For more work on Venice and its strange history, click here!

This is necessarily a broad topic--with a lot of points of entry and angles of analysis--but mine is going to be focused on the later days of the Venetian Republic and Ottoman Empire, along with the Mamluk Sultanate popping up here and there.

Lets get to it!

Some more things to get into before I forget them:

Venice as middleman:

As you may recall, Venice--using Venice to refer to the interests of the empire and city state rather than individual governments or doges--dearly loved being the middleman as a policy. There was a very good reason for this--when you're the middleman, you can dictate terms to your trading partners/customers--because you know the majority of them aren't going to make the journey to Asia for say, silk or tea or whatever valuable commodity you could care to mention--so they'll pay your price.

Or to put it even more simply: The Silk Road, which reached its height during the Mongol Khanates--and fragmented about the same time they did, was a major engine of Venetian trade and cultural exchange. Venice took as much advantage of this position--and their trading posts on the Caspian and Black Seas--as they could.

But, as we all know, good things don't last forever--and the splitting up of the Mongol Khanates--which began almost immediately from a historical perspective, starting with the Toluid Civil War (1260-1260) and escalating from there--is a fine example. Eventually, through a combination of central Asia not being safe for trade due to the remains of the Chaghatai--and later Temurid--khanates making trouble for their neighbors and that supply of Asian luxuries to Europe was functionally cut off.

Unless you were the Ottomans--or their later subjects, the Mamluks of Egypt, who controlled a short-cut to Asia by water. For a quick summary of this, I refer you to this video which lays out the position of the Ottoman empire re: new world.

Venice and the Ottomans:

The Venetians were an established power when the Ottomans finally finished off the Byzantine empire. The Venetians swiftly adapted to this regime change in typical fashion, by establishing a deep commercial relationship with their heavily armed neighbor. Many future doges had spent significant time in Constantinople as traders/spies--I'm thinking here of the most famous of this number, Doge Andrea Gritti.

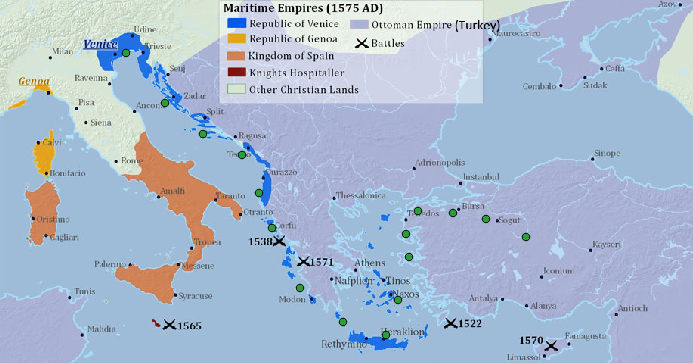

Gritti, as we've discussed, was arrested for whacky spy antics in Constantinople in his youth--and avoided execution only through his close friendship with one of the senior Ottoman viziers. This can be taken as indicative of an unusually close relationship between high-level officials of both empires--they would fight savagely over the best places to plunder (both Ottomans and Venetians would spill swimming-pools worth of blood over Greece, to the great annoyance of the Greeks, who really wished both powers would get bent) but overall were on good terms for all that.

Certainly, as the world's political and economic axis shifted west to incorporate a whole new hemisphere, both Venice and Ottoman empires remained in close contact, each viewing their capital city as the center of the world. A poem from the Ottoman seventeenth century author Nabi springs to mind:

"The heavens may turn about the earth as they will

They will find no city like Istanbul

Drawing and painting, writing and gilding

Achieve beauty and grace in Istanbul

However many different arts there may be

All find brilliance and luster in Istanbul

Because its beauty is so rare a sight

the sea has clasped it in a tight embrace

All the arts and all the crafts

Find honor and glory in Istanbul."

Doubtless, a Venetian would have written the same about Venice, and there are simply too many poems and elegy's to Venice's unique glory and elegance to start naming them. I will quote Italo Calvino's character of Marco Polo in his classic work, Invisible Cities which while written in the twentieth century, has a similar feel to it. Marco Polo is entertaining Kublai Khan with stories of his travels, and eventually the Khan asks exasperatedly if the Venetian is just making up cities since some of the cities are clearly impossible: cities of the dead, of the air, of water. Polo replies: "Every time I tell of a city, I am saying something about Venice."

