In which we cover some of the (mis)adventures and investments of Andrea Barbarigo, who had up until we meet him, had just about the worst luck imaginable.

If you want to catch up on the (limited) Venetian history I've covered so far, feel free to go here!

Some Things I didn't Get to Mention in the Video re: Andrea Barbarigo

In these intermezzos, I don't always have the time to get into all that I would like to get into. Andrea Barbarigo's history--and a few corrections. Storytelling is fueled as much by enthusiasm as sources, and sometimes it can overpower its bookish partner and compel me to leave things out or misspeak.

So, a few things on Andrea Barbarigo:

1) He started his career with quite an albatross around his neck.

To put it mildly, Nicolo Barbarigo, Andrea's father, had flown too close to the sun. To borrow the words of Colin Thubron in his work The Venetians:

"This [1417] journey [commanding the critical Galley of Alexandria] was Nicolo's undoing...as his fleet emerged into the open sea near Zara it was hit by storm. One of his galleys, laden with ran aground on the little island of Ulbo. Barbarigo was sailing only two galley lengths away, but he seemed to have feared for the safety of the rest of the fleet, or simply to have panicked. Ignoring distress flares from the wrecked ship he sailed on to Venice. There he was arraigned for dereliction of duty and inhumanity and was fined 10,000 ducats--a crushing sum."

This put the Barbarigo family in serious trouble, and young Andrea had to start hustling mere months after this blow. He went into the trading business, learned the ropes as best he could and tried to restore his family name as best he could. He checked off all the items on the 'Bootstrap Narrative Checklist'. It is the fact that Barbarigo was a strenous note-taker, and we know this much about him because his sales books were preserved and can be scrutinized that we have such thorough picture of the man, and this particular incident.

2) Andrea Barbarigo's Calculated Risk

In 1430--after more than a decade of scrimping and saving and backroom deals, Andrea finally has climbed back to, if not security, then to a place, where if he invests in the right cargo at the right time, at least a place were profitability could be reached. Trade could be conducted from Venice in one of two ways: through independent outfits (usually citizens who pooled their resources together to hire a captain and ship to transport and a trader to sell their wares in distant lands, a structure that is remarkably similar to a modern day corporation--essentially a profit-sharing enterprise) or through the Venetian Galleys.

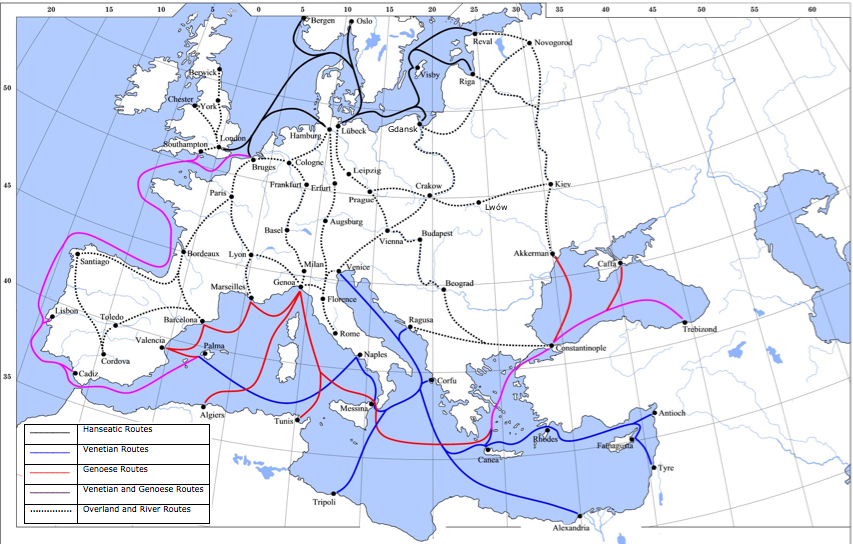

The Venetian galleys were state run and financed trade routes that went as far north England and as far East as Trebizond and the Crimea in the Black Sea. Merchants could use the same profit-sharing structure to get their goods on these heavily armed and professional fleets, which of course Barbarigo did--storing a load of pepper--a profitable commodity on a ship in the Galley of Flanders.

