This is part one of a seven part series on the Ukrainian anarchist Nestor Ivanovich Makhno. So naturally, I'm going to start generations before he was born, examining the conditions that helped make Ukraine what it was during his lifetime. It means we're going to be dealing with, among other things, cossacks, khanates and Catherine the Great.

For a brief history of the Russia Civil War through music click here.

For my previous work on the callous and comically incompetent reign of Alexander Kolchak during the Russian Civil War in Siberia click here.

Sources:

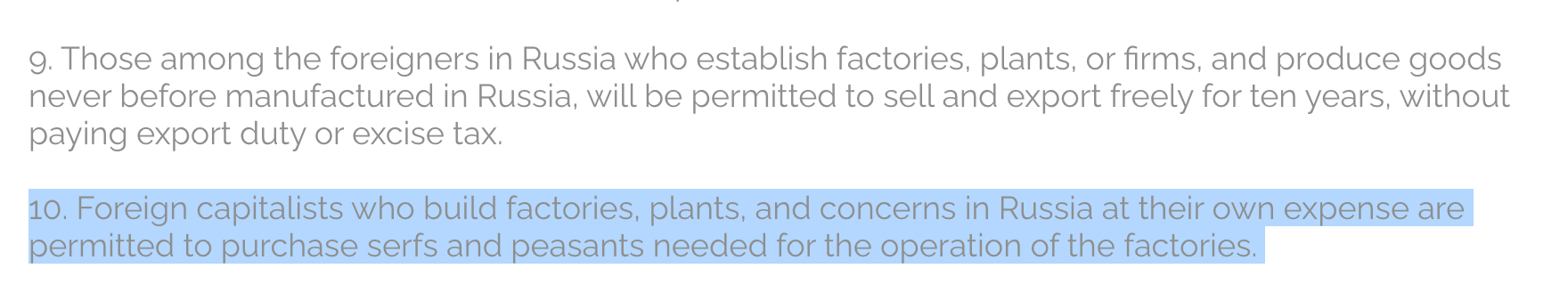

Catherine the Great's Decree (1763)

In which she promised some pretty heady things would would-be settler/investors to Russia, among them, not to put too fine a point on it, was the ability to purchase human beings.

HG WELLS OUTLINE OF HISTORY VOLUME 2. On the interactions between Cossacks and khanates. Wells is typically caustic, insightful and understated in turn, remarking of the Cossacks:

"To the west, over large tracts of open country, and more particularly in what is now known as Ukrainia, the old Scythian population, Slavs with a Mongol admixture, reverted to a similar nomadic life. These Christian nomads, the Cossacks, formed a sort of frontier screen against the Tartars, and their free and adventurous life was so attractive to the peasants of Poland and Lithuania that severe laws had to be passed to prevent a vast migration from the ploughlands to the steppes. The serf-owning landlords of Poland regarded the Cossacks with considerable hostility on this account, and war was as frequent between the Polish chivalry and the Cossacks as it was between the latter and the Tartars."

Leaving aside Wells's period-specific language, he hits at a fundamental tension in the existence of Cossacks and steppe people so closed to settled societies. People of the steppe--cossacks or Crimean raiders or any other of the Turkic tribes--didn't have to pay taxes to a tyrant and could live more or less as they pleased.

The cossacks might kill a serf who abandoned his homestead and set out to join them--but they were just as likely to allow them to join their band. This created pressure on settled cultures--if your serfs desert to live free on the steppe, soon you'll have no one to work the fields and pay taxes, and then where would you be? This created incentive for Catherine to destroy the cossacks, as serfs would desert to freedom whenever possible, and without serf-labor, there could be no Russian nobility, and nobody to support the monarchy.

Russian Rulers and History Podcasts: The Pugachev Rebellion Part 1 and The Pugachev Uprising.

A very useful podcast that covers vast amounts of Russian history. I'd say more about it, but the links above pretty much demonstrate what I mean. Go and listen to them, these episodes provide a great overview of Pugachev's uprising and how it shaped Russian social policies for generations.

Serhii Plokhy, The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. For more on Catherine the Great’s dismantling of the Cossack Hetmanate, the absorption of the Crimean Khanate, and the myth of the enlightened despot. Features the quote from cossack writer Vasily Kapnist: "You burden them, you put chains on those who praise you."