Piri Reis: Ottoman Admiral, scholar, cartographer

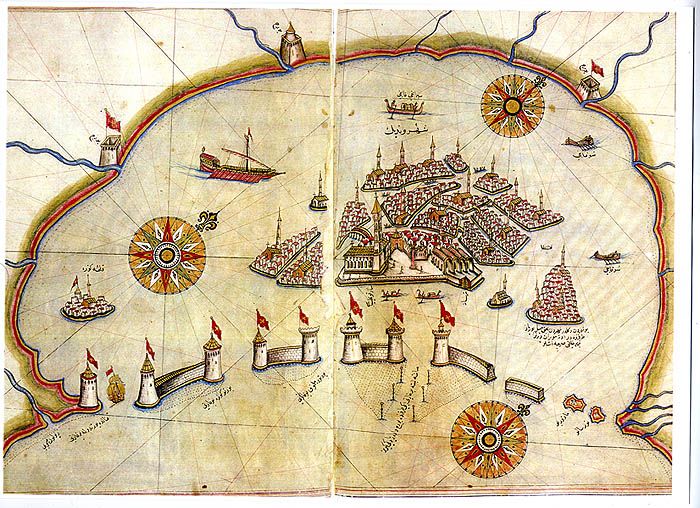

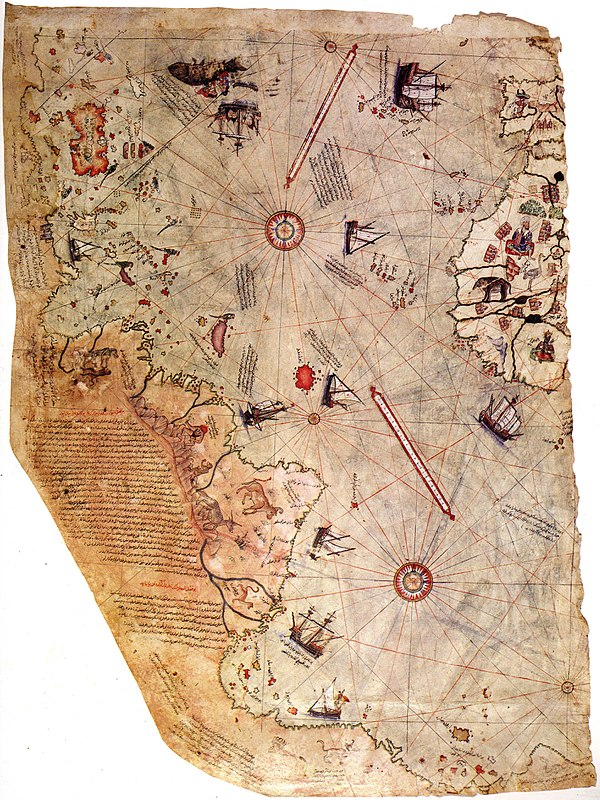

Ahmed Muhiddin Piri is the man responsible for the map of Venice that graces the top of this page. A Gallipolian by birth, his life was studded with accomplishments. The one he is best known for, of course, is the gazelle-skin map of the world including the new hemisphere--specifically, the coast of South America and the Caribbean.

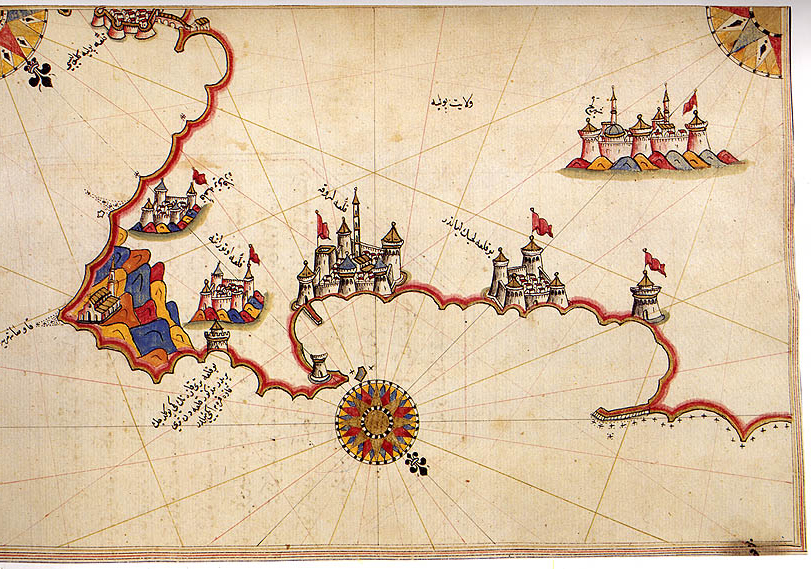

Piri also did excellent maps of Otranto, along with north African coasts and the island of Corsica. The notable admiral had experience in the Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, and Straits of Gibraltar, making him exceptionally well travelled even by Ottoman standards. You could see the whole reach of the Ottoman empire in the admiral's log-books and maps--it was a formidable--and lucrative empire, one that Venice was well advised to remain close to.

The Mamluks of Egypt eventually denied European powers access to the shortcut around the now-disintegrated Silk Road (a move that prompted the European powers to 'discover' the new hemisphere as a result, ironically) but Venice stayed in the good graces of the Ottoman empire.

Piri Reis's travel records and reach can be seen as a good embodiment of the logic that led Venice to stick closer to home. The Venetians were conservative in this regard: why be eager to extend la Serenissima to the new world--why would it take that risk when it could just trade with the Ottomans, which the other European powers now largely refused to do?

In Conclusion:

So much of Venice's trade, political leverage and culture came from their proximity to thriving and vibrant Islamic powers. While Venice was and is a unique polity, it unquestionably benefitted culturally and materially from its Islamic neighbors than it lost for them, and made it a truly cosmopolitan place compared even to other Italian city states at the time.