But just because the Venetians had this absolutely expansive trade route, didn't mean they were alone on the seas. Far from it. There were numerous other factions that might think about attacking the Venetians en-route, to say nothing of incompetence, the elements and simple misunderstandings that could all end with a loss of profit and a sunken ship.

So, like any good merchant or investor Andrea Barbarigo tried to mitigate his risks. He sent his miscellaneous goods on ahead onboard an independent outfit--a small fleet of five ships, so if a storm or pirates or battle or simple bad luck compromised one fleet, the other wouldn't be effected. After that, he had no choice but to sit back and wait in Venice.

3) Fucking Genoa

The first, independent fleet came to grief. Four of the vessels reached their destination, but one did not.

Three guesses as to why the fleet was one short.

The Genoese, unfortunately, picked off the ship with Andrea Barbarigo's merchandise aboard. Such piracy and low-key hostility was the rule rather than the exception between the two (rival) merchant republics.

I like to imagine Andrea Barbarigo absolutely shredding his fingernails with anxiety after getting this little bit of news. Why, he must have thought, why oh why couldn't those god-foresaken Genoese taken literally ANY of the other vessels but the one with his stuff on it? He hadn't even insured his goods.

4) Success

Ultimately, things worked out for Andrea Barbarigo--the Galleys of Flanders returned with the merchandise that the pepper had bought and he made a tidy profit--enough to set up his family as respectable again.

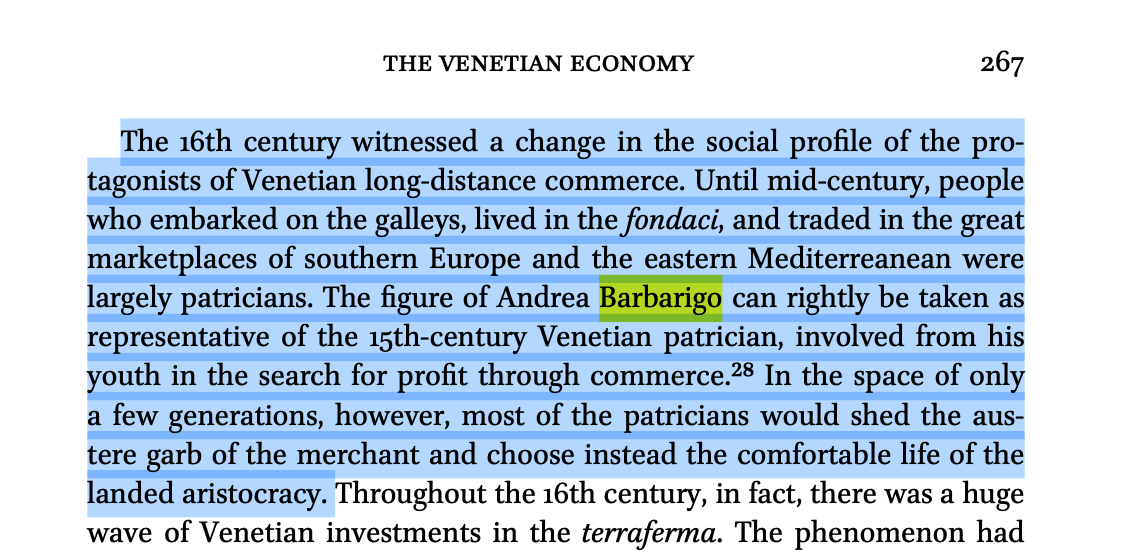

It was this sort of high-risk, high-reward investment that provided any sort of upwards social or economic mobility in the post-serrata Venice. At this point, Venice is a fully fledged oligarchy.

As Luciano Pezzolo notes, the focus for the Venetian upper class--merchant, nobili, whatever--was to pivot to owning more land on the terra-firma, to emulate their peers on the Italian peninsula with sprawling estates and lands.

This ostentatious expansion was also justified by a military necessity--the Venetians were terrified, historically, of being invaded from the landwards side, instead of from the lagoon.

So, like many empires, they expanded in 'pre-emptive self defense' to create a bubble of territory to insulate their capital from consequences. This stretch of land was often in flux, but in the centuries to come it would include cities like Verona, Padua and Ravenna among their numbers.

This matters because the Venetian terrafirma would become one of many battlegrounds during the Italian Wars and a source of major contention, which we will discuss in part tomorrow!