At least you aren't Captain Oswald Bastable, air-pilot and toy of multiple parallel universes with a shady past and uncertain future(s). That guy, the protagonist of Moorcock's The Steel Tsar never gets a break, as he slips through parallel worlds, seeing endless permutations of 20th century history play out against a consistent background of nuclear anxiety, airship-battles and alternate endings. And to top it all off, this is one of the earliest popular examples of the steam-punk genre!

Bastable's starting reality is different from ours. It is a world where the 1905 Russian revolution (in the original timeline) succeeded nearly bloodlessly and the Kerensky government managed to avoid the major pitfalls of early 20th century Russia. Which is to say, much needed reforms, stayed out of WWI, made a parliamentary democracy with a sort-of social welfare net.

Then WWII happened.

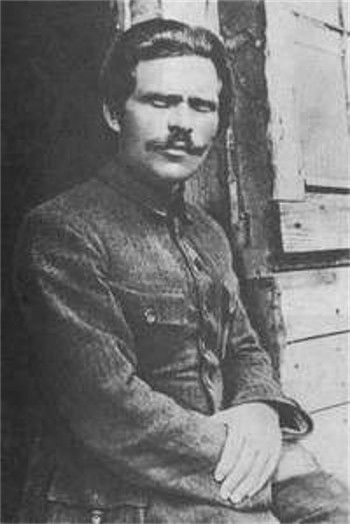

This is the Russia that Bastable is familiar with, and so is shocked to see so dramatically changed in this particular timeline where the book opens as a stranger in it. But while the redoubtable (and for some reason I imagine him as mustachio'd) Bastable may be the protagonist of the series, he is not the focus of this blog. Nestor Ivanovich Makhno--but not as he lived in our world--is that focus.

Makhno was an anarchist, rebel leader against the White and Red army during the Russian Civil War, and a tremendously complicated fellow in any timeline. We're going to talk about how Moorcock's Makhno differs from--and harmonizes with--the Makhno in our timeline in essentials despite being in vastly different positions.

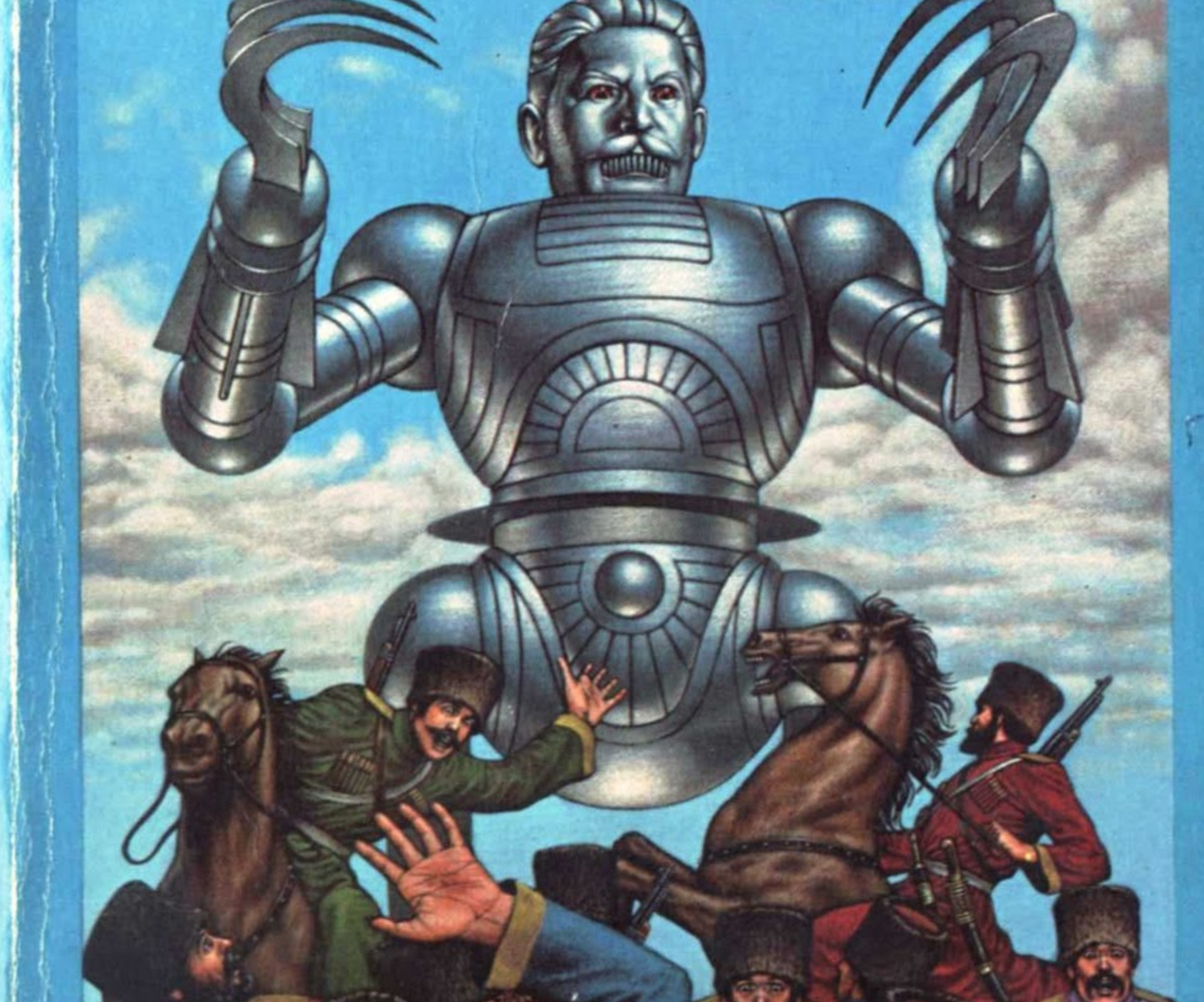

Moorcock's Makhno is first encountered in a Japanese POW camp in the 1940s by the ever drifting Bastable. Nestor Makhno goes from a throwaway character to a driving force in the novel about half-way through the text--striking up an uneasy alliance with Joseph Stalin (called by his mile-long birthname, Josef Djugashvili) and an assembly of cossacks against the consolidating and nominally democratic government of Kerenski in Moscow, which doesn't think much of Nestor Makhno's idea of a directly democratic anarchist Ukraine.