Plokhy also has a dab hand at summarizing complex events. For example:

"Three of the latter--Catherine II of Russia, Frederick II of Prussia and Joseph II of Austria--became known in history as 'enlightened despots'. In addition to being their countries' second monarchs to bear their names, as well as their belief in rational administration, absolute monarchy and their right to rule, another commonality united them: they all took part in the partitions of Poland (1772-1795), which ultimately crushed the commonwealth's Enlightenment-inspired efforts to reform itself."

The book also acknowledge's Ukraine's difficult history with anti-Semitism--as evidenced by various pogroms carried out by cossacks, Russians, religious figures and peasants looking for a scapegoat. This would continue to shape the politics, economics and history of the Ukraine for generations. In closing on this source, I beg you to consider this quote could be the summary of Ukrainian history in a nutshell (emphasis mine):

"The Catholic rebels wanted a Catholic state without Russian interference, while the orthodox wanted a Cossack state under the jurisdiction of Russia. The Jews wanted to be left alone. None of the groups got what they wanted."

Albert Seaton, The Horsemen of the Steppe: the Story of the Cossacks. Specifically on the results of Pugachev’s rebellion, integration of the cossacks into the Russian military apparatus under Catherine and Paul, massacre of Crimean Tatar population according to British sources at the time.

Most significantly, this quote:

"In 1783 Russia, on the pretext of restoring order, had occupied the Crimea and according to British reports at the time, had massacred a considerable part of the Tatar population: much of the rest fled to turkey. The last of the khans was forced to become firstly a Moscow pensioner, and then, when the promised pension was not paid, to take refuge with the Turks. In 1787, there followed another of Catherine's wars against the turks resulting from Turkish intrigues with the remnants of the Crimean Tatars and from Russian designs on Georgia and the Caucasus: by the treaty that concluded this war, concluded in 1792, Russia received Ochakov that ran on the Dniester river..."

Essentially, Russia got around the cossack host's borders by swallowing up the lands around them and recruiting them into their military apparatus. Not to mention the massacre of Muslim citizens of the Ukraine (which Massie, Catherine's biographer, largely glosses over or discounts).

Robert K. Massie: Catherine the Great: Portrait of a Woman. Most useful for the account of the Pugachev rebellion, not to mention Potemkin and the administration of the former Crimean Khanate into Russian holdings. It's where we get the phrase "Potemkin village" from. Massie is unflinching in documenting Catherine the Great ‘removing all traces of the internal revolt’—basically un-personing Pugachev. Pugachev's homestead was torched, the Cossack host he rode with being renamed from Yaik to Ural and his wife and daughters imprisoned for life.

Furthermore, Pugachev's name was forbidden to be spoken under penalty of the law of the Russian empire. Savage retaliation against the serfs by the nobility--though Pugachev survived as a folk-hero in the collective memory.

Catherine the Great gave the nobility the ability to buy serfs wholesale with the land and turned a deaf ear to her people's reports and appeals of widespread abuse.

It is worth noting that Massie goes into considerable detail in documenting the crimes of both Pugachev's host and Catherine's armies. For example, on the subject of Pugachev's depredations (which were matched by Russian troops):

"Villagers who persisted in recognizing 'the usurper, Catherine,' were hanged in rows; nearby ravines were filled with bodies. Desperate townspeople, not knowing what their interrogators wished to hear, gave stock answers when asked whom they considered their lawful sovereign: 'Whomever you represent,' they replied."

This sort of blurring of the lines between civilian and combatant was characteristic of this time period, and of the legendarily bloody Thirty Years War and the upcoming Russian Civil War. Massacres by armies (or civilian bands/militias) were horrifying for how common they were--caught in the middle, the peasants did their best to survive. Things only got worse after Catherine finished off the rebellion--she gave the nobility carte blanch to treat the serfs as they wished, since the nobility, and not the peasants, had supported her claim to the throne.

There also some hidden gems in this account--such as one regard of Catherine's generals, Panin, who at one point was tasked with putting down Pugachev. Massie says:

"She recognized Panin's military abilities but disliked him personally...Catherine worried about his reputation as a military martinet and his unconventional personal behavior: he sometimes appeared in his headquarters wearing a gray satin nightgown and a large French nightcap with pink ribbons."

