrest and the attack on capital that the strategy of tension was employed--in many ways, but the one that changed the intensity of the struggle occurred in Milan. At the agricultural exchange, of all places.

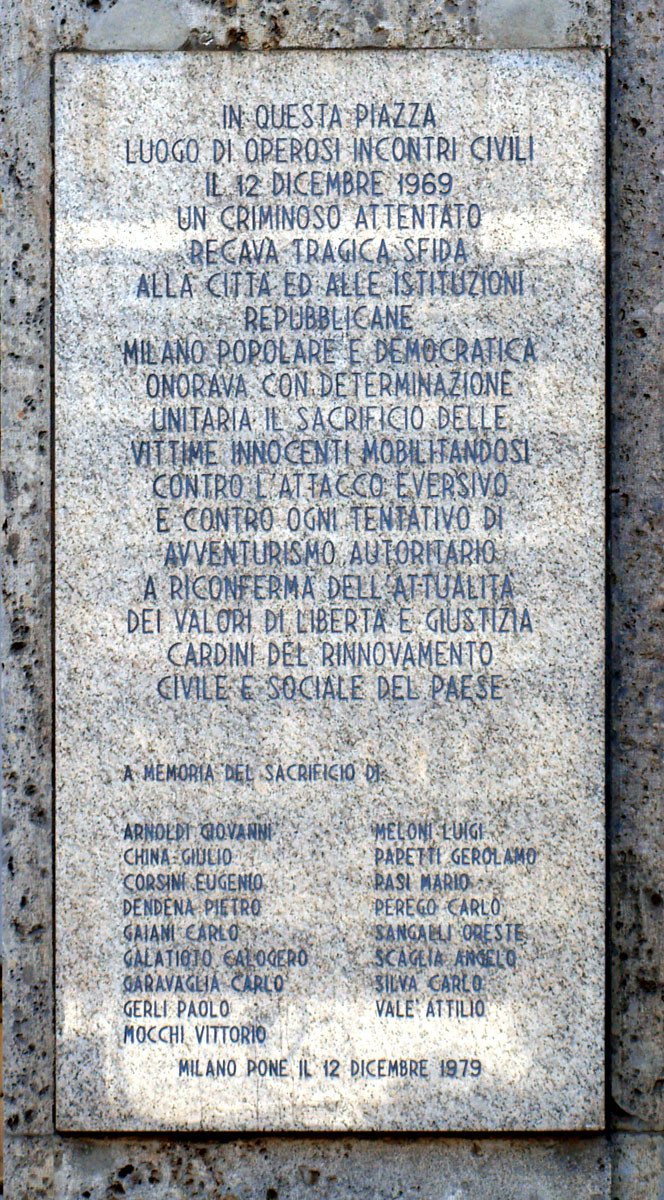

December 12th, 1969. A bomb went off in the Piazza Fontana, Milan, killing 17 people and injuring 88.

According to a write up from the Guardian in 2015 summarizing the importance of the Piazza Fontana bombing:

Indeed, this was part of the Italian government's 'strategy of tension' which is a very nice way of describing the following process:

1. Bomb and terrorize your own citizens using a mix of police officers and neo-fascists.

2. Blame the anarchists, socialists, labor unions and communists, anyone agitating for better pay, civil rights, or against the return of fascism to Italy. Arrest or execute them 'in connection with the bombings'.

3. Progressively strip away civil liberties in the name of security while attempting to crush the progressive movement in your country with help from Franco's Spain, the American CIA and British MI6 and NATO. Make sure your police forces coordinate with the neo-fascists and even help them flee the country if they are somehow arrested or turned state's witness. Spain likes fascists, hide them there.

4. Repeat as necessary.

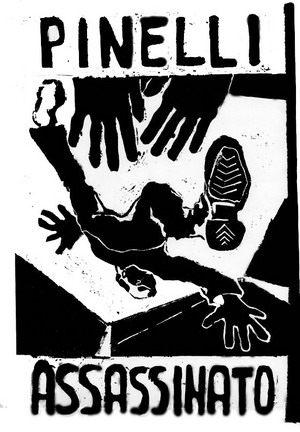

Acting with nearly supernatural speed, the Milanese police swiftly blamed the local anarchists and arrested two of them, Valpreda and Pinelli, with no supporting evidence whatsoever.

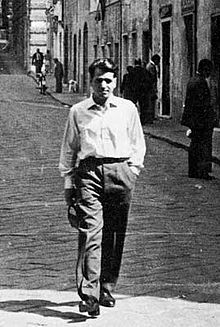

Pinelli was a member of the Anarchist Black Cross (which sounds sinister, sure, but it is easier to think of it as an anarchist-specific variant of the Red Cross that focuses on prison relief and activism). It is a venerable institution, even our friend Nestor Makhno organized new Anarchist Black Cross chapters during his struggles in Ukraine earlier in the 20th century.

Pinelli was active in anarchist circles and even founded a few discussion groups and local activist chapters personally (including the Sacco and Vanzetti anarchist society in 1965, named after two Italian anarchists framed and executed in America). He met his wife at an evening Esperanto class (I swear one day I'll do a blog on constructed languages like Esperanto and anarchism).

To zoom out a bit: As you may have gathered, Italy has a long anarchist tradition. From the soaring works of anarchist lawyer/poet Gori to the famously fractious and erudite Malatesta, Italy was one of anarchism's first strongholds after Bakunin split from Marx, along with Spain.

Around 1894 following the assassination of French President Carnot by Sante Caserio in retribution for the execution of anarchists (which deserves attention in its own blog), Gori along with other Italian anarchist refugees were expelled from France and Switzerland. During his brief imprisonment, Gori wrote "Addio Lugano Bella" (Goodbye Beautiful Lugano), which became a staple anarchist anthem:

Pinelli, like Gori generations before was held for three days by the police and interrogated throughout.

Unlike Gori, Pinelli was interrogated by three officers and a short time later, he was fatally thrown from the window of the police station. From the fourth floor.

The police suggested it was an accident of interrogation, perhaps he fainted near the windowsill, or was naturally clumsy. It is remarkable, even accounting for the low quality of police reports in general, how little the three officer's statements agreed with each other. Anarchists showed up en masse by the police headquarters, according to Lanza, who also overheard a police officer say, in reference to Pinelli's death: "A dog has died, one less dog to worry about." There were arrests of all Pinelli's associates, but they were swiftly released.

Milanese anarchists organized and on December 17th, issued a press statement that was carried by several newspapers. It was simple and to the point, according to Lanza it read: "“Pinelli was killed, Valpreda is innocent and the massacre is the State’s doing.”

The Italian press also was deeply skeptical about the circumstances of the Piazza Fontana bombing, Pinelli's death and Valpreda's detention, and about the competence of the Italian Police force. Corriere della Sera wrote, according to Lanza:

“Between the attacks on 25 April, in August and last Friday, there is a connection: a logical continuity the underside of which is a government and police conspiracy targeting the anarchists. The dead of the Piazza Fontana are to be chalked up to the ‘sixth sense’ of the police that jails innocents and leaves the guilty parties operating, undisturbed, ‘beyond the law’. Guilty parties for whom the Ministry of the Interior covers up but into whom inquiries should be mounted.”

The Milanese police had just lit a match and thrown it, figuratively, onto a collection of gasoline cans. Killing Pinelli was just about the worst thing they could have done. Pinelli's death marked another point of escalation in the years of lead. It gave all Italian non-fascists a rallying point, a discrete incident to point at and say: "Yeah, that, we're against that."

Pinelli lived on in surprising ways after his death. The playwright Dario Fo wrote a play inspired by Pinelli's unjust fate, unsurprisingly called The Accidental Death of an Anarchist.

Songs were written about him, the most famous of which (translated into English) read as follows:

That evening it was hot in Milan

how hot, how hot it was,

"Brigadiere, open the window!",

a push ... and Pinelli goes down.

"Mr. questor, I told you already,

I am repeating that I am innocent,

anarchy does not mean bombs,

but equality in liberty".

"No more humbug, confess, Pinelli,

your friend Valpreda talked,

he is the author of this bombing,

and you certainly are the accomplice".

"Impossible!", shouts Pinelli,

"A comrade couldn't possibly do that

and the author of this crime,

must be sought among the masters".

"Watch out, suspect Pinelli,

this room is already full of smoke,

if you persist, we'll open the window,

four floors are hard to do".

There's a coffin and 3,000 comrades,

we were clasping our flags,

that night we swore,

it won't end this way.

