These are five minute episodes (ok, 5ish minute episodes) covering topics not strictly related to the office of the doge in my limited rundown of Venetian history.

And because I talk a lot, the blog space under the video will be the things I couldn't even fit into the video proper (and lists my sources).

Anyway, lets get onto the topic at hand!

Corpse-theft!

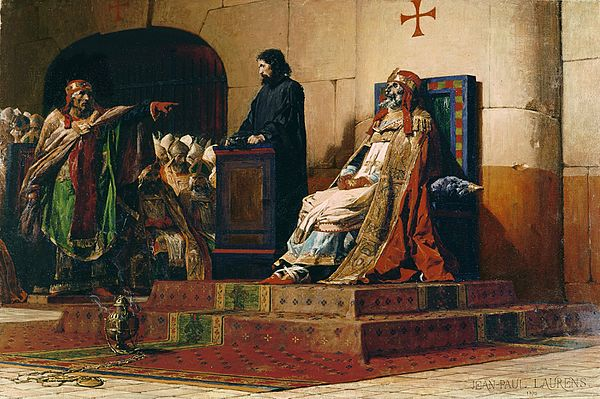

You can do a lot of things with corpses. Put them on trial, for one thing. I'm looking at you, corpse of Pope Formosus, dug up and put on trial for perjury!

(The Corpse/Cadaver Synod will never NOT be something I find hilarious).

One can also steal corpses.

Don’t look so shocked, the stealing of corpses has a long, if not glorious, history. And the two most famous examples of corpse-theft that spring to mind both involve Egypt.

Perhaps the most famous example is Ptolemy gleefully boosting Alexander the Great’s preserved corpse and using the legitimacy that came from having the body of his boss to set up his own dynasty in Egypt.

If we've learned anything from these examples, it's that sometimes the body politic can be a corpse.

Like Ptolemy, the city of Venice would also contrive to steal a corpse to boost their own legitimacy, but in this case, FROM Egypt, not absconding TO Egypt. Alexandria, to be precise. Where the body of St. Mark had rested for about 700 years.

Chillin'.

On the theft of St. Mark’s body historian JJ Norwich says:

“History records no more shameless example of body-snatching; nor any—unless we include the events associated with the Resurrection—of greater long-term significance.”

In 828 AD the Venetians got their chance to upgrade their status in the eyes of the world. And all it would take to assure a significant boost was a little matter of corpse theft from Alexandria. As you may recall, the Venetians put it about that Mark had stopped by the lagoon before Venice was even a thing, been interrupted by an angel who swore that he would 100% rest on that very spot (the future city of Venice)...eventually.

JJ Norwich, in his History of Venice has this to say on the subject of political legitimacy and the overlap between politics and religion:

“If the Republic was to command respect in the new Europe that was gradually taking shape around it, it needed some special prestige beyond that which wealth or sea power alone could confer; and in the middle ages, when politics and religion were still inextricably intertwined, the presence of a an important sacred relic endowed a city with a mystique all its own. The body of St. Zacharias might be better than nothing, but it was not really enough. That of an Evangelist, on the other hand, would endow Venice with Apostolic patronage and place her on a spiritual level second only to Rome itself, with a claim to ecclesiastical autonomy…”

One successful corpse-heist later

Having transferred the odiferous saint’s body (or someone’s body, at any rate) to Venice from Alexandria, the Venetians proceeded to make all the social/political/spiritual gains they reasonably could from it. Rome might have Saint Peter, but fuck them, Venice had Saint Mark!