Stalin, of course, being Stalin, has about as much use for democracy as a rhino has for a gossamer dress. The principal antagonist of the book, Stalin alternately tries to extend his temporary alliance with Makhno, have the anarchist assassinated, and indulge in war-crimes.

Throw in three out-of-sync time-travelers into the mix of cossacks, double-crosses and suspiciously triggered nukes, and you have a hell of a ride. I daren't say more for fear of spoilers. Anyway, onto the main thrust of this blog.

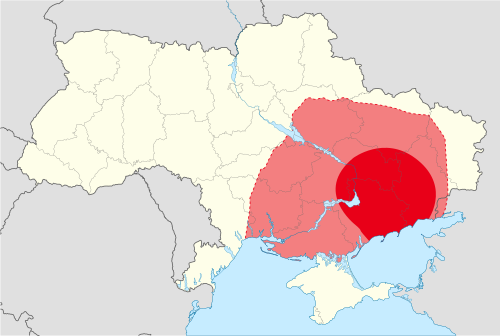

Moorcock's Makhno is an interesting figure. The Black Army and Ukrainian Free territory spreads differently in this timeline: more condensed, focused on the Cossack/military aspect rather than the conflicts between factions of Austro-Hungarians, Germans, Mennonites, Jews, White Army, Black Army and Red Army that dominated our worlds' Russian Civil War.

Part of this is doubtless due to space constraints--whole libraries have been written about the Makhnovschina in all its aspects--social organization, military, communications, notable leaders other than Makhno, the list topics and sub-topics is endless. Instead of diving into this--Moorcock chooses to make his alternate timeline largely sidestep those groups and focus on Makhno's affinity with recruiting Cossacks of the Ukraine--horsemen with a checkered history of both brutality and rough democracy. The Steel Tsar is fundamentally a war-story, with the focus on battles, intrigue and the ethics of using nukes in a world that doesn't know about their after-effects.

Moorcock's Makhno is largely solitary--he's the lone speaker for the philosophy of anarchism in this world. Major anarchist players of the era from our reality like Maria Nikiforova and Fedir Shchus are nowhere to be seen in the battlefields of 1940s Ukraine. In this particular timeline, Makhno is the primary speaker for anarchism, specifically anarcho-communism in the Ukraine. It is a burden that Makhno as a character is written to handle adroitly--and he uses actual anarchist praxis (governing his Black Army by consensus--direct democracy--rather than by fiat or coercion).

In this version of the Free Territory (also called, by people who really ought to have known better, Makhnovia), there is no Silbertal Massacre, no Eichenfeld Massacre, no Kontrrazvedka enforcing terror on civilians, Chekists and counter-revolutionaries alike. The Steel Tsar has is no hidden war of assassination and counter-assassinations that characterized a lot of the 'behind the scenes' action of the Russian Civil war in our timeline that went on for years even after the civil war officially ended.

There are nods to the cloak-and-dagger aspect of combat, though– in one case, late in the book, Stalin tries to have Makhno shot before he can leave their shared camp. Makhno replies to this provocation by shooting his assailants, bursting back through the tent flaps and telling the would-be-dictator he'll have to do better than that before leaving. Stalin says that Makhno will come to nothing, and he will become the Steel Tsar and rule Russia with an iron fist.

The world of The Steel Tsar is a world of fantasy, because this violent rebellion is not accompanied by the crimes of expediency that tainted every major player in the Russian Civil War. Moorcock's alternate world allows for a cleaner, idealized form of revolution that fits the stakes he's established, but would be out of place in our history.

I mean this is a good thing. Our timeline might be horrible, but at least we never had a killer-robot in the shape of Stalin wreaking havoc through a battlefield.

Makhno is a stubborn idealist in Moorcock's world. Moorcock gives Makhno some of the best lines in the text:

"We must live by example and offer example to others," said Makhno. "It is the only way."

And:

"Only when we accept responsibility for our own actions do we become free. And only when every one of us accepts their share of responsibility will the world become safe for us all. Lobkowitz tells us this. Dempsey [one of the time-travelers] destroyed himself because of it. Sometimes, as you say, Mrs. Persson, we must re-examine our ideas--look carefully at what 'honor' means for example."

The last lines that Makhno speaks in the text are particularly worth quoting in full:

"Violence creates nothing but violence, no matter what we call it and what the excuses. And so it goes down all the centuries. Our experiment will show that this is not necessary. We shall be a guiding light for the people of the next century."

'He began to hum some old Ukrainian melody...eventually, the anarchist stumbled away, genially waving to us almost by way of blessing."

All in all, Moorcock's Makhno, when boiled down to his essence, is what Makhno might have been in another world. Instead of dying in squalor in Paris in 1934, the anarchist free-state of what was once Ukraine, is allowed to grow and thrive--to show the world a better way to order itself, a world, to paraphrase our timeline's Makhno: "Power itself is be abolished in order for humankind to be free."

Speaking of excellent works on Makhno, there is an excellent talk on the subject hosted by none other than the redoubtable Sean Patterson, hosted an interview on UkeTube: