If you want to get some context about what's happened so far in this severely limited history of Venice, click here!

Lets open with historian JJ Norwich's description of Doge Andrea Gritti in his History of Venice:

"...Andrea Gritti was considerably more impressive a figure. Tall and outstandingly handsome, he carried his sixty-eight years lightly and boasted that he had never suffered a day's illness in all his life. As a young man he had accompanied his grandfather on diplomatic missions to England, France and Spain, whose languages he spoke fluently, together with Latin, Greek and Turkish.

This last accomplishment was the fruit of a prolonged stay in Constantinople during which he was arrested on a well-founded charge of espionage and imprisoned, escaping impalement only through the good offices of the vizir Ahmed, a personal friend. He is said, nonetheless, to be unusually popular with the Turks as well as with the European colony, several members of which were seen standing in tearful vigil by the prison gates as he entered them.

Later he had served with distinction both as a diplomat and--in a civil capacity--in the war of the League of Cambrai, and he was indeed proveditor of the army when, on May 20th 1523 he was elected Doge.

Perhaps surprisingly in view of his record, he never managed to endear himself to the people as a whole, who had hoped fro the election of his principal rival...neither then nor later, however, did his lack of popular appeal occasion him the slightest concern."

A Brief Discussion of the League of Cambrai and Pope Julius II's Eternal Temper:

To talk about Doge Andrea Gritti’s military policy, we’ll need to take a brief digression into the life of another angry, authoritarian elderly Italian man: Pope Julius II.

Pope Julius II (born Giuliano Della Rovere and hailing from Liguria) was a piece of work. I’ll make no bones about it, he’s one of my favorite historical characters simply because of how outrageously stubborn he was.

The man powered through multiple illnesses and sieges simply on the power of spite. A source I don’t particularly trust claims that he carried a stick with him at all times, so that he could use it to hit people who disagreed with him. That seems far-fetched in the super-touchy politics of Renaissance Italy, but all sources on Julius II (I’m leaning most on Christine Shaw’s biography of him and very much recommend it) agree that he had a truly volcanic temper. Nobody wanted to deliver bad news to the Pope because he would throw any and anything at the messenger, upend tables and smash whatever came to hand.

A short list of things that Pope Julius II absolutely loathed:

1) Venice (as a Ligurian—part of greater Genoa, this is only to be expected).

2) Spain. All of it. Everyone from there. Made complicated by the fact that Spain was currently occupying Naples at the time of his ascension (1503), which was pretty much the entire bottom half of Italy.

3) The Borgia family, partly because they were from Spain and partly because they kept getting in the way of his ambitions. Julius II’s outfoxing of Cesare Borgia upon Rodrigo Borgia’s death was a work of art and subtlety, or at least, more subtlety than one might have expected from such an angry man. In short order Julius II deprived his greatest rival of liberty, funds and political power, leaving him to die a painful death in Spain.

4)Julius II also hated the French, despite (or perhaps because of) the large amount of time he’d spent as an envoy to France during his time as a cardinal. He thought they were untrustworthy, and he should know.

5) He also hated that the Venetians had taken some towns in the Romagnol during the late Borgia papacy and his early days as pope, when he was short of funds and political leverage. He wanted those towns back, and now that he’d gotten the necessary funds to pay troops, he meant to do something about it.

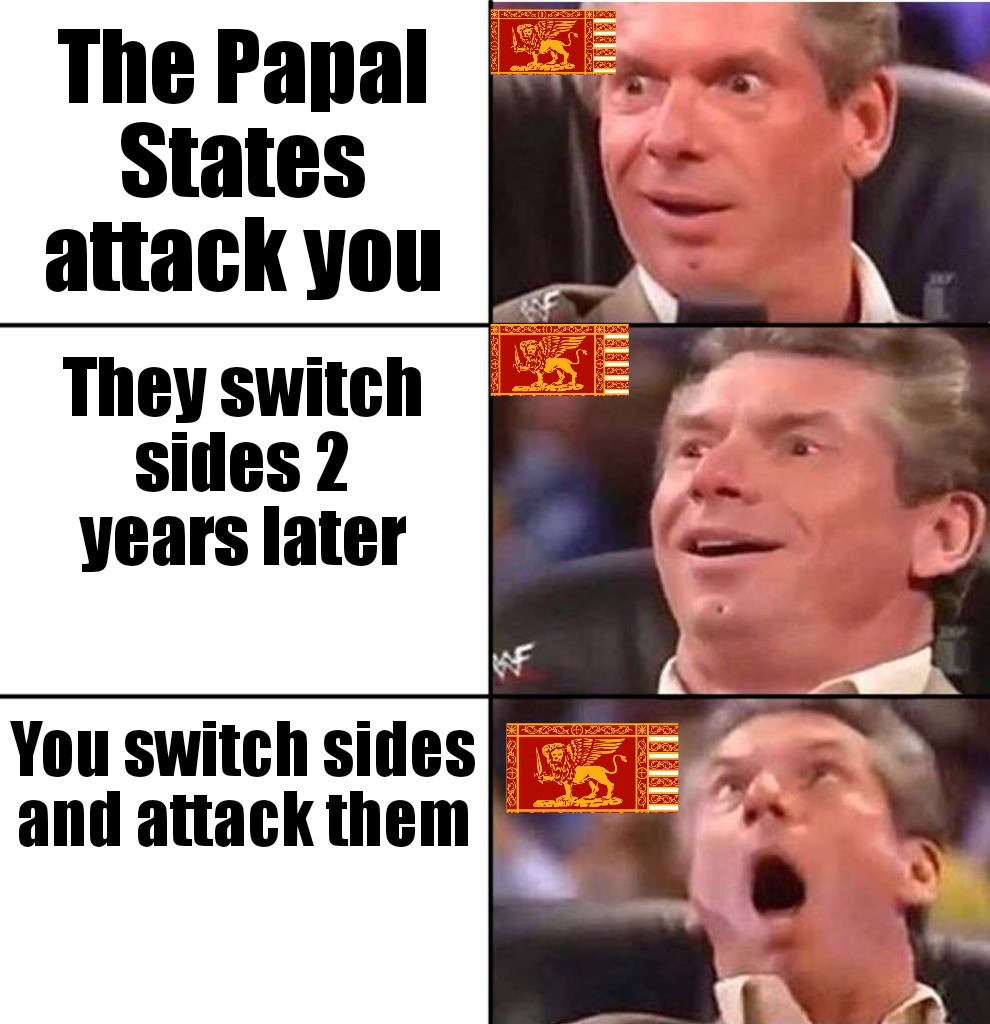

6) I’m also certain that he hated having to join the League of Cambrai—think of it as a huge anti-Venice league made of every major player in the area—but noticeably France. France had the best standing army at this time, with Spain close behind and Julius knew he couldn't win a fight against the Republic with his own forces alone.

7) This means that Venice gets utterly stomped on by the League of Cambrai—their empire of the terrafirma gets rolled up like a carpet. What had taken a hundred years for the Republic of Venice to gain, to paraphrase Christine Shaw, it lost in three weeks.

8) Julius got his Romagnol towns back, Venice has been checked, so naturally you’d think he would be happy. He wasn’t. He feared that France was too strong and so of course, he made a separate deal with Venice and switched sides, forming an ANTI-FRANCE league to diminish their influence in northern Italy.

9) It goes on like this for quite some time with betrayal and counter-betrayal until Julius II’s death in 1513.

Back to Gritti.

The reason why I get so into the League of Cambrai is that Andrea Gritti was on the front-lines of that Papal push (on the Venetian side) and it deeply influenced his behavior when he was installed as doge in 1523.

He’d seen first hand how tenuous Venice’s hold over cities in the terrafirma like Padua were—if Venice was to have any sort of hope of maintaining this buffer against the major powers of the day, they would need to completely rethink their approach to empire on land.

The Venetians would need to stop thinking about acquiring more cities in this part of the world—cities that were swiftly taken would be swiftly lost—and focus more on stability and avoiding conflicts with other Italian and European powers as much as possible. Robert Findlay calls the defeats and reverses suffered in the League of Cambrai a kind of trauma for the Venetians, who had long considered themselves superior to their neighbors in all significant respects.

Gritti knew if Venice was to have any sort of hope of maintaining this buffer against the major powers of the day, they would need to completely rethink their approach to empire on land.

Gritti’s priorities upon becoming doge were clear. End Venice’s involvement in the Italian Wars without giving up too much territory and do in such a way that wouldn’t endanger the Republic’s stability. To the shock of the oligarchy, Gritti managed this with relative ease three months after taking power, signing a treaty at Worms to this effect.

Not that Gritti was universally beloved or anything like that. He was Julius II's equal in pugnacity, caprice and volatility. He wanted to get more power for himself, and frequently feuded with the various committees that made up the Venetian government. What he had that the (by now dead) pope didn't, was a coherent and consistent plan. Under Gritti, Venice engaged a truly intimidating army and spent lavishly on defense, but with the object being to avoid war, rather than provoke it. This counter-intuitive position was reminiscent of the Roman general Fabius during the second Punic war, who refused to fight the superior army of Hannibal Barca in the field and sought to wear out his opponent through feints and delaying tactics, a comparison that was not lost on Gritti during his lifetime.

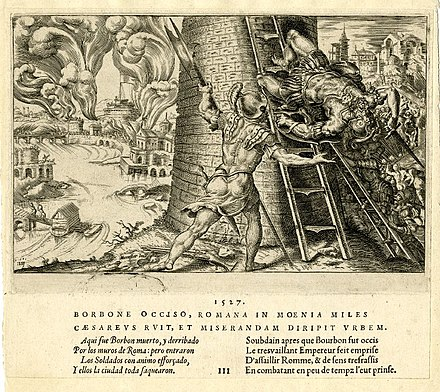

The high point of this policy was the 1527 sack of Rome which occurred with Venetian connivance despite being the nominal ally of Rome. The giant Venetian army mentioned above (ironically, under the command of Julius II's thoroughly unlikeable nephew, Francesco Maria Della Rovere I) simply dawdled outside Rome instead of responding to the increasingly panicked message from Pope Clement as the city was plundered around him.

There was some pretext or other about not wanting to move the army out of position in case someone attacked Venice, which was just that, a pretext.

Gritti's cynical foreign policy towards his one-time ally was realized at last--Venice was safe, largely because Rome was richer, vulnerable to attack, and easier to reach than Venice. It would be impressive if it hadn't come at a staggering cost in human lives and a shit ton of stolen art (something of a theme in this series).

Gritti's final years had him turning away from the Italian peninsula and worrying more about the Ottoman empire--which meant ramping up Venice's already formidable fleet. He shuffled off the mortal coil in 1537, in the middle of the Third Cretan war--but this is not the last we will hear from the Ottomans, not by a long shot.

Link to the Talkback:

https://www.facebook.com/Sewerratsproductions/videos/939808323497043/?t=2