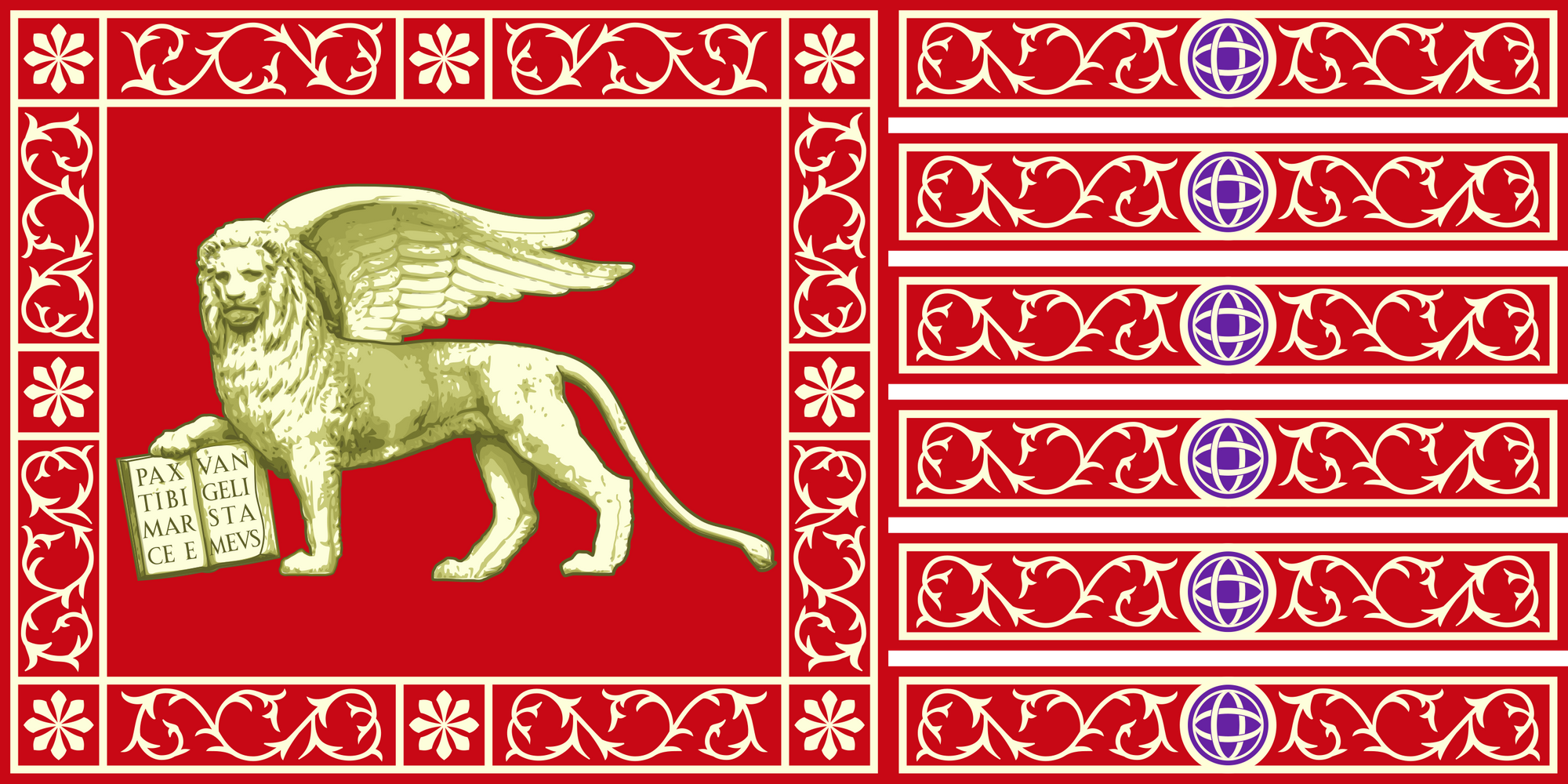

St. Mark’s sacred animal—a winged lion—was to become a symbol of city of the Republic of Venice itself and put onto every possible surface—as a sign of pride, or in the case of the Venetian territories and colonies—of Venetian ownership.

The city of Venice, even before this, had its share of lions statues and iconography, some from surprising places and times. There is one on the high column on the Piazetta that has been dated to be over 2,500 years old—of course it has moved house a few times, but the last 850 years have been spent in the service of the Venetians.

After 828 AD, there was an explosive proliferation of winged lions throughout Venice.

Historian Gary Wills in Lion City: Venice and the Religion of Empire describes going lion-watching in modern-day Venice like this:

“Wherever you turn, in Venice, lions strut or lurk, colossal or miniature, placid or menacing…one sees more accommodating lions, carved in relief on the facade of the Doge’s palace—two of them facing in opposite directions, align their backs as a throne for a personified Venice as Justice, who holds in her hands a sword and the scales of judgment…there are also lion heads between the arches all down the long colonnade of the Doge’s palace, as well as over the arches of the library facing the palace…go to the Arsenal, where Venice built its famous ships, and you find exotic lions on its front lawn—captured animals brought from Greece, kenneled here. Other lions project from the Arsenal’s gates or decorate its flagpole base…cross to the nearby island of Murano, you will find a casually sprawling lion carved in relief on a little bridge…out on the walkway near the Danieli hotel there are are monstrous lions, ten times life-size, cast in bronze. One is gnawing at chains that have bound it for a time (a cat sunning itself on the lion’s glistening back does not notice the discomfort of its oversized relative).”

But obviously, stands to reason, that the more lions of St. Marks could be found in a city, the more Venetian it was bound to be. Lions entered the Venetian language, sculpture, art, metaphor, any possible cranny of Venetian life.

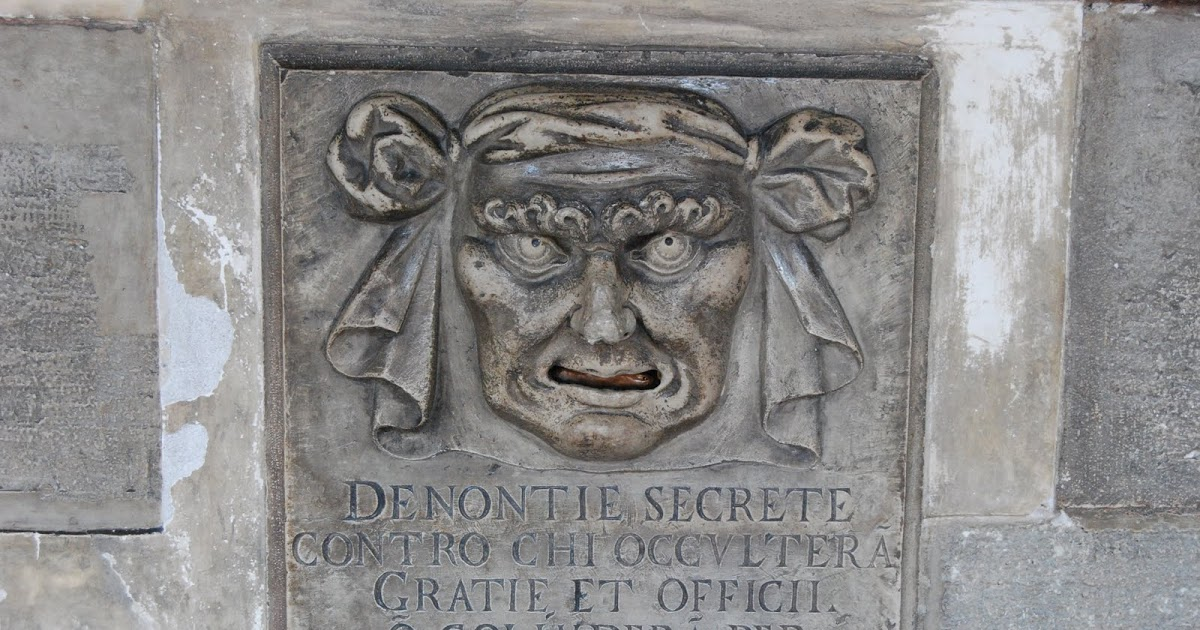

Even the anonymous boxes that the Venetian intelligence services used to collect slips of paper with the denunciations and complaints of Venetian citizens, were called bocche de leone--lion boxes. (We're gonna spend some time, later on, discussing the Venetian intelligence services and how they set expectations for state security organs going forward, don't worry).

The Lion of Saint Mark eventually became short hand for the Most Serene Republic, its embodiment.

There is a bit in most tour-guides texts or spiels on Venice that state that if the lion of Saint Mark is portrayed with an open book, the republic was at peace.

If the Republic of Venice was at war, the myth goes, the Lion of Saint Mark would either have a closed book or a sword in its paws.

As appealing a story as that may be, it remains that—appealing, and unsupported by evidence from primary historical sources. It's a nice bit of cocktail chatter, but nothing I would put much stock in.

I partially suspect that this theory ( open book=peace, sword=war) was thought up by some enterprising Venetian to sell more flags with the Lion of Saint Mark in various poses and accessories.

Saśa Iskric has a theory about the Lion of Saint Mark and it's use as a symbol (and what those symbols might mean) which is well worth your time to check out, but I won't be getting into it myself.

Speaking of which, the current coat of arms of the City of Venice is the Lion of Saint Mark crowned by the ducal corno.

The point I’m trying to make here is that the Lion of Saint Mark in some key ways IS Venice, in terms of iconography.

Next post will deal with the wearer of the corno--the other Venetian icon, the office of the Doge!