Sean Patterson: Makhno and Memory: Anarchist and Mennonite Portraits of Ukraine’s Civil War. We're going to be using Patterson's excellent work a lot in this series. For this episode, the primary take-aways are focused around the Mennonite incorporation into the Ukraine peaking in the 1860s, the destruction of the Zaporizhian cossack sich prior to Mennonite arrival in 1775, featuring a quote from Catherine the Great and the reduction of free people to serfdom and vast swathes of land being given to the Russian nobility in 1783. Patterson recounts:

"Former Cossacks and peasants sometimes found themselves registered as serfs and forced to pay dues (obrok) in the form of labor, to newly settled Russian land owners. Massive land tracts were gifted to Russian nobles, who in turn imported their own estate serfs from central Russia to work the land. In this manner, the region's population of serfs rose from 1.32 percent in 1764 to 27.9 in 1781."

Additionally, the first Mennonite colonists arrive on the lower reaches of the Dnipro’s right bank set themselves apart and his chronicle of Mennonites gathering wealth and power through daughter colonies and bonding themselves tightly into the empire, though remaining culturally distinct. When the Russian empire goes down, so do Mennonite fortunes.

Detouring from Patterson for a moment:

A copy of Czar Paul's 1789-1790 invitation to the Mennonites can be summarized as follows:

1. They would be free to practice their pacifist religion (as opposed to being forced to convert to Russian orthodoxy).

2.They would have land rights over the native Ukrainians and Russians

3.Free trade

4. They would have the right to make beer vinegar and brandy (a privilege usually reserved for the Russian state).

5. Nobody could use Mennonite land unless the Mennonites said so.

6. No compulsory military or civil service.

7. They were immune from billeting troops, and forced labor for the Crown, but in return had an obligation to build roads and bridges.

The vast majority of Ukrainian Mennonites were culturally German and wealthy or at least well-off land-owners, a fact that remained true during Makhno’s childhood. The power and wealth of the Mennonites will be a rather important thing to remember as we move forward with the Nestor Makhno series.

Dr. PAUL SCHACH. Russian Wolves in Folktales and Literature of the Plains: A Question of Origins

Professor and specialist in German-diaspora language and folklore who wrote extensively on the spread of Russo-German ‘wolf stories’. That is, the by-now trope of a troika sled pursued by a wolf-pack at night, filled with panicking people, usually a wedding party. The darkest version of this story has the inhabitants of the sled throw the bride and groom over to the wolves to lighten the load—it doesn’t solve anything and the wolves eat everything anyway.

The story doesn’t originate in Mennonite or German folklore, but rather from a book Les Mysteres de la Russie in 1844, and was popular with German immigrants into the Ukraine. Schach writes:

“If as Alekseev, maintains, this attack by a French writer on the repressive political system of Russia is actually the source for the wolf tale in Browning’s poem…certainly at least a few of the German immigrants would have been eager to read a book that purported to reveal the ‘secrets’ about the politics and morality of their homeland.”

Schach’s extensively researched article provides us a fitting metaphor for the long-term effects of Catherine’s policies in the Ukraine over the long term (the fact that these tales of moonlight-sled rides and being gobbled up by wolves survived many Mennonite movements across the Atlantic to the plains of Middle America, most famously in Willa Cathers MY ANTONIA, is beyond the scope of this blog, but no less interesting for all that, even though it is the focus of Schach's work).

Catherine the Great’s policies of encouraging economic and civil rights for the wealthy at the cost of the Russian (specifically Ukrainian) peasants and serfs. If you will permit an extended metaphor: the nobility and landed aristocracy were on a sleigh-ride of prosperity, but the wolves of serfdom and change were simmering, surging after. Horses—and caste-like aristocracy—cannot run forever.

Eventually the wolves will catch the troika, no matter how many people are thrown over the side to placate them and lighten the load.

Wrap-up:

Episode two will premier on the 20th of August, and on this website (with sources!) on Friday the 21st, so if you want to be informed automatically subscribe to my mailing list below. If you have any questions or comments about this or any other post, feel free to get in touch with me.