And you Guida, you Calabresi,

if a comrade was killed,

to cover a State slaughter,

this fight will just get harder.

That evening it was hot in Milan

how hot, how hot it was,

"Brigadiere, open the window!",

a push ... and Pinelli goes down.

Thousands of people showed up for Pinelli's funeral in Milan. Valpreda was in custody, soon to be moved out of Milan and would remain in jail for decades. The message of the police, the fascists and the Italian State was clear, not a declaration of war against the working people of Italy, but a declaration of impunity.

Suffice to say, that Pinelli's death did not go unnoticed, nor did the 'accidental nature of his death' story wash with the public in the slightest, especially in the anarchist community. This was only the beginning of the ani di piombo or 'years of lead' in Italy.

Pinelli's death left wide ripples on the other side as well. One of the officers accused (certainly the highest ranking) was Luigi Calabresi, who was tried and acquitted of involvement in Pinelli's murder several times.

Given the Milanese police force's reputation for corruption, dishonesty and hostility towards anarchists in particular, this ruling didn't exactly create confidence in the Italian public. Anarchist publications and activists (most notably Lotta Continua) kept Calabresi a nervous wreck until his death in 1972 (the Byzantine series of arrests, acquittals and re-convictions of the suspects in the Calabresi case is a subject for another time).

If somehow you need proof of the deeply entrenched fascist element in Italian political culture, consider that Calabresi is considered a martyr by the order of Pope Paul VI and in 2004 the president of Italy posthumously awarded Calabresi the gold medal for civil merit.They might as well have stapled a medal on a dog turd.

The death of Pinelli and the bombing of the Piazza Fontana also had a lasting effect on the developing school of insurrectionary anarchism.

Alfredo M. Bonanno, one of the luminaries of that school of thought, wrote in his essay, Armed Joy, arguing that the "Hot Autumn" of 68-69 didn't go far enough and made the fatal mistake of playing a rigged game by capital's rules:

"Every now and then politics come to the fore. Capital often invents ingenious solutions. Then social peace hits us. The silence of the graveyard. The illusion spreads to such an extent that the spectacle absorbs nearly all the available forces. Not a sound. Then the defects and monotony of the mis-en-scene. The curtain rises on unforeseen situations. The capitalist machinery begins to falter. Revolutionary involvement is rediscovered. It happened in ’68. Everybody’s eyes nearly fell out of their sockets. Everyone extremely ferocious. Leaflets everywhere. Mountains of leaflets and pamphlets and papers and books. Old ideological differences lined up like tin soldiers. Even the anarchists rediscovered themselves. And they did so historically, according to the needs of the moment. Everyone was quite dull-witted. The anarchists too. Some people woke up from their spectacular slumber and, looking around for space and air to breathe, seeing anarchists said to themselves, At last! Here’s who I want to be with. They soon realized their mistake. Things did not go as they should have done in that direction either. There too, stupidity and spectacle. And so they ran away. They closed up in themselves. They fell apart. Accepted capital’s game. And if they didn’t accept it they were banished, also by the anarchists.

The machinery of ’68 produced the best civil servants of the new techno-bureaucratic State. But it also produced its antibodies. The process of the quantitative illusion became evident. On the one hand it received fresh lymph to build a new view of the commodity spectacle, on the other there was a flaw."

I don't necessarily agree or disagree with Bonanno's point here (who is worth reading, because of, not despite, his fiery and moving rhetoric), but simply noting that the late sixties produced a sea change in political involvement in Italian politics, how one conceives of resistance to a fascist state, and the literature of world anarchism.

The strategy of tension failed in a macro-sense because people got involved and pushed back against the State's efforts collectively and individually and at times violently. By 1990, the cat was out of the bag for the neo-fascists as the people funding their efforts were revealed. While Italy is certainly no utopia now, at least some progress has been made from the late 60s.

This period in history has many lessons for us now, as our own American police forces protect and encourage fascist violence while cracking down on protests for a living wage, racial and environmental justice, and human rights.

There is a lot to do: join your local mutual aid society. Volunteer your time, your expertise, your passion for there is always someone in need. Give money to bail relief funds and food-banks. Build communities and dialogue. Mobilize and work for a better world with your comrades.

Perhaps the most important work is to imagine a better world, one without the specter of coercive power, and